Why Are Quakers Pacifists?

In a world often governed by force, Quakers have stood apart for centuries with a radical commitment to peace. But this isn’t just a political stance; it is a spiritual practice that challenges us to see the Divine in everyone—even our enemies. This week, we dive into the history of the Peace Testimony and explore how its living wisdom can guide us through modern conflict.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Leave a comment below to share your stories and thoughts!

The Quaker United Nations Office is hiring two Programme Assistants to work alongside its representatives. This 12-month, in person, entry-level position – ideal for recent graduates – provides the opportunity to gain hands-on experience with international peacebuilding through Quaker values at the UN in New York. Applications are due February 16th.

Please consider applying or passing this along to someone who might!

- Max Carter chose to go to a war zone in the West Bank rather than take a safe desk job because he wanted to “remove the occasion for war”. How can we distinguish between simply avoiding conflict (being passive) and actively making peace?

- Bridget describes a “divine thread” or web that weaves the human family together, which violence snaps. When have you felt that thread most clearly in your own life? When has it felt most fragile?

- The episode asks, “When the world demands violence, what does it take to say no?”. For Max, it meant risking the draft; for early Friends, it meant prison. What are the social or professional costs of saying “no” to systems of violence today?

Zack Jackson

The morning of August 6, 1945 started with a strange kind of relief. For weeks, the skies over Japan had been filled with the roar of engines from saturation bombings, but on this particular morning, there was just silence. A five year old girl named Kyoku stepped outside with her brother. Her parents told them to go play. The sky was clear. There were no fleets of bombers. It felt for a moment like a lucky day, and then she heard it. Not a fleet, just one engine. Kyoku looked up. She thought, “Only one airplane. We really are lucky today”.

But then the world turned white, a wall of flame.

Her home was gone. Her parents were gone. Her little brother, standing just feet away from her, was gone. All of Hiroshima was gone.

19 years later, a teenage farm boy in Indiana named Max Carter sat in a church pew and listened to Kyoku tell that story. Max was a patriotic kid. He was planning to join the military, but as he listened to her describe that lucky day, something inside of him broke,

Max Carter

and I knew then and there, I could not participate in any system that made that kind of horror possible.

Zack Jackson

When the world insists that violence is the only way to peace, what does it take to say no, and once you’ve said no, what comes next?

I’m Zack Jackson, and welcome back to season three of Thee Quaker Podcast. In this season, we’ve been digging into the Internet’s most asked questions about Quakers, and today, we are tackling the one that spikes every time the news cycle turns violent, “Why are Quakers pacifists?” If you type that into Google, you’ll probably get a simple answer, but if you ask a Quaker, it gets messier,

Tim Gee

because I think many people aren’t aware that the vast majority of Quakers who have ever lived have not been pacifists, and that is because the word pacifism was only invented just over a century ago, whereas Quakers have been around for nearly four centuries.

Zack Jackson

That’s Tim Gee, General Secretary of the Friends World Committee for Consultation. Pacifism, he explained, is a political strategy. It’s often defined by what you don’t do. You don’t fight, you don’t engage. But early friends weren’t interested in political strategies. They were interested in a spiritual reality.

Tim Gee

So we have our peace testimony. It’s rooted in our experience of the Divine. It’s rooted in our reading of Scripture, but the peace testimony is a cumulative expression of how God has spoken to people, how people have acted on it, and how they’ve reflected on it, usually with the aid of Scripture.

Zack Jackson

The peace testimony isn’t a rule book or a list of best practices for avoiding conflict. It’s a living wisdom tradition. And while modern critics often frame non violence as a naive rejection of the real world, Tim argues that the biblical narrative from Genesis to Revelation tells a different story.

