Quakers in the Civil Rights Movement: Stories of Peaceful Persistence

Quakers have a long history of peacefully fighting for racial equality, and there is a lot to explore about their work during the Civil Rights Movement.

In this episode, we share first-hand stories of Friends whose spiritual courage led them into the heart of the movement, even when they were beaten and threatened with death. Quakers were among the most influential advocates of nonviolent direct action, choosing boycotts and sit-ins over fists and guns.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Today, we explore their work and how it affected one of the most important eras in American history.

Leave a comment below to share your stories and thoughts!

Download the transcript and discussion questions.

Discussion Questions

- David Hartsough was threatened with death when he attended a sit-in at a whites-only lunch counter. His nonviolent training and convictions gave him the strength to respond with peace when threatened. How might you prepare yourself to answer hate with love?

- Quakers who were active in the Civil Rights Movement followed different paths. What method of resistance most resonated with you? How is the Spirit leading you to respond to injustice today?

David Hartsough

I heard a guy come up from behind me and he said, if you don’t get out of the store in two seconds, I’m gonna stab this through your heart. I looked at him in the eyes and his eyes were filled with hatred. And in his hand was a switchblade. I had two seconds to decide, do I really believe in nonviolence?

Various

Thee Quaker Podcast. Story, spirit, sound.

Georgia Sparling

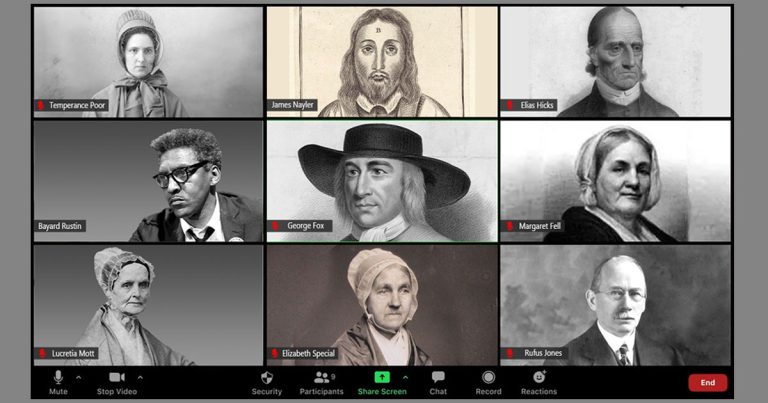

I’m Georgia Sparling and today we’re starting the first of a two-part series on the Civil Rights Movement. Next week we’re devoting our whole episode to Civil Rights leader and organizer Bayard Rustin, whose face you might have noticed on our logo for this season. But today, we’re beginning with a broader look at what Quakers were doing during the movement and by broader, I want to just say right here that I don’t mean comprehensive.

In the process of researching this show, I discovered just how impossible that would be for a few reasons. One, this show is only about a half hour. And two, there is not as much scholarship out there on this topic as you might think, but what I have learned is that there are many amazing stories of courage and conviction, from people who stood against the Ku Klux Klan to Friends who pushed for equality more quietly but no less effectively, behind the scenes.

I’m really excited to share those with you today.

I promise that we’re going to hear from those people soon, but first, I’m going to give a crash course on the Civil Rights Movement.

We all probably know that the United States has had a long and awful history of racial inequality and violence against Black people. In the 1950s, after years of smaller efforts to end unjust laws against African Americans, there came a boiling point.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. the Board of Education, that separate yet equal education was unconstitutional and that schools could not be segregated any longer.

The next year, Rosa Parks in Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white person.

Rosa Parks

Two policemen came on the bus and one asked me if the driver had told me to stand and I said yes. And he wanted to know why I didn’t stand, and I told him I didn’t think I should have to stand up. And then I asked him, why did they push us around? And he said, and I quote him, “I don’t know, but the law is the law and you are under arrest.” And with that, I got off the bus, under arrest. And with that, I got off the bus

Georgia

That act of defiance launched a citywide boycott of the bus system by African Americans with other cities following suit. This led to the legislation to desegregation of public buses and also brought Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. into the public eye and led to the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference or SCLC to support the ongoing work to give Black Americans equal rights.

About six years later in 1960, the nation saw of wave of sit-ins staged by Black students at whites-only lunch counters which eventually led to the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, more commonly called SNCC.

Pressure mounted for Washington to take action and in 1963, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom really pushed the envelope.

