Who Are Modern Quakers?

Quakers today can be found all over the world, and they identify as everything from evangelical Christians to atheists. Yet, they are all dedicated to being Quakers.

For our first episode (yay!), our producer Georgia goes on a quest to explore 21st century Quakerism by talking to Quakers on three continents.

What does it mean to be a Quaker today? What separates different kinds of Friends and what unites them? And what does the future look like for this global denomination?

Let’s just say, those weren’t easy questions to answer.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Want to contribute to upcoming show? Leave us a voicemail at 215-278-9411 and let us know what the word “Quaker” means to you.

Was there something in this episode that stuck with you?

What does modern Quakerism look like where you are?

Share your thoughts below!

Woman at Friends International Center

Hallelujah. Amen. In the book of Psalms, we are told that every person that has prayed, let him praise the Lord hallelujah.

Georgia Sparling

That’s a little bit of the service at the Friends International Center in Nairobi, Kenya. Friends, by the way, refers to the Religious Society of Friends, which is the more official term for Quakers. This service is broadcast every week on Facebook. And from what I can see of the church, it’s carpeted in red with a thick, shiny grey curtain that serves as the backdrop to the stage. There’s a worship band with nine or 10 singers, a couple of guys playing guitars and a keyboardist. This is not like the Quaker services I’ve been to so far, they’re more like this.

Warning, you might need to turn your sound up a little.

That was the sound of shuffling feet, squeaking pews, and centered breathing at Central Philadelphia Monthly Meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The floors here are wood. The pews are wood. And like traditional Quaker meetings, the room is arranged such that there’s no real focal point, nowhere for a minister to preach, because here, everyone seated in the pews is a potential minister. Everyone can stand up at just about any time and address the meeting with a message. Now both of these groups strongly identify as Quaker, but they have wildly different ways of practicing. So what does modern Quakerism look like? today? We’ll see if we can figure that out.

Intro Theme

Thee. Thee. Thee. Thee. Thee. Quaker Podcast. Story, spirit, sound.

Georgia Sparling

Welcome to Episode One of Thee Quaker Podcast. I’m Georgia Sparling, your co host and producer of this show. You’ll learn more about me in a minute.

Jon Watts

And I’m Jon Watts. I’m the founder of Thee Quaker Project and this podcast. Before we jump into the show, I just want to say thank you so much for listening. I’m really excited that you’re here and want to tell you a little bit about what to expect on this podcast. Thee Quaker Podcast is a weekly show, we’re exploring all sides of Quaker spirituality.

Georgia Sparling

Every episode, we’re going to lift up a different aspect of the faith. Whether it’s a story of spiritual courage from the present, or the past, an interview with someone who’s doing really exciting work, or an exploration of a notable practice.

Jon Watts

We’re also going to explore the future of Friends and what it means to be living in the 21st century as Quakers. We’re going to explore big questions that just about everybody has,

Georgia Sparling

Both Quakers and non Quakers.

Jon Watts

And every episode, we’re going to share stories of spiritual courage by delving into the lives of Quakers from the past and the present. And we’re going to have conversations about the future, about modern life and spirituality.

Georgia Sparling

We really want this to be a podcast for spiritual seekers, lifelong Quakers, and everyone in between.

Jon Watts

We have so many stories planned, but first, we just wanted to start out with the big picture. What does Quakerism look like today?

Georgia Sparling

And that is a big question a bit bigger than I realized when I first set out to report on this topic.

Jon Watts

Yeah, tell me more.

Georgia Sparling

Okay, so even though I’m the host of this fine Quaker podcast, I am not in fact, Quaker.

Jon Watts

Okay. I did. I did know that about you.

Georgia Sparling

Anywho. Before taking this job, all I really knew was that Quakers usually worship in silence. They were a small Christian group. They like to write letters to their congressmen, and at least the Quakers I met were a little quirky, delightfully quirky. That’s not a criticism.

Jon Watts

No, no offense taken. We do know that we are a peculiar people. So anyway, what what did you discover?

