Hope, Humility and Humor from a Bad Quaker

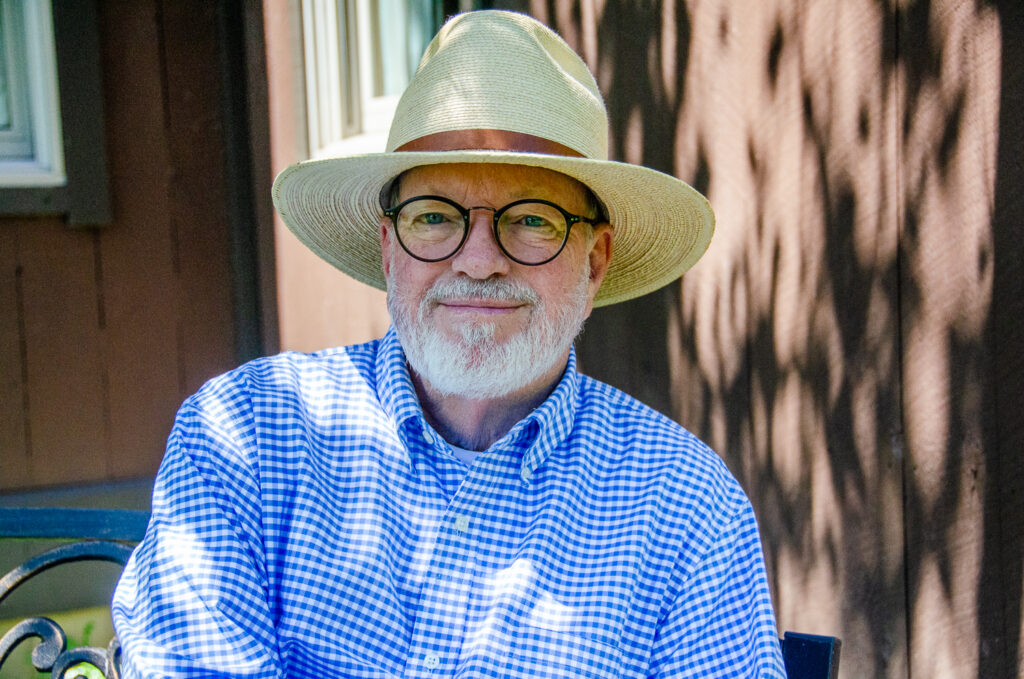

Popular Quaker author Brent Bill has written about prayer, how to live an abundant life, and sacred silence. Considering himself a “fellow traveler” rather than an expert, Brent invites his readers to join him as he explores topics of faith through a Quaker lens.

On this episode, Georgia sits down with Brent to discuss the Christian life, his self-proclaimed status as a “bad Quaker,” and lots more. Join us for this thoughtful and hope-filled conversation.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Have you read Brent’s books? What do you think of this episode? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Download the transcript and discussion questions.

Discussion questions:

- Brent Bill says there’s a danger in alienating others by our approach to activism. How can we be for something and still be agents for justice?

- Brent says many Friends have become biblically illiterate — some because they assume they know what it says, others because they have left it behind because they’ve seen it used as a weapon. What do you think of this assessment?

Brent Bill: We expect the real presence of Christ to be there in the same way the Roman Catholics expect that the host, once lifted up and consecrated, becomes the actual body and blood of Christ, and that’s what silence is for Quakers.

Various: Thee Quaker Podcast: Story, spirit, sound.

Georgia: I’m Georgia Sparling.

Jon: And I’m Jon Watts.

Georgia: And today we’re talking to a self-proclaimed Bad Quaker.

Jon: Alright, I like where this is going so far.

Georgia: Haha, yeah so our guest today is Brent Bill, a midwestern Friend who has been a Methodist and a Quaker pastor and who has written a number of acclaimed books for and about Quakerism and about wrestling with topics of faith, including one slightly controversial book called Confessions of a Bad Quaker.

Jon: So I remember when Brent’s Facebook page “The Association of Bad Friends” was really starting to take off. It’s a collection of humor and self deprecating posts and it’s a refreshing change of pace. There are so many heavy things in the world that Quakers are taking on, it’s nice to have some lightheartedness in there too.