Martin Luther King Jr.

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Georgia

More than 200,000 people showed up to the event, which was largely organized by Quaker Bayard Rustin, and in which King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. It may be familiar to you.

Martin Luther King

Cause I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the color of their skin but by the content. I have a dream today.

Georgia

The following year, the president signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, barring discrimination based on race, color, religion, or national origin in public facilities. The following year the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, shortly after the assassination of Dr. King in 1968, the Fair Housing Act was signed into law.

Ok, but now, what were Quakers doing during the Civil Rights Movement?

George Lakey

I think it did teach a lot of Quakers the importance of taking risks and seeing the expression of social movements as a primary way of changing society for the better. And before the Civil Rights Movement, I think that people had lost that sense.

Georgia

That’s George Lakey. George lives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He describes himself as a happily retired 86-year-old. He’s got a huge, infectious laugh, which you will definitely hear today, and he’s been a champion for nonviolent action — both in the states and abroad — for some 60 years. In fact, he literally wrote the book on it.

So, I called George up to ask him about the broader Quaker context during the Civil Rights Movement and his own activist work.

George

A Quaker difficulty, I think, in addressing the movement was that a lot of Quakers by then were being brought up by upper middle class people. Upper middle class professional people tend to be conflict-averse and tend to rear their children to behave and do what’s expected to be done and not make trouble.

Georgia

There seems to have been a general stance that racism and segregation were wrong, but in practice there were Quaker individuals, meetings, and organizations that kept their distance from Civil Rights work or even actively upheld segregation.

Take the Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C., which remained segregated until 1956, even after years of calls to integrate. Jimmy Stone was the chair of the board and a lifelong Quaker and he wrote that he was “frankly puzzled” as to why it would be “unchristian” to prohibit Black children from attending school with white girls and boys.

Of course, many Friends schools did integrate earlier, but even Greensboro, North Carolina’s Guilford College — a place that had been on the tracks of the underground railroad — did not welcome Black students until 1962.

Now all this is not to say that Quakers were absent from the movement by any means. Some Friends practiced a quiet, behind the scenes diplomacy to move white Quakers and white people in positions of power toward racial integration. Here’s George Lakey again.

George

There were Quakers like me who joined the Civil Rights Movement because we believed that nonviolent direct action was the way to go, that it would take that kind of pressure to really open things up. And so we would meet together yearly and fight with each other about which was the more effective method.

Georgia

That group was called Friends Concerned About Race Relations and George says about 3 or 400 Friends would meet yearly to compare notes.

There were many Quakers who were busy during this time. For example, one Friend I spoke with said that Midwestern Quakers joined with other religious groups in massive letter writing campaigns that helped to push the envelope on both the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts but…

George

It never became anything like 80% of Quakers involved because Quakers have a number of other concerns, but it was also heartening to know that folks were working on other avenues because, of course, racism is so systematic that really addressing the whole system does make a lot of sense. It’s just that some of us believed, well, the Quaker heritage leans strongly toward non-violent direct action. In the 1600s, which is when we were born, we were in trouble all the time. So I thought troublemaking was the shining thing for us to do, but not everybody agreed with me.

Georgia

George’s own anti-racism stance began in childhood and by the time he was in his early 20s, he was itching to get more involved in the now full fledged movement.

George

I was reading about it every day, listening to the reports on the radio, very excited, and realizing, hey, wait a minute, all the photographs in the newspaper, of people being arrested and so on are Black people, which gives the impression that civil rights is a Black people’s concern. But hey, it’s a white people’s concern.

Georgia

So he went to get arrested, to a town near Philadelphia where sit-ins were happening at city hall.

George

I was the only person who got into city hall because I was white, so I could walk right past the police into the city hall and my black comrades of course couldn’t do that. So I go in there and the place is empty because of the emergency. And so a police officer came over to me and said, so, can I help you? You know, thinking I’d come to pay my water bill or something.

And I said, yes, I’ve come to sit in. And he said, go ahead, if that’s what you came to do. So I sat down and expected to be arrested right away.

And he smiled at me and he said, okay, so obviously, you’re now a hero, you can go home and tell your friends that you’re a hero. I said, oh no, I’m serious about this. I’m sitting here. And he said, oh okay, in that case. So he gets a couple of the people he’s commanding to come over, pick me up, throw me against the wall, start beating me and arresting me. And so that was my first time getting arrested in the Civil Rights Movement and really feeling like I was a bonafide part of the struggle.