Georgia Sparling

That there are Muslim Quakers, atheists Quakers, Catholic Quakers, even a Quaker who identifies as a shaman, and as I was doing my research, I realized it was really going to be a challenge to answer the question, what is a modern Quaker? So for now, I’m going to do my best to give a really broad overview of this topic, and the reason I am saying all this is because I don’t want people to be mean and @ me on social media about all the things I missed.

Jon Watts

I do want people to @ you on social media, but I don’t want them to be mean about it.

Georgia Sparling

Right. So okay, are you ready for the story?

Jon Watts

Let’s do it.

Georgia Sparling

Here we go.

Marge Abbott

The standard approach is to keep with this founding story set in Britain and the US.

Georgia Sparling

That’s Marge Abbott. She and her husband Carl wrote “Quakerism: The Basics,” and it was one of their priorities to emphasize just how global Quakerism is today. While Quakerism seems most often to be affiliated with Britain and the United States,

Marge Abbott

There’s the reality that of Quakers worldwide, half of them are in Africa. Another third of them are in Latin American and in what 20% are in the us. We’re definitely not but even majority of Friends worldwide.

Georgia Sparling

There are pockets of Quakers all over the place — Indonesia, Nepal, Guatemala, Croatia, Malta, Bhutan, even Hong Kong — but Kenyan friends make up the lion’s share of Quakers today, and they are growing. While there are an estimated 400,000 or so Quakers worldwide. Dr. John Muhanji believes that there may actually be more than that in Kenya alone. Dr. Muhanji is the African Ministries Director of Friends United Meeting. He lives in Kisumu, Kenya, and overseas missions for the organization, which has planted churches, schools and other initiatives in countries including Burundi, Rwanda, Zambia, and Tanzania.

Dr. John Muhanji

And I can assure you, the world is looking for Quakerism for Quaker values.

Georgia Sparling

Kenyan Quakerism is solidly evangelical.

Dr. John Muhanji

So the church in Kenya is pastoral in nature, evangelical in nature, and is not silent, it’s vocal. That means, we sing, you come to our worship, prepare to sing, prepare to dance, we and you will, we will dance as we sing our hymns. We pray vocally loudly, we don’t just keep quiet. So there is only one silent meeting in the whole of Kenya.

Georgia Sparling

Kenyan Quakers talk about Jesus, they sing about Jesus and they preach about Jesus. Honestly, they seem kind of Baptist-y to me, except for the fact that like most Quakers, they don’t take communion or perform baptisms. But these Kenyan Quakers are a lot different from those in the United States and the UK. I asked Anna McCormally, a lifelong Quaker, to tell me about her experiences. Anna was raised in the Herndon Friends Meeting in Herndon, Virginia, not too far from Washington, DC, where she now lives.

Anna McCormally

My meeting was not, we were not a Jesus meeting. I did not, we very rarely like referred to Jesus other than as a teacher. So Jesus was not, I think, I guess a divine figure for me.

Georgia Sparling

I had already started to pick up that there was a big range of beliefs within Quakerism. But I was still kind of surprised that Jesus would not be a central figure at all Quaker meetings. Anna’s meeting was very traditional in the sense that it was a silent meeting.

Okay, time for a quick sidebar. Quaker meetings generally fall into three different formats. Unprogrammed are silent meetings. These are like the second clip I played at the top of the show. In these meetings, Friends, listen, worship and meditate in silence, and anyone may stand up if they have a leading, which means they have a message to share. As far as I can tell, these unprogrammed meetings are more likely to have a variety of beliefs represented — from atheists to Jesus followers.

Then there are programmed meetings. These tend to be more Jesus centric, and they often call themselves churches. These are kind of like the services that I grew up in there’s singing, a pastor who gives a message, etc. There’s little if any intentional silence in these meetings.

Sandwiched somewhere in the middle are semi programmed meetings, where you guessed it, there’s singing, a short message and a period of silence. One day we’ll explore all of that, but for now, suffice it to say that when Anna went to a Quaker college, she discovered variances from the Quakerism that she wasn’t used to.