Georgia: Oh yeah. Definitely good to be able to poke fun at yourself. Yeah so back in June, I visited Brent at his home outside of Indianapolis, Indiana where he lives on a stretch of land called Ploughshares Farm. It’s really gorgeous and he’s got this beautiful house made of reclaimed wood. It’s very cozy and Brent and I sat down for this interview in his upstairs study where a lot of his writing takes place and we talked about all kinds of stuff — his Quaker upbringing to the thoughts on the Quaker testimonies, on sacraments, on recognizing the holy in everyday life and of course we had to talk about his new book of short stories called Amity.

Jon: Alright. Sounds jam packed. I look forward to the conversation!

Georgia: Yeah. Let’s go.

Brent: I’m Brent Bill, world famous race car driver.

Georgia: Um, let’s try that again.

Brent: Okey doke, well, I’m Brent Bill, lifelong Quaker. I grew up in the evangelical friends tradition, and then have been here in Indiana for quite a while, but worked, been on the boards of Friends United Meeting, and then worked for Friends General Conference for a number of years. I kind of covered all the Quaker bases in my life. I am a graduate of Wilmington College in Ohio and Earlham School of Religion.

Georgia: Brent has also served as a pastor of Friends meetings and worked for several nonprofits. He and his wife Nancy, who recently passed away, established Ploughshares Farm — 40 acres of Indiana farmland that are being rewilded into tall grass prairie and forest.

Oh and…

Brent: I write the occasional book or two,

Georgia: Actually, by my count, Brent has written 28 books — a mix of genres from nonfiction books for youth books to books on spiritual growth and most recently his first work of short stories. His work is infused with his Christian faith and his Quaker background so I asked him what it was like to grow up in a Quaker household.

Brent: If the meeting was open, we were there. It seemed like, and it was pretty conservative evangelical Christianity with a Quaker tinge, but it was a very loving and caring meeting that we grew up in. And my my parents, especially my father, were very hospitable folks, and so we had traveling ministers staying with us all the time from a wide variety of friends, including overseas friends. Faith was always central to our our growing up, I guess.

Georgia: So, Growing up in a Quaker family, was there ever a question for you as to whether or not you wanted to be a Quaker yourself?

Brent: Oh, sure. And I say I’m both, in the old term, a birthright friend, but I’m also a convinced friend. I did, when I was in college at Wilmington, serve at a United Methodist Church as the associate pastor, as a youth minister, because for one, they paid and had health insurance and all those good things. But it was during that period that that I realized, no, my spiritual home is the Religious Society of Friends.

I’ve always appreciated the various traditions and things that I could learn, but it’s I need to be a Quaker for one, because I’m not always peaceful, silent, simple, treating people equally, and I need those testimonies to call me back to being the person I’d really like to be.

Georgia Sparling: Having worked for a Methodist church, how was it to, like, participate in the sacraments there, whereas, because I’m Baptist, and I grew up in that tradition, and still am part of it, and so to me that the sacraments are so crucial, but then for Quakers, they’re not.

Brent: Well, I would argue the outward sacraments are not important to Quakers, but that the inward reality of those are and so I would so my closest friends, even when I was doing pastoral ministry, were the priests in town, because I always felt like Quakers and Catholics had a much higher view of the sacraments. And some others, but in the Methodist church, I was often gone on Communion Sunday once a quarter.

I see how it is important to people who participate in those rituals, but I also see how it can be just a ritual, in the same way that our silence can just be dead if we don’t come prepared and and really expect that that Christ will be there among us, be present and and be our present teacher in that so both forms can be dead, but we Quakers tend to make fun of other people who have their forms, and I don’t. I don’t think that’s a good thing. I think we should be more respectful of other people’s traditions.

Georgia: Brent grew up as a reader. He was urged by his mother to check out books that went beyond his reading level and he read histories and fiction, humor and the occasional poem.

Brent: Which now I have whole collections, because poetry seems to me to be awful close to prayer. Those who do it well invite us into a very deep and powerful realm, but I mostly read fiction because, yeah, I mean, what one of the first things we we say to those who love us is “tell me a story,” you know, or when we meet somebody, “it’s tell me about yourselves,” not tell me about your your thoughts. It’s like, tell me, tell me you know we and then we launch into a story about you know who we are. So I think story is really powerful, in some ways, more powerful than nonfiction and they’re both powerful, but in different ways. I think story and is one way to tell the truth slant in a way that people can hear it even uncomfortable truths.