Georgia

Inspired by Martin Luth King, George had transferred to a historically Black college. He was the only white student on campus.

George

My anti-racism was, you might say, a matter of principle, but not of experience. I think it was a big help that I’d had that experience of comradeship with Black people completely surrounding me, I was the only white student on campus, that really helped me to step into becoming bolder and participating.

Georgia

While working on his graduate degree at the University of Pennsylvania, George and his friend wrote A Manual for Direct Action, which has since revised and updated under the title How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning.

George

Marty Oppenheimer said, George, we need a manual because there are people getting hurt. In fact, there were people getting killed in the Civil Rights Movement because they didn’t know some of the things that we knew about how to maximize safety while still giving a big problem and keeping that awareness going. So we thought, let’s have fewer deaths by having a manual that helps people be more thoughtful. And so we went ahead and did it. We kept saying, somebody else should write it. Bayard Rustin should write it. Somebody with way more experience, who is Black, should be writing this manual. And then we realized, Bayard has no time to write a manual.

Georgia

They sat down and wrote it in a few weeks, got a Quaker printer to print it overnight and sent a thousand copies South.

George

Just in time for Mississippi Summer of 1964.

Georgia

A commercial publisher got wind of the book and asked to publish it.

George

So we, you know, we gussied it up a little bit and made it a little more coherent, and so it was put out as a paperback; we were very proud.

Georgia

While George Lakey advocated for nonviolent action in Philadelphia, our next guest was getting involved a few hours away in Washington, D.C.

David

I’m David Hartsough. I live in San Francisco. I grew up in the Philadelphia area. I’ve been involved all my life in work for peace and justice.

Georgia

David is the co-author of Waging Peace: Global Adventures of a Lifelong Activist and, like George Lakey, he has worked all over the world to advocate for peace through nonviolent action.

David actually got a first-hand look at the Civil Rights Movement early on.

David

Had the good fortune of meeting Martin Luther King when I was just 15 years old.

Georgia

David’s father had worked with Ralph Abernathy, a confidant of Martin Luther King, and Ralph invited David and his father to see the Montgomery Bus Boycott in person.

David

And that was a life-changing experience for me where I met King and met thousands of people that were walking to work every day instead of riding the buses, the segregated buses.

Georgia

It was spring of 1956.

David

And we saw churches that had been bombed. One church, I remember inside the pews were just splinters of wood. It was very touching to me that the whole spirit of that movement was not vengeance.

Georgia

After a year at Swarthmore College, he was led during a Quaker worship service to transfer to the historically Black Howard University.

David

And during that worship, I felt God was speaking to me more than any time in my life. And I heard God saying, “David, go to Howard University.” And it was so clear that the next day I walked over to Howard University across town to find out how to register to become a student there.

Georgia

While there, sit-ins began to break out across the country as Black students and white allies challenged whites only businesses. David and his friends found that while DC was already desegregated, nearby Maryland and Delaware restaurants were not.

David

A bunch of us did nonviolence training, and we went out to Maryland. We’d sit at a lunch counter on a Saturday morning and be arrested. We sang freedom songs the whole weekend and built community in the jail. And we would be released and go back to classes on Monday. So that’s the way I spent many of my weekends that spring of 1961.

Georgia

Then David and his friends decided to go to Virginia, which had much steeper fines and where the Ku Klux Klan was already known to be harassing protesters.

David

So after our final exams in June, we went down just across the river into Arlington to what was called the People’s Drug Store. And we sat down at the lunch counter. And it turned out that the owner wasn’t going to serve us. He put up lunch counter closed signs.

But he also decided not to arrest us. He didn’t want the publicity. So we sat there for two days waiting for something to eat. And it was the most challenging two days of my life. People came up and spat at us in the face. They put lit cigarettes down our backs, our shirts. People would punch us in the stomach so hard that we would fall on the floor, and then they would kick us.

And each time something like this would happen, we would try to respond in a nonviolent, loving way. The American Nazi Party did come with their swastikas and using all kinds of violence against us.

Toward the end of the second day, I heard a guy come up from behind me and he said, “If you don’t get out of the store in two seconds, I’m gonna stab this through your heart.”