Tim Gee

The Bible starts with a state of shalom. It ends with the state of shalom. We have, of course, the Jesus’s ministry and the the Sermon on the Mount, which begins with the Beatitudes that build up to blessed are the peacemakers, and then works into saying that killing is wrong, but goes way beyond that, asks us to work in reconciliation and and work against various forms of injustice. The first word of the risen Christ is peace. But when you see in the New Testament letters, it says greetings at the top. You know, if it was read in Hebrew, the chances are that they were saying Shalom. So you know, God’s Shalom goes right through the Bible.

Zack Jackson

We tend to assume that the Christian world is hopelessly divided on this, that there are two equally valid theological arguments wrestling for dominance, the “just war” camp and the “peace” camp. But when you really get people in a room, that debate often vanishes.

Tim Gee

The vast majority of times when I would have this conversation with other Christians in an ecumenical setting, I think we would agree on the biblical basis of peacemaking. I think we would agree that war is against the will of God. I think very few people nowadays use biblical arguments for war, where it would very practically go into the more rational arguments, the kind of “but what would you do if you were in such and such a situation?”

Zack Jackson

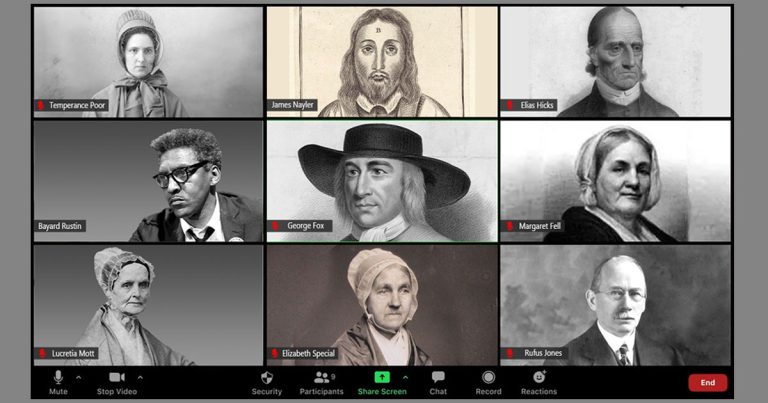

The rational argument, as Tim calls it, is the pivot that we make when the theology gets inconvenient. We talk about necessary evils, about geopolitics and defense, we look at the fruit of war rather than the root that caused it. But early friends like George Fox and Margaret fell weren’t looking at the fruit. They were looking at the soul.

Tim Gee

I think the peace testimony is about identifying what the seeds of war are, what the causes of war are. Depending on your reading or your translation of the Epistle of James says that wars begin with greed inside us, lusts in the soul. According to the King James Version, that was the version that Fox and fell and others quoted,

Zack Jackson

Early Quakers didn’t adopt peace just because the Bible told them so. They adopted it, because they had seen viscerally what war does to the human spirit. Many of the first Quakers were veterans of the English Civil War. They had killed men in muddy fields for causes that they were told were just.

Max Carter

Many of the early Quakers came right out of the New Model Army. They had been soldiers and recognized the horrors of war and came to a position through their experience, as well as the teachings of early Quaker itinerant ministers, that to be a true Christian meant to give up the sword.

Zack Jackson

That’s Max Carter. Again, he’s a retired professor from Guilford College. He told me the story of George Fox sitting in a jail cell in 1650

Max Carter

and was offered early release if he would join the militia. He was recognized as having leadership abilities, and his response was, I can’t, because I live in the virtue of that life and power which takes away the occasion for war.

Zack Jackson

“I live in the virtue of that life and power which takes away the occasion for war”.

But living in that virtue isn’t like a switch you flip. We’re so deeply embedded in a violent culture, that sometimes, we don’t even notice it. Max tells a famous story about William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania.

Max Carter

Penn grew up wearing one of those military uniforms that sons of military folk did, including a sword in the scabbard. And apocryphally, Penn went to Fox and said, “Now that I’ve become a friend, a Quaker, how long can I wear my sword?” And supposedly Fox said, “Wear it as long as thou canst”, implying that eventually the light of Christ would lead him to give it up. And indeed, Penn gave up his sword.