Brent: I used to think, and I still do to some level, that writers had to be the most interesting people in the world you know, to come up with these stories or write nonfiction that was compelling to read and and so forth. Now my father was a bit more artistic, and so he he was big into drawing, and so I actually majored in art in college, and took all the art courses I could in high school, and was a fairly good high school water colorist.

When I got to college, I found out I wasn’t as good. It was like moving up to the big leagues. So I switched to photography, and you’ll see camera parts all around here. So art and creativity have always seemed important to me, and I haven’t always been able to articulate it well, as far as the spiritual life, until I had an opportunity a few years ago to really begin thinking about it, and it resulted in a book, of course, when I think deeply about things that usually a book comes out, but Beauty, Truth, Life and Love. And it seems to me that one of the ways we mirror the Divine is in creative spirit and and too often, especially early Friends eschewed the arts, you know, and their creative power, and how that could actually be a spiritual enterprise.

And I think even today, a lot of congregations see art or whatever is nice, but just kind of an add on, instead of encouraging people to to nurture their creative side, whatever that is for them. And so this creating beauty, I think, varies for all of us, but there’s something satisfied, soul satisfying, about working to create beauty that we need to pay more attention to. And so writing and photography, to me are are ways that I feed my spirit, besides the traditional sorts of ways.

Georgia: Brent started pitching articles to magazines in the mid-70s but he says it took three years before he got anything beyond book reviews published.

Brent: I thought I was a better writer than I was when I started out. I’ve got the rejection slips to prove it.

Georgia: By 1984, though, he’d made some headway in his writing and published his first two books.

Brent: One was a rewrite of my master’s thesis on a radical Quaker in the 19th century who was big in the pastoral movement, and also wanted to reintroduce the sacraments to Quakers. And then my second book was on rock and roll to a national publisher, and that was my first general publication that came out.

And I’ve just been writing ever since I wrote a whole series of books for junior high and high school kids, Lunch is My Favorite Subject, Things Your Guidance Counselor Never Told You. So they were light humor, but they had a kind of spiritual point to them, and that was, that was fun.

That took me up to about 1997 or so. And then I did a book called Imagination and Spirit, which is an anthology of modern Quaker writing in about 2003 I think. It was the first book I’d written that got a starred review in Publishers Weekly.

Georgia: Then one day he was driving with an editor friend who had, incidentally, rejected quite a few of his book pitches.

Brent: And we were talking about the Indiana landscape in the fall and we’re just chatting, and I was trying to point out the subtle beauty in autumn of a cornfield that’s been picked, and you can see the general risings and fallings of the land and the way the light was going. And she said, “You see things different, you know, you you see things differently.”

And I said, “Yeah, it’s probably because I’m a photographer.” And she said, “No, it’s, I think it’s because you’re a Quaker and you all pay attention.” And so we started talking about that. By the end of the trip, then we came up with the proposal for the book Holy Silence, and which was my first in a series that probably is sort of still continuing, but trying to make the things of our particular tradition accessible to folks who aren’t Quaker and to say in the way that I’ve learned from other traditions, here are some things you might want to learn about us that you can incorporate into yours. The woman’s name was Lil Copan. Still is Lil Copan, and she helped me find my voice as somebody, not an expert, but as a fellow traveler, and that’s how I try and write.

Georgia: What is the role of of silence and and what has it been in your life?

Brent I don’t think early on I knew as much about how important it was, but I think part of it’s the rhythm, even in a pastoral meeting, it’s the pace, you don’t rush. Do you rush from one thing to the next? Are you leaving space for the Spirit to move and be heard? But it takes a wise pastoral team to be able to do that, and it also in my own ministry. When I was a pastor at a Friends meeting, there were a number of Sundays I didn’t speak because it was just obvious to me, this is, yes, I’ve got it planned, I’m ready to go. But no, something else is happening here. Sit and pay attention to it.

Georgia: Is that a comfortable feeling?

Brent: Well, yes and no. If you’re being paid to be the pastor, you don’t want to do it too often probably. What are we paying that person for? But, but yeah, I think there’s a freedom in it to think, yeah, this is not about me. It is about, do I really have a message from God to share with these people that’s coming from more than my interest in a subject, in my own intellect or whatever. Do I really have something to say that can be helpful? And if I can’t, then to be quiet. Camby Jones once said to me in a class, it was on Quakers, and he goes, you know, “if you can’t improve the silence, keep quiet. Speak, if, only if we can improve the silence.” And I use that to guide me through all my my pastoral work.