I looked at him in the eyes and his eyes were filled with hatred. And in his hand was a switchblade. I had two seconds to decide, do I really believe in nonviolence or is there some other way to deal with this guy?

We’d had a lot of practice and done role playing about situations like this. I just looked at him in the face and said, “Friend, do what you believe is right, but I’ll still try to love you.” It was absolutely amazing. His face that was contorted with hatred, his jaw began to drop and his hand with the switchblade began to fall and he left the store. And something in the way I responded to him had touched his humanity.

But it was, I think, the most important lesson of my life that when something terrible is happening, you don’t have to just curse the television set or the president or segregation or war. You can find some other people that believe as deeply as you do, get some nonviolent training, and go and challenge that violence, stand in the way of it. So that’s what most of my life has been about since then.

Georgia

So far, we’ve been pretty far north, but after the break, we’re going to look at how Quakers responded to segregation and the Civil Rights Movement from the other side of the Mason-Dixon line…

Jon

Hi dear listener! It’s Jon here and I wanted to hop on and tell you about something exciting we are starting in 2024. By now you’ve probably gotten used to a short piece in this mid-episode break telling the story of a listener, and asking you to become a monthly supporter of the podcast. I’ve heard from a surprising number of listeners that it’s actually one of their favorite segments on the show, and that’s pretty cool, considering that it’s basically an ad. So, that’s not going away.

But we aren’t the only ones doing good work that needs support in the Quaker world, not by a longshot. In fact, you may know of an organization or a project that could use more visibility and we want to help. After just one season, our audience now averages around 3,500 listeners per month and that number is growing. We have found those listeners to be thoughtful and engaged folks–of course you should know, since you’re one of them.

So here’s what I’m building up to — if you know of an organization or a project that could use more visibility and support, and could maybe benefit from some media creation and storytelling expertise, we want to help. This space right here in the middle of the episode could be dedicated to telling the story of your project, and that could have a major impact. Just reach out to us at QuakerPodcast.com/contact and let us know about your idea.

Ok, back to the show.

Georgia

Welcome back.

Ok. So, we’ve established that Quakers did some amazing things during the Civil Rights Era and also that they sometimes were actually opposed to integration. The same holds true for Quakers in the South and among Quaker meetings.

I asked author and activist Chuck Fager how Southern meetings approached segregation during the movement.

Chuck Fager

Segregated by policy, I don’t know. I doubt it. Segregated in fact, yes.

I do have a case study. Willy Frye moved to North Carolina became a pastor in North Carolina in the 1950s. He read the North Carolina yearly meeting Book of Faith and Practice, and it had a section on racial equality, and for its time it was pretty right on it said people were all equal and racism wasn’t good and Quakers are supposed to treat everyone as brothers and sisters and yada yada.

And that was completely ignored, but it was in the book. And Willie Fry read the book, and he thought, oh, gee whiz. And so he invited a few people of color to come visit Winston Salem Friends Meeting, just to come to meeting, not necessarily to join. But you know one thing leads to another. And the fact that he did that, that meeting ended up splitting.

They left to preserve segregation. They were officially not segregated. De facto they were, and some of them were ready to fight about it.

Georgia

The Atlanta Friends Meeting was a completely different story. Founded in 1943, the identity of the Atlanta Friends has been one of peace and racial equality since it was established. And that attracted Don Bender to the meeting after he moved there in 1966 at the age of 26.

Raised in a Mennonite tradition, he first lived in a house for Mennonite volunteers but soon connected with the Quakers.

Don Bender

As I got more exposed to people in the Civil Rights Movement and discovered that there was a social action arm of the Atlanta Friends meeting called Quaker House, which was more actively confronting segregation. It was much more attractive to me, the Quaker House, and then through that got involved with the meeting itself.

Georgia

As he became involved with the Quakers, he says he came to focus on responding to the God within him and in others.

Georgia

How did that affect your social justice work and the civil rights work you were doing?

Don

It strengthened it. It’s not just a matter of we were taught by Jesus to love our enemies, but that in fact our so-called enemies were also children of God, had that of God within them. And so that put it at a deeper level. It was not mine to take another person’s life, but not only that, that it was mine to respect the dignity and the rights of everybody.

Georgia

The meeting members played an active role in their city.

Don

I don’t think there was anybody who was not on board with racial justice. That was pretty much a given and we were, right from the beginning, have been so identified with integration. People that were involved in the meeting were involved in integrating the YMCA for example and the transition to integration of the public schools and that kind of effort.