Zack Jackson

Peace is an internal transformation, not just an external behavior, but while individual transformation takes time, political realities sometimes force clarity. By 1660 the English Civil War was over. King Charles the second had returned to the throne, and he was looking for revenge against the radicals who had executed his father. Quakers needed to make it very clear very quickly that they were not a threat to him.

Max Carter

It was an epistle sent to King Charles the second when he ascended the throne, and it was more a kind of a political statement that not us, don’t go after us.

Zack Jackson

Margaret fell wrote a declaration that would become the cornerstone of Quaker pacifism for centuries. She wrote, “We are the harmless and innocent people of God, and we cannot fight with carnal weapons”.

Max Carter

There’s a difference. Difference between “I live in the virtue of that life and power which takes away the occasion for war” and a statement that “don’t go after us, because we aren’t those folk”.

Zack Jackson

It was in many ways, a survival tactic, and while it set a standard, it didn’t settle the debate for the next 300 years, Quakers wrestled with that standard during the American Revolution, free Quakers broke away to fight for independence during the Civil War, many abolitionist friends felt that ending slavery was worth picking up a rifle. The peace testimony has never been a monolith. It has always been a struggle. By 1964 in the Quaker belt of Indiana, Max Carter was living in a community where the peace testimony had become flexible.

Max Carter

So I had an uncle, oddly enough, who had actually been a conscious objector during World War Two, who was a staunch advocate of the war in Vietnam. Because he said, and I remember his words shocked me, “We’ve got to kill the commies for Christ”.

Zack Jackson

Max was 16. The Vietnam War was raging, and he had a plan to do his duty, to serve his country without getting his hands too dirty.

Max Carter

And so I thought, I’ll join the Coast Guard, not knowing then that would lead to hijacking Venezuelan tankers on the high seas later. But figured it if I joined the Coast Guard, I would satisfy the military obligation if I were drafted, but I probably wouldn’t have to shoot anyone, patrol the Mississippi against something rather

Zack Jackson

It was a somewhat uneasy but manageable compromise, that is, until he heard Kyoku’s experience of Hiroshima,

Max Carter

All that thought of kind of compromising and joining the Coast Guard when I turned 18, or when drafted evaporated, and I knew then and there, I could not participate in any system that made that kind of horror possible. And that’s when I became a conscientious objector.

Zack Jackson

In that moment, Max realized he couldn’t participate in the system, but the system had other plans. He was 18, he was healthy, and the United States government was calling him to war. That story after the break.

Jon Watts

Since the earliest days of the United Nations, Quakers have held a presence at the UN headquarters in New York and Geneva, supporting the international community in the collective effort of sustaining peace. But we know today that the UN and other institutions are facing unprecedented challenges; shrinking civic space, increased military spending, and even questioning the basic value of international diplomacy.

The Quaker United Nations Office carries forward with engaging UN diplomats and staff around promoting justice, peace, and sustainability at the UN and is hiring two Program Assistants to work alongside its representatives. This 12-month, paid entry-level position – ideal for recent graduates – provides the opportunity to gain hands-on experience with international peacebuilding through Quaker values at the UN in New York.

Applications are due February 16th. You can apply or find more information at QUNO.org. That’s Q-U-N-O dot org.

Zack Jackson

Welcome back. Max Carter had applied for conscientious objector status, and usually this is where the story ends. The CO stays home, works a desk job and keeps their hands clean. But Max wasn’t looking for an exemption from danger. He was looking for an alternative to violence. So he asked the draft board to send him to war in the Middle East.

Max Carter

Yeah, the Quaker peace testimony is not about just avoidance of war. It’s about how do you live your life in such a way that you help remove the occasion for war? So I wanted to go to a war zone.

Zack Jackson

He ended up at the Friends School in Ramallah in the West Bank.