Anna McCormally

I had the opportunity when I went to college to meet Quakers from different parts of the country. And I remember being surprised at how different it was, but the way that like being for worship looked and also in the values I think like things that I took for granted as part of Quakerism, I was surprised to find out what like, foundational everywhere. Like I, I’m not surprised by this anymore but when I was younger, maybe like 10 or 15 years ago, and I first found out that there were Quakers who were like anti same sex marriage, for example, I was like, oh, I that never even occurred to me as a thing that could be possible because the meeting where I grew up so, like that wasn’t even like a topic of conversation.

Georgia Sparling

As I said, there’s a huge range of beliefs in the Quaker denomination. I mean, some Friends would not even call it a denomination. Quakers don’t traditionally have a creed, but they do have a whole Quaker vocabulary. But in it, I haven’t often heard words like salvation or gospel or Trinity, which formed the scenery of my own faith background. Admittedly, I know, I still have a lot to learn. What I have noticed is that Friends do often quote George Fox when they talk about their beliefs and their relationship to other people. Fox is regarded as the founder of Quakerism, and he had this idea of “that of God” in everyone.

Anna McCormally

How I experienced Quakerism growing up, was I think, if I had to sum it up, I would say there’s “that of God” in everyone.

Georgia Sparling

Present day Quakers talk of an inner light that may or may not be connected to a belief in a higher power, depending on the person. Some refer to the Divine as Spirit, some say God, some say Jesus. There are robust discussions about the many flavors of Quakerism on myriad Facebook pages, Quaker subreddits, and blogs.

At least in some pockets of Quakerism, there are Friends who seem either disconnected from or not engaged in the Christian origins of Quakerism. But I found myself wondering if you could actually divorce the two. Ashley Wilcox is the interim pastor of New Garden Friends Meeting in Greensboro, North Carolina, and the author of “The Women’s Lectionary.” She identifies as a Christian preaches using biblical text. And she has something to say on this topic.

Ashley Wilcox

And I think not everyone knows that Quakers came out of Christianity. If they came to Quakerism, with a very liberal unprogrammed, or more like humanistic meeting, they might not know. We also just get so many religious refugees, we get a lot of people who are hurt by their church background. And they want to get as far away as they can from anything that reminds them of that.

Georgia Sparling

Ashley, who is something of a religious refugee herself, can see where they’re coming from. But she also believes that there’s something worthwhile about exploring Quakerisms origins.

Ashley Wilcox

Going deeper within this tradition, understanding what is actually within it. It is active listening for the voice of the Spirit. And I am open to all of the different ways that people name that. But when people are like, No, you can’t talk about God in a Quaker Meeting. That’s when I’m like, that’s a little too far for me. And it seems to me like it’s coming out of their own unexamined woundedness rather than a real place of listening to the Spirit together.

Georgia Sparling

So at this point, I was kind of in a head spin. How could there be Jesus Quakers and Muslim Quakers and atheist Quakers and evangelical Quakers? And honestly, why do they all hold on to this one word Quaker as their identifying marker. After the break? We’ll try and answer that question by exploring areas where Quakers find common ground.

Erin Bates

Hey, Jon,

Jon Watts

Hey, Erin, how are you?

Erin Bates

I’m good. How are you today? Can you hear me? Yes.

Jon Watts

All right. Thanks for taking a second to talk with me.

Erin Bates

Yeah, for sure.

Jon Watts

So you and I have been in touch a lot recently because we’re working together on the Intermountain Yearly Meeting gathering in Colorado this summer. And at some point in that process, you mentioned that you were relatively new to Quakerism and that my work had played some role in that. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about that story.

Erin Bates

Yeah, absolutely. So I first went to a Quaker meeting in November of 2021. And before that, I was part of a very, very conservative, fundamental evangelical Christian church, and my partner was not. And we were trying to figure out how to mesh our beliefs together. And he asked me to go to a Quaker meeting with him. So I opened my heart a little bit to the thoughts of Quakerism. But I didn’t know if I felt comfortable going to an actual meeting with people.

So I started looking on the internet about, you know, what is Quakerism. And very quickly, I found Quaker Speak. So, I remember very specifically, the first one that I watched was “Are Quakers Christian?” And there was an interview that said, in Quakerism, there are no lay people because we’re, we all have God in us. And I thought that was a really beautiful sentiment. This really started kind of opening my eyes to that the Quakers each had their own faith, and that that was okay. And that the group as a whole was not purposed to change my faith or tell me what to believe, but that rather, it was a guide to help learn how to live in this. I think the video might have even called it a “dynamic spiritual presence,” where we’re focused on community, and we’re focused on helping people in the world right now. That’s what convinced me to go to a meeting.