Georgia: What role does silence play for you outside of a meeting?

Brent: It’s important. It’s extremely important for me. I mean, I think part of it is that while I teach and lead workshops and speak, actually, I’m kind of an introvert. I need silence because it renews me. And so with all this land, there’s always work that needs to be done. And so I call it tractor time. It’s, it’s silence. I mean, the engine’s roaring, but those are quiet times out in the and I, I do a lot of walking in the woods, and we’re in the prairie, just because I need to get centered. So silence keeps me centered, We can multitask spiritually, if you would. You know we can be, I can be out mowing and still be in a state of of grace in in that sense and renewal.

Georgia: After the break, we’re going to explore what Brent means when he says he’s a bad Quaker and why you might want to be one, too.

Jon Watts: Hey, Becca, it’s Jon Watts. How are you?

Becca Godwin: Hi, I’m doing well.

Jon: You gave us a donation in June of 2023. Thank you so much for your contribution. And you left us a comment that said that you’re quasi Quaker who loves good storytelling. So I was wondering if you could tell me about that. How are you? What does that mean to be a quasi Quaker?

Becca: Yes, so my mother was raised Quaker. Her grandfather became Quaker after his experience in the military. And so we grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, she would take the four of us kids to Meeting. So I was, you know, held as a baby in the Quaker meeting. And then when I moved away, and started living in different cities, I would go, I would go in the different cities that I went, but I never really started going regularly as an adult until last year, when I was living in Nashville. Started going regularly, really got a lot out of it. And then I moved away from Nashville. And I haven’t gone to the local meeting where I live now yet, but I have had the podcast to listen to. And so it’s helped sort of bridge this transition.

Jon: Yeah. Thank you. So. So what was it like to go to Quaker meeting again?

Becca: It reminded me a lot of my experiences when I was younger, just, you know, it’s always a different building, but the what in my experience, there’s always a similar kind of energy and calmness As that just radiates from these from these spaces. I think in that first one back, there weren’t any messages even given. But I still just felt the sense of like, Ah, yes, this is good. This is what this is what a part of me has been searching for and, and desiring.

So in the end of 2022, I stopped drinking. And in January 2023 is when I started going to a meeting in Nashville. And I sort of joke that I didn’t start going to AA, but I started going to Quaker meeting. And someone there happened to also start sharing messages about their experience in recovery. And so it was really, it really was helpful for me during that time where I felt like it was important to to have something that was sort of soul satisfying, but uniquely for me. Yeah.

Jon: Yeah, what happens for you in that, in that hour of silence?

Becca: It oftentimes feels like a circus is happening in my head, but it’s the circus that would be happening anyway. And I’m just actually able to, to let it play and let it run in a space where I feel anchored by the presence of the other people that are there.

Quakerism has is part of my family’s story. And as much as people talk about it, within my family, I think there’s always still this sense of like, mystery or intrigue around it, you can talk about it as much as you want. And it still feels like this, this thing that’s different than almost anything else in my life anyway. It’s just not quite containable. And so listening to the podcast helps give some some depth to these like intangible things that I’ve that I’ve always heard and felt and provide some context.

Jon: So I wonder if you have any advice for us in in making, you know, season two of the of the podcast.

Becca: I mean, not really, just to keep doing what you’re doing. When I heard that this podcast would be coming out. I was like, oh, man, this is either going to be like really, really good. Or it’s going to struggle. And just, I mean, that’s the case with most podcasts in general. And but I was really like hoping and pulling for this one to be in that really good category, and it has exceeded what I was hoping for.

Jon: Thank you.

If you’re like Becca, and you’re hoping and pulling for this podcast to be the best Quaker podcast it can be then we could really use your support. Thee Quaker Podcast is listener supported. And by our calculations, just over 3 percent of you are monthly supporters and we’re so appreciative of that. We would really like to see that number continue to grow so that we can continue to make it for many many more seasons. So if you’re one of the 4,000 or so folks this month who are tuning in but you haven’t quite made it yet to QuakerPodcast.com/Support please do. It would mean a lot to us and to listeners like Becca. Thank you. And back to the show.