Max Carter

It was in a war zone, and it was Quaker. And I applied to teach there in 1970 and was accepted. I got dropped down in the middle of the war of attrition, students, Palestinians, whose families had been there for millennia, talking about the impact of the occupation, writing essays about joining thee and wanting to drive out the occupiers. I had to start reading, what is this all about? And after two years of that, you became even more convinced that war is not the answer, that both sides have used violence to get their way, and in some cases, the more powerful of the parties succeeded in imposing a piece a negative peace by crushing the other. But that that does not work, and it just continues a cycle of violence. And so I came out of that experience even more committed to the peace test to. Money and to supporting those non violent responses to oppression and occupation and colonialism.

Zack Jackson

Everyone says they want peace, but it often feels impossible. We’re told constantly that violence is simply the nature of the universe. Recently, Stephen Miller, White House advisor, said on television that we live in a world governed by, “iron laws of strength and force”. He said essentially, that if a nation has the power to take what it wants, it should, and anything else is dangerously naive.

That’s a terrifying worldview. But is he wrong? That does seem to be the way that the world works, right? I put that question to Bridget Moix. She’s the General Secretary of the Friends Committee on national legislation the Quaker lobby in Washington, DC,

Bridget Moix

We are taught history based on wars, but most of the people, most of the time in most of the world, are taking care of each other, are cooperating, are figuring out problems, are working as a community. We rely on each other with a blind faith all the time. Every time I get onto an airplane or a bus, I think about this every time I think about all the people that it requires to get food, you know, that ends up on my table. I mean, we actually are living it peacefully all the time in many, many ways, alongside the wars and the violence and the injustice, those two things exist at the same time. And so we have to keep reminding ourselves and recapturing the real part of our reality, that is the piece that does exist, even amid the war and the violence.

Zack Jackson

We get distracted by the noise of violence. But if you look away from the headlines, you realize that peace isn’t some impossibly naive dream. It is the social contract we are already living by. It is the flight that lands on time. It is the grocery store shelves being stocked. It is the mundane, boring reliability of people simply doing what they said they would do. We don’t notice it because it works. It is just the quiet, functional hum of human cooperation. War is just the moment that hum stops.

Bridget Moix

I really believe that we are meant to be connected to one another, that the divine spark in each of us is a divine thread. It is a divine web that weaves us together as a human family and war and violence break that thread.

Zack Jackson

The web is already there. Our job is to just stop snapping the threads. But when violence is at its loudest, when the threads are snapping everywhere, that is when it’s hardest to believe. It’s easy to trust in peace, when things are calm. But what about when the entire world is on fire? Bridget likes to remind people that FCNL, this Quaker lobby, wasn’t founded during peace time. It was founded in 1943 in the midst of World War 2.

Bridget Moix

One of the words that I love that is in that original document where Quakers gathered and established FCNL, is that they saw that it would be a new adventure, and they were very serious about the work. They named issues that were weighing on Friends, from conscientious objection to humanitarian relief to civil rights, the big issues of the day in this country, that they thought this small group of friends might have a way of working on in in Washington, and they also had that spirit that I find for doing the work of peace building as friends is so important, which is that that sense of the. Walking lightly over the earth, you know, answering that of God in everyone, and bringing some sense of adventure and joy to this very difficult work in the midst of a very difficult time.

Zack Jackson

If they could bring joy and adventure to peace work in 1943, we can certainly do it today, but the doubt still creeps in. Bridget was recently speaking with a young activist who felt overwhelmed by the sheer size of the American war machine.

Bridget Moix

She said to me at some point, well, who’s going to stop the US? And I said, the only people who can stop the us from continuing down this path at this time, is us. It’s the people of the US who have a vote and who have a voice and who can do this work of advocating with our government for a better world.

Zack Jackson: It is a heavy charge. And if you try to carry it alone, you will be crushed by its weight.