Georgia

When he moved to Atlanta, Don had imagined himself protesting on the front lines, but he found that the work that he was more called to do, as a white Mennonite and Quaker, was to support Black organizations in their struggle for equality and to build up the community.

Don

That then segwayed into more focus on anti-war activities. And so Judy and I, my wife and I, lived at Quaker House for a couple of years and our focus was mostly on anti-war activities and on draft counseling.

Georgia

Don and his wife and their community continued to work to bring peace and racial equality to Atlanta.

Actually, Quakers worked throughout the South, including in South Carolina’s African American Gulleh Geeche community on St. Helena Island. Formed after the Civil War, the Quaker Penn School was a place where the area’s mostly impoverished Black children could go to school. But in the 1950s it became the Penn Center with the help of Quakers Courtney and Elizabeth Siceloff. The center was a place where Blacks and whites could gather together.

Staff at the center supported voter registration and school desegregation. And the space was used for nonviolent training. The likes of Dr. King held workshops there and it was the headquarters for the first planning session for the March on Washington.

Others joined Freedom Rides to the Deep South, and, then there was AFSC.

If you are at all familiar with Civil Rights and Quakers and Quaker organizations, then you might be wondering why I haven’t yet mentioned the American Friends Service Committee. Well, let’s talk about them right now.

Very briefly, AFSC is a Quaker nonprofit that started in 1917 to provide alternative service opportunities to conscientious objectors during World War I. During the Civil Rights Movement, AFSC was very active in a lot of areas, so I called up University of Louisville history Professor Tracy K’Meyer to tell me more about their work.

Tracy

I’ve just published a book called to Live Peaceably Together: The American Friends Service Committee’s Campaign for Open Housing, which gets into these issues of Quakers and race, the AFSC and race, the AFSC and housing, specifically.

Georgia

We’ll discuss their housing initiatives in a few minutes, but first, let’s look at their work in the South. One of their most well-known initiatives was in Prince William County, Virginia. After Brown v. the Board of Education, schools in some districts decided to close entirely instead of integrating. That left Black students with nowhere to go, so AFSC worked with Black families in Prince William County to create educational opportunities for their children and ended up staying for six years.

AFSC also had regional offices throughout the South from which they deployed both staff and volunteers, from Little Rock, Arkansas to Greensboro, North Carolina.

Tracy

So a lot of times what would happen is those regional offices would do programming around civil rights issues. So a lot of it was in these sort of sending staff people to a crisis spot to work on reconciliation, to help Black families through a difficult situation. Not necessarily like organizing its own campaigns, and part of that is because a really big kind of fundamental philosophy of the leadership of the domestic work was you should be putting the local people up front. The AFSC’s job is to support local people who are doing something, and they almost had like an allergy against taking credit for things.

Georgia

In the north and west, AFSC focused much of their work on housing integration. Building resources had gone to the war effort, so by the end of World War II, American cities were experiencing a severe housing crunch and African Americans were the most heavily hit, says Tracy.

Tracy

Almost immediately after the war, of course, by the late ’40s, you start getting the, you know, sort of the rise of the post-war suburbs and federal programs to help people to move to them, but those are completely shut to African Americans.

Georgia

AFSC saw violence erupt in multiple cities and understood that the problem of race and housing are tied. They were also getting requests from Quaker meetings to send help.

Tracy

And so they start these housing opportunity programs, initially it’s really to try to convince banks and builders, et cetera, to serve African Americans, and then it kind of goes from there.

Most people at the time recognized that the AFSC was a leader on this issue. They were the organization that had the staff, that had the expertise.

Georgia

But it’s hard to measure the success of this work.

Tracy

Housing is still segregated in most major urban areas.

Georgia

They tried to change the minds of the people holding the purse strings.

Tracy

That’s a failure. So what do we do next? Okay we work with individual black families to help them move into suburban areas, and that works for individual families in that they’re they do succeed in helping black families to find housing. It’s tiny numbers.

Georgia

AFSC staff would go so far as to move into the homes of Black families who were being harrassed, knowing that such efforts would help that family but would not have a wide impact. They were moving the needle in other ways though. AFSC’s Bill Moyers convinces the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to focus on housing in Chicago and he helped negotiate fair housing there.