And so I went to my first meeting at Mountain View Friends Meeting with my partner. We heard some of the, I think it was the Peace and Social Justice Committee, they stood up and they said there was a recent shooting at a Jewish synagogue. And that Mountain View was looking for people to volunteer to go stand outside of a Jewish synagogue on one of their upcoming Holy Days, because they needed a peaceful nonviolent presence, so that the Jewish people could go and worship and peace, and that just sealed the deal.

Jon Watts

Thank you so much, Erin. I appreciate you doing this spontaneously.

Erin Bates

My pleasure, Jon. Have a good rest of your day,

Jon Watts

Okay, you too.

Jon Watts

If you’d like to support our work, we want to keep having rich conversations, like the ones that Erin discovered online that led her to Mountain View Meeting. This weekly Quaker podcast that you’re listening to right now is listener supported. So you can make a big difference by going to Theequaker.org and pledging a monthly donation to our Patreon. Thanks so much for your consideration. And now back to Georgia.

Georgia Sparling

Welcome back, okay, so Quakers may be Christians, they may not be Christians, they may worship in silence. They may worship loudly with singing and dancing. And they could be just about anywhere in the world. But I wanted to know what if anything unites all or at least most Quakers. Here’s Dr. Mohanji again.

Dr. John Muhanji

We carry out the Ministry of Peace, very, very passionately. We have involved ourselves in peace development in this country. In 2007, and 2008, we had a post election violence that rocked the entire country. I can tell you, we got engaged, head on, directly with the people who are causing violence, and we participated in bringing peace.

Georgia Sparling

This is a topic that came up over and again, during my reporting — the peace testimony. Here’s Carl Abbott, who co wrote “Quakerism: The Basics” with his wife, Marge, who you heard from earlier.

Carl Abbott

So the peace testimony can be conscientious objection to war, or it can mean an emphasis on peacemaking and reconciliation. So it’s not only personal, you know, a personal testimony but a kind of community testimony to build peace.

Georgia Sparling

The peace testimony is one of the things that has consistently attracted people to Quakerism.

Zachary Moon

A lot of folks who were coming out of the resistance movement around the Vietnam War, in particular, Berkeley was one of the national capitals of that movement. And they found Quakers were a community of like minded like committed, caring, warm, sincere folk, and sometimes it was religious, but really the religious thing was our commitment to peace, that value that belief was really supreme for us. It was central for us. And so a gift of that was activism and faith were never separate things.

Georgia Sparling

That’s Zachary Moon. Zachary is a professor of theology and psychology at Chicago Theological Seminary. But he grew up in the Berkeley Friends Meeting in California. That area was a particular hotbed of activism, peace marches, the whole nine yards. He says the peace testimony was the uniting theme for his community.

Zachary Moon

Our sense of religiousness, our sense of theology, was usually pretty thin. You could find it in little pockets within the meeting, within the yearly meeting, certain individuals who would kind of thicken that in their own lives, but collectively, really, the only thick thing was, we’re here for peace. And we’ve all agreed on that. And that’s, and that’s our central thing. That’s the thing that holds us together. Our sense of belonging is not a theological thing as much as it is this really clear sense of ideological commitment to peace and justice.

Georgia Sparling

Quaker activism goes back to the beginning of Quakerism. Today, modern friends are particularly passionate about racial discrimination, political reform and the environment, especially climate change. For many, social justice is baked into what it means to be a Quaker. Ingrid Leakey, a founder of the Earth Quaker Action Team, grew up attending protests with her Quaker parents.

Ingrid Lakey

I certainly got the idea that we are all to be activists, right? Everywhere you go, if you see injustice, you take it on. So I went to the local public school. And at that time, teachers were allowed to hit students. And I thought that was just wrong. So I was in like, first or second grade, and I’m a Quaker, I believe in non violence, there’s no way it should be acceptable for a teacher to hit their students. And so I refused to go to school. And so my parents were like, that’s totally legitimate.