Georgia: Let’s talk about Life Lessons from a Bad Quaker. Yeah. Okay, the title is great. What does that mean to be a bad Quaker?

Brent: And I was working on a book on on Quakerism in general. You know, I’d done silence, I’d done discernment, but I thought I’d like to do one on the testimonies, you know about simplicity, peace, etc, as a whole, as a unified way of looking at how Quakers live out their understanding of of the good news in the light of Christ and so I was working with Lil. She goes, “could you write the smart ass guide to Quakerism within limits?” And I go, “Well, that would be fun. And so that’s how Life Lessons from a Bad Quaker came about.”

Georgia: Brent said before he wrote the book, there had been a lot of conversation in the Quaker world about what it meant to be a bad Quaker and he and some friends came up with the idea for the Association of Bad Friends.

Brent: You had to self nominate to be a member, nobody else could name you a bad Friend. You had to name yourself. And so it was going to be a humor site. It’s still on Facebook. It has like 9,000 members now, well, we just kind of started as a joke to say, none of us measure up. If want to use the Bible verse “For all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God.”

Brent: You know, all Quakers have sinned and fall short of the glory of Fox. I don’t know. You know, we just, we’re just not always very good at being good.

Georgia: With the book, Brent says:

Brent: I wanted to be humorous in some ways, like the Facebook site, but also personally confessional about my own shortcomings and living these out, but then Quaker moments, you know of when we failed those testimonies and just using humor to deflate our pomposity a bit, because we do so much self praise at times about how we’ve gotten everything right. Well, we we’ve screwed up an awful lot at times, and and so, and we will continue to and but that doesn’t make the testimonies any less valuable or helpful, because if we didn’t have them, we’d be even worse than we are now.

It’s how those things have to be relevant in the living of our daily life, not just big ideas.

I’ve met some friends who are very ardent anti-racism or anti-war, but the way they’re approached, it’s so strident, it’s unattractive, and they often mirror the thing that they’re against. And so trying to think, How can we be for something, and how can we be positive and start working on our individual life instead of, I can’t be a real work for peace if I’m so angry and distraught all the time. So how do I learn to carry peace in daily life? So that’s how, that’s how Life Lessons came about.

Georgia: The book has been popular but not with everyone.

Brent: Some found it a little too smart assy, and I said, You should have seen the original draft, because the publisher toned it down, and others thought it was a little too flip, yeah? But I mean, I think there that certain deflation we Quakers need, at times and and other people do too to realize, okay, we’re most of us aren’t very good at being good.

Georgia: You’re writing books that have a spiritual perspective, but like, what is, how is it working on you when you’re when you’re writing books on silence and prayer?

Brent: Well, as I sort of alluded to, I get to write about things I’m not very good at, and I need to try and explore more, like the books on prayer. You know, it works on me by thinking, help me sit down and go so, what is prayer? What’s it? What does it change God’s mind? Or does it change me? Or both, or and so, to begin to wrestle with some of those questions, not as to write a theology book as I’m really not interested in anymore. When I was younger, I was theological debates. You know, if you want to argue theology. I don’t really care. I want to know more how does this help me live my days? How does this help me be a spiritual person in this world and be a person of light, instead of a argumentative old grump? Which I could be easily so I really get to wrestles with it and think about, okay, now, if I’m feeling this way, other people might be feeling this way, and so how can I invite them into the conversation about what prayer is for them and how to how to make it more real for them, like I want it to be more real for me, or the same with discernment or silence, how you know, and the first title for Holy Silence was actually Sacramental Silence.

The publisher, though, wouldn’t buy that. So, because the more I thought about it, I thought that that is what it is for us. We expect the real presence of Christ to be there in the same way the Roman Catholics expect that the host, once lifted up and consecrated, becomes the actual body and blood of Christ, and that’s what silence is for Quakers. It’s not, it’s not the silence that’s worshiped. You know, when we do it right, it is we’re finally attuned, individually and as a group to Christ as our present teacher, even now, and experience that deep communion.

Georgia: Brent’s books are explicitly Christian and I asked him how the Bible has been part of his spiritual growth.