Tracy

But the little story that I always like to tell, and I tell it late in the book, was in the Philadelphia office. The director of the program, a man named Nate Green, and two women, Barbara Krasner and Julia Robinson, were hired to do testing of real estate firms. So Krasner was white, Robinson was Black. They would choose a real estate firm. Krasner would go in, get served. Julia would go in, not get served. And they documented this. All housing that had to do with federal funding. And they create a report, you know, “The Report to the President” is the name of the report and it documents in explicit detail the way that these discrimination happened.

A group of congressmen notice and really use it in the lobbying for the 1968 fair housing legislation. So I think that you can see like this connection then between the kinds of work they’re doing and what does end up becoming law.

Georgia

Tracy says that for AFSC’s volunteers and staff— there was an underlying spiritual conviction that appears in a lot of their documentation.

Tracy

Well what’s interesting to me is how it just underlies everything, right, in implicit ways and often in explicit ways. Everything from the founding of the Race Relations Committee to sort of their discussion about tactics is always based in basic ideas of, you know, that of God in everyone, the leanings of the Inward Light, their goal is reconciliation, bringing people together and overcoming differences and helping to bring about sort of racial reconciliation.

Georgia

That commitment to peace, equality, and racial reconciliation is one that played out time and again among Quakers during the civil rights era, often in unseen ways.

And that brings us to next week’s episode where we’re looking at the life and activism of Bayard Rustin — a Black, Gay, Quaker who, for a long time, was long a footnote in Civil Rights history,

Micahel Long

Bayard Rustin, who had been kept in the shadows almost his entire life, comes roaring out of the shadows of Abraham Lincoln. He takes his spot at the podium in front of this huge bank of microphones, and he raises his right arm, and he makes a fist. And he leads the people in affirming each of the demands. What do you say? Bayard yells out and the people roar their response. It’s a beautiful moment.

Georgia

Thank you for listening and thank you to all of the people who spent hours speaking with me for this episode. I’d also like to thank Stephen Angell and Althea Sumpter who provided valuable historical context.

For more information on today’s topic from an African-American perspective, check out Fit for Freedom Not For Friendship: Quakers, African Americans, and the Myth of Racial Justice By Donna McDaniel and Vanessa Julye and Black Fire: African American Quakers on Spirituality and Human Rights Edited by Harold D. Weaver Jr., Paul Kriese, and Steven W. Angell.

Find links to those books and books by George Lakey, David Hartsough, and Tracy K’Meyer in our show notes. Please also head over to our episode page to leave a comment on this episode.

This episode was produced and edited by me, Georgia Sparling. The music was written and performed by Jon Watts.

Studio D mixed the episode and your moment of Quaker Zen was read by Grace Gonglewski.

Thee Quaker Podcast is a part of Thee Quaker Project, a Quaker media organization whose focus is on lifting up voices of spiritual courage and giving Quakers a platform in 21st century media.

If you want to support our work, please consider becoming a monthly supporter. Every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way and makes this project more sustainable!

Visit QuakerPodcast.com for more information.

And now for Your Moment of Quaker Zen.

Grace Gonglewski

William Penn, 1682, “No Cross, No Crown”: “True godliness does not turn men out of the world, but enables them to live better in it, and excites their endeavors to mend it; not hide their candle under a bushel, but set it upon a table in a candlestick.”

Georgia

Sign up for daily or weekly Quaker wisdom to accompany you on your spiritual path, just go to DailyQuaker.com. That’s DailyQuaker.com.

Recorded, written, and edited by Georgia Sparling.

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Mixed and mastered by Studio D.

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Image: Gwendolyn Greene and David Hartsough sit at the People’s Drug Store counter. Image courtesy of DC Public Library, Star Collection

Further reading:

- How We Win: A Guide to Nonviolent Direct Action Campaigning by George Lakey

- Waging Peace: Global Adventures of a Lifelong Activist by David Hartsough and Joyce Hollyday

- To Live Peaceably Together: The American Friends Service Committee’s Campaign for Open Housing by Tracy K’Meyer

- Learn more about Chuck Fager and his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement on his website, A Friendly Letter.

- Fit for Freedom Not For Friendship: Quakers, African Americans, and the Myth of Racial Justice By Donna McDaniel and Vanessa Julye

- Black Fire: African American Quakers on Spirituality and Human Rights Edited by Harold D. Weaver Jr., Paul Kriese, and Steven W. Angell