And so my dad took me to the principal’s office, where I got to make my case for why I was not going to participate in a system that was harming children in this way. I don’t think it changed the policy of the school. But it was an example of my parents, the community seeing a truth that I saw, and backing me up on it, it was a really important part of my growing up and being taken seriously. When I see something that’s wrong, there’s something you can do about it.

Georgia Sparling

Quakers, like all people don’t always agree. But so far, I’ve found that they do have this passionate desire to do something, to act on their beliefs. There’s the sense that it isn’t enough to merely attend a weekly meeting. But there’s another common theme amongst Quakers that of listening for the Spirit or light or God, and speaking truth to the congregation through a testimony or ministry in sound. I know this has been a particularly meaningful part of Jon’s own faith journey. says we’re in the process of working on this, Jon, it was actually you who brought this particular point up. And so that’s why I wanted to bring you in. So could you talk a little bit about how deep spiritual listening and speaking has been a part of your journey as a Quaker?

Jon Watts

Yeah, absolutely. You know, for me, personally, I spent many years as a songwriter as an artist. And when I would write songs, I would often try and write something really great. And then it was it ended up being superficial or feeling like you could hear the songwriters thought process going into it, and it would feel kind of forced, like I was shoehorning ideas into poetry. And then I started trying this thing which I had grown up with in Quakerism, which is waiting, waiting for the song to come to me or waiting for that still small voice to give me the lyrics or the chords or whatever.

Jon Watts

And then I started finding that the songs were much more spiritually inspired and I had more success as a songwriter because the songs felt you could feel that in the song and that there was some kind of magic happening there and 100% that came from my experience with Quakerism that, even without it without a common understanding of what it was that I was listening for, when I grew up in Quaker meeting. Like we, I don’t know that we named it as the Spirit or and we certainly didn’t say the Spirit of Christ. I was more in one of those meetings like Anna was describing, where there wasn’t a very solid theology about what we were listening to in that hour. We still had this experience collectively of sitting and listening and waiting.

And someone wouldn’t stand up in meeting for worship and speak unless they were sure, unless they had been given a message. Even though we don’t present a monolith of theology to the world. If you’re a Quaker, you probably have at some point, had this experience of standing up in front of a roomful of people and feeling compelled to say something that maybe you weren’t planning on saying, and the words come to you in that moment. Because you were listening deeply and you were waiting, and you were given this message, that humbleness that waiting that trying to get out of the way.

It’s only when you are on a Sunday morning meeting for worship, it’s only when you let go of the idea that you’re going to give a message or the that your message is going to sound a certain way that you actually then open yourself up to the possibility of being a conduit for this external energy. And, and that’s a powerful practice that I’ve related to Friends across the theological spectrum about, and it has these incredible implications in our everyday lives, how we make decisions, how we speak, where the words come from. These are all informed by our understanding that we have access to the Spirit in any given moment. But only if we wait on that Spirit and get our own will and egos out of the way.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, wow. Thanks, Jon.

Georgia Sparling

So Quakerism has this rich tradition of activism and deep listening, that there are also some challenges for modern day Quakers, particularly in the quote unquote, Western world.

Rhiannon Grant

So I think it’s quite a community in flux.

Georgia Sparling

Let me introduce you to Rhiannon Grant. She is a lifelong British Quaker, aside from a few minutes during her freshman year.

Rhiannon Grant

I decided I was going to not be a Quaker, I was going to go and try something else. So I went, I went down to breakfast my first Sunday morning at university, and I thought, What am I going to do this Sunday morning, I’m not going to go to meeting for worship. I’ve got up in time for me thing for worship. But that’s just habits. I’m not going to go to meeting for worship.

Georgia Sparling

A group of evangelical Christians and fellow students invited Rhiannon to go with them to church.