Bridget Moix: It can feel like you’re not making much progress, certainly the times that we are in can feel just overwhelming. And I just find again and again that the community that Quakers have built around doing peace and justice work as part of our faith as fundamental to who we are as a faith community, is such a source of strength and resilience. For me, you know, standing on the shoulders of those who came before and trying to become the shoulders for those who will come after, that is a real gift to walk alongside so many people over time in this work,

Zack Jackson: It falls to us, collectively, to shape the world the next generation will inherit. But looking at the headlines today, the forecast is terrifyingly unclear. Tim Gee told me that the Friends World Committee for Consultation is trying to intervene in that forecast. They are making plans for the year 2030—the 2,000-year anniversary of the Sermon on the Mount. The goal is to bring Christians from all traditions together to make a unified, global case for peace. It should be a celebration. But when Tim looks at the predictions for 2030, he sees two very different futures competing for the timeline.

Tim Gee: One news story says that we’ll be in World War Three by then, and the other news story says that there’ll be some kind of tentative, but fragile peace in a number of the hot wars of the world. But you know, whichever of those is our world? In 2030 we’re going to need people who know about peace, who are motivated for peace, who want to work for peace, who want to advocate that resources are put into peacemaking, but we need people who, in the essence of their being, or even from beyond their essence of their being, have something coming into them that they can reflect out into the world that works for peace. That’s what we’re going to need to get through this, and that’s something that a faith community can support and offers, and Quakerism is one of those faith communities that’s doing that at present.

Zack Jackson: Whether we are facing World War III or a fragile peace, the mandate is the same. We need people who know how to weave our common threads back together. I asked Tim what his ultimate hope was. Not a strategy, not a policy, but a dream.

Tim Gee: You know, I have an answer. It’s just, I almost daren’t say it, because it seems so distant from where we are. But I do believe that there’s that of God in everyone. And I also believe that if people see that of God in their neighbor, then they won’t be able to harm them. I also believe that the vast majority of the world’s Christians, and indeed the vast majority of people of faith in the world believe that war is against the will of God. And sometimes I think that asking people to act on that seems too much to ask. And then I catch myself and I wonder, why do I think that’s too much to ask? Surely it should be exactly what we should be asking. So I suppose my dream is that people of faith won’t kill one another or anybody else. For that matter, I think that’s my dream. And I can’t work out if it’s extremely modest or if it’s, you know, wild, beyond our dreams, beyond our imaginations. Maybe it’s both. I wonder if, if listeners to this podcast pray, I might ask that you might pray for such a thing, if that’s a way that you pray, or if the way that you pray is to open your heart and listen, that you might open your heart and listen for what role you might have in This, in this great change that needs to happen.

Zack Jackson

Thank you for listening, and thank you to our guests, Tim Gee, Max Carter and Bridget Moix. For discussion questions and a transcript of today’s episode. Make sure you check out Quakerpodcast.com and while you’re there, be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss a thing. This episode was hosted, produced and edited by me, Zack Jackson, Jon Watts wrote and produced the music. Thee Quaker podcast is a part of The Quaker Project. We are a nonprofit Quaker media organization dedicated to giving Quakerism a platform for the 21st Century. If you like what we’re up to, please consider becoming a monthly supporter. You can go to Quakerpodcast.com and click support in the top right window. It takes less than five minutes, and we really appreciate it. And now your daily Quaker message as read by Susan Majimbo

Susan Majimbo

Margaret fell 1660 we are a people that follow after those things. That make for peace, love and unity. It is our desire that others feet may walk in the same and do deny and bear our testimony against all strife and wars and contentions that come from the last that war in the members, that war in the soul, which we wait for and watch for, in all people and love and desire the good of all.

Zack Jackson

To get Quaker wisdom in your inbox every day, go to dailyquaker.com. That’s dailyquaker.com.

Hosted, produced, and edited by Zack Jackson.

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

This season’s cover art is by Todd Drake

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)