Brent: Certainly my growing up evangelical has left me fairly well versed in the Bible, plus going to Wilmington College of religious school, you know, and taking Bible there and going to Earlham School of Religion, and taking Bible there and spending a semester at a Lutheran seminary, taking Old Testament there,which was an experience. So I think the Bible has a lot to offer is and that Friends are in danger of becoming biblically illiterate because they’re allergic to how it’s been used by others as as a weapon, instead of really reading it themselves and seeing what’s in there and saying, Okay, well, I, I need to wrestle with this part. Or, you know, I that doesn’t ring true for me, but not just dismiss it out of hand. What are what’s in there to say?

Georgia: So do you feel that is true of evangelical Quakers?

Brent: I think it almost as much as liberal friends, although more evangelicals study it a bit more, but so many of them still just make assumptions about it because they learned it in Sunday school as kids and haven’t gone on to wrestle with it as adults. What’s it say to me, not just what’s what are the words on paper? The Bible is supposed to be instructional for faith. What’s it instructing us on? You know, what’s, what’s, what’s this all about? And I don’t think enough of our pastoral Friends do that, but then too many of our unprogrammed Friends just dismiss the Bible completely out of hand, and so never pick it up and look at what it really says.

Georgia: but let’s talk about Amity. So yeah, that’s your most recent book, and it’s your first book of short stories. What? What led you in this direction?

Brent: Well, I’ve always wanted to do short stories, and indeed, some of those stories were first written about 25 years ago.

Georgia: The book’s themes include family relationships, forgiveness, reconciliation, and belonging and have a dose of humor. In one story titled “Places to Go,” a 1930s housewife determines to teach herself to drive, something sparked by his own grandmother’s story. In “The Funeral,” a family gathers to process an unexpected death.

But the book opens with, “A Trip to Amity” — and there is a spoiler here so speed ahead a minute if you need to — but anyway in the first story, a Quaker preacher is scheduled to fill in at a church in the fictional midwestern town of Amity, but his wife has, as often happens, made him late and the tension is thick as they drive to the church. Upon arriving, the preacher rushes and takes his seat on the bench in the pulpit. Then…his wife realizes they’re in the wrong church and silently alerts her husband. The church, incidentally, is not even Quaker, and the couple explodes into laughter when they get back in their car.

Brent: I used to write a blog called Holy Ordinary, that the ordinary things of life are the most holy that there is. There is grace all around us, if we will look for it and want to experience it. And sometimes it comes gently, like dew drops, and other times it’s a kick in the in the butt, like what happens to the guy in the first story. It’s like, you know, he’s missed all the grace of that day until that moment, and, yeah, and it’s the person he’s been maddest at that reveals the grace. Yeah, it humbles him, but not belittles him. She doesn’t do unto him what he has done unto her in some ways. She’s the bigger person, so. But I think that that that’s it is just the the holy, holy ordinary that surrounds us all the time.

Georgia: So kind of going back to Quakerism, what is making you hopeful about Quakers today?

Brent: Well, young adult Friends certainly are folks who are doing good things, you know, like Jon and and Quaker Voluntary Service and other just young Friends, Katrina McQuail and her organic farm up in Ontario. Cherice Boc is doing really great stuff. She has a PhD. Wes Daniels down at the, you know, Quaker Center at Guilford. So there’s lots of good things going on.

What concerns me still is how hidebound I think we are and ancestor worshippy we are. We talk too much about the good old days instead of or or the bad old days, and how we failed, instead of trying to say what’s what’s Spirit calling us to do now? And 100 years from now, we’ll be judged and probably found wanting as well. We are products of our culture as well. So instead of trying to become the perfect Society of Friends before we start telling the good news, to think that we will ever eliminate sexism, genderism, racism, completely, while noble, that’s not going to happen even in our own lives.

We’re products of our time. We’re works in progress. We need to say, how can we be an inclusive society? How can we get people not to join us, but to see this as a good spiritual path, and realize that with each person who joins a religious Society of Friends today, it changes and it changes us, and that’s what we need. And the early Friends movement certainly got changed by those who joined it, and they expected to be changed people and to change society. Too often we don’t expect to be changed, and we’re resistant to the change. So how can we get to a place of changeability, not for the sake of getting butts in the bench or to fill a committee, but because we have something that is universally helpful to People, if we would learn to be open and express it in an invitational and caring way, and say, Come, let’s walk together, and that would give me hope. I see more of that in younger generations than a lot of people my age, and especially in newer meetings than older