Rhiannon Grant

So I thought, Okay, I’ll try out this other church definitely won’t be meeting for worship. And so I went along to their church, and I’m sitting in this school hall, and we’ve sung some hymns, and people have put their hands in the air. And we’ve had a Bible reading, and now we’re listening to the sermon. And I disagreed with that sermon so passionately, I very nearly stood up and shouted back, and I’m sitting there going, I can’t stand up, I can’t stand up. And then I thought, yeah, but that’s what Quakers used to do. And the next week, the next week, I went to meeting for worship, because I was obviously where I was meant to be.

Georgia Sparling

Rihanna is now a writer and she works with the Woodbrooke Centre, a Quaker learning and research organization in Birmingham, England. She’s the kind of person who sometimes wears a badge that reads “I’m a Quaker, ask me why.” Rhiannon says that her community has undergone a lot of changes in recent years, partly because of the pandemic, but also partly because of changes within British Quakerism – some to do with the Quaker involvement in colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade, but also in the identity of who Quakers are today.

Rhiannon Grant

And that means that different people are going in different directions and things like, including non theism in the community, very much under discussion at the moment, active non theists who are really important and serving in the community, and people who are finding that quite uncomfortable and wondering about what the core theological commitments of the community really are. So an ongoing process to balance all of those things and to address the other major issues of our time like the climate crisis.

Georgia Sparling

Many Quakers are taking a look around their meetings and seeing more and more empty seats, an older generation of Friends is passing away and in a lot of meetings, the younger faces are few and far between. That’s got some Quakers wringing their hands and wondering what’s next. Ashley Wilcox isn’t interested in navel gazing.

Ashley Wilcox

I’m not afraid of Quakers dying out because 49% of Quakers are in Africa at this point. And they are growing. Like they grew over 15% in a decade, like they are going strong. Like Quakers might die out in the US, but our denomination as a whole is doing fine.

Georgia Sparling

That might scare some Quakers, but not Guilford Professor Wess Daniels. He wants American Quakers to ask themselves tough questions, and to consider what it is that binds the community together.

Wess Daniels

And it’s not burying your head in the sand. But saying like, if our meeting was to disappear tomorrow, would anyone know we were gone? Would the neighbors across the street know we were no longer here? Do we matter to anybody except for ourselves? And if the answer is no, we only matter to ourselves. What are we doing? What are we doing? That is, that’s not good enough for me. Maybe it’s okay for other folks. That that is not good enough for me, I got plenty of other stuff I need to be doing. I think we have to matter to where we’re placed. And to the relationships that are here in front of us. And I think that building, rebuilding, nurturing that full ecosystem is, is the thing that has in the past, and will in the future, help us to resist the god of empire way more than like just taking one little piece of that out and saying that’s what I got.

Rhiannon Grant

The numerical picture is one thing, but the picture of whether the Spirit is moving, I would say is different. And what I see when I visit meetings is small but committed groups of people who are keeping things going, who are committed to doing it and doing it well, who want to be Quaker who want to participate in that community, and are prepared to put in the work to make that happen.

Georgia Sparling

There are communities where Quaker meetings and Quaker churches are growing, and not just in Kenya. And every Quaker I’ve spoken to you so far is looking to the future. And they’re pretty passionate about what it could look like. At Thee Quaker podcast, we’re invested in deepening Quakerism and lifting up stories that help us understand what this faith is all about. We know that modern Quakers have a lot to offer, and they are actively doing amazing spiritually courageous things all the time.

Jon Watts

Yeah. And by shining a spotlight on those stories of spiritual courage. We know that we get inspired and excited about the future, and we hope you do too. So let’s do this.

Georgia Sparling

Today’s episode was recorded and produced by me Georgia Sparling. Jon Watts wrote and performed the music and also co produced the show. Head over to Quakerpodcast.com to share your thoughts and comments on today’s episode. You’ll also find a link to the transcript and other topics that we discussed today. Thee Quaker Podcast is a part of Thee Quaker Project, a brand new Quaker media organization whose focus is on lifting up voices of spiritual courage and giving Quakers a platform and 21st century media. If you would like to support our work, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter. We are a brand new project and every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way. Visit Quakerpodcast.com for more information, or click on the link in our show notes.

We make this show for you. So thank you so much for listening. And now that you’ve heard from us, it’s time that we heard from you. We asked some of our listeners what the word “thee” means to them. Here’s one of the responses we received.

Arthur Larrabee

This is Arthur Larrabee, Central Philadelphia Meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the Quaker meeting of my childhood, there were several families who use the word thee, and I admired them very much. And there was a quality about the family and the family life that I aspired to. And that’s when I began to use the word thee as the second person singular. For me, the word thee addressing another person in the singular is soft and intimate and evocative of a Quaker tradition. And I use the word thee with my spouse, and with other Quakers, where I want to send a signal, or I want to send a signal of softness and intimacy in conversation.

Georgia Sparling

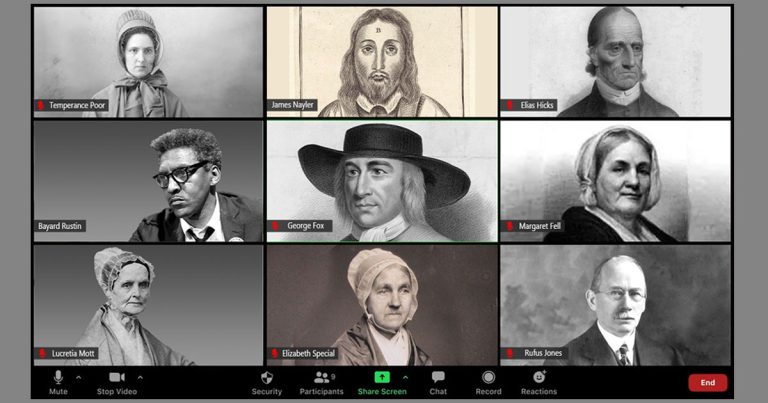

Arthur, thank you so much for sharing that with us. Okay, now it’s your turn. We’d love it if you would give us a call and tell us what the word Quaker means to you. We just might play it on an upcoming episode. You can leave us a voicemail at 215-278-9411. We’ve also included that number in the show notes. Tune in next week as we go all the way back to the beginning of Quakerism with a look at the guy who started it all, George Fox.

Recorded and edited by Georgia Sparling

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Referenced in this episode:

- Friends International Centre Church Ngong Road

- Quakerism: The Basics by Margaret and Carl Abbott

- Learn more about Dr. John Muhanji

- Read C. Wess Daniels’s Blog: Gather in Light

- Find more information on Quaker minister Ashley Wilcox

- Ingrid Lakey is featured on this episode’s art work. Learn more about the nonprofit she co-founded: Earth Quaker Action Team

- Zachary Moon is an author and professor

- Rhiannon Grant is also an author, too! Check out her blog.

Congratulations on this new venture — and “well done, thou good and faithful one” Georgia for doing such a great job of sorting through not only mountains of interviews but the varieties of Quaker experience to offer insight into what modern Quakers are like. Looking forward to future episodes!

Thank you Georgia and Jon, This first episode is excellent! I so look forward to the continuing conversations that will feed those of us who are already Quakers and encourage others to check us out. Combining, deep, spiritual, living with witness in the world is so central to being a Quaker.

Outstanding! In February of 2022 I found Quaker speaks. So I contacted San Francisco Friends and after all this time on Zoom, I will be going in person this Sunday. Yea!

That was wonderful, very rich and very useful. Thank you.

A message from Australian Yearly Meeting:

This year the Backhouse Lecture will be presented by Jon Watts, Quaker film producer from the United States. The annual Backhouse lecture is open to the public, so we encourage you publicise the event and invite interested family and friends.

Join zoom early on Tuesday 4 July ready to be in gathered stillness by 7pm AEST [9:00 am Tuesday, Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)]. The lecture will be delivered live from The Friends’ School in Hobart, Tasmania.

The Zoom link for this session is:

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/84611668562?pwd=R3JqeGcvcHRvbHUxQVgxOHVYOHE0QT09

Passcode: 249421

All are welcome.

2 things i learned from this podcast that we have in common:

Quakers are about peace over the other alternatives

Quakers are about searching for meaning and sharing that meaning with others and listening for meaning from others

and a new thought: in our angst about what we are doing to the Earth, we might find new meaning in searching the ways we Q’s can make peace with the rest of Creation that we have for so long felt we were free to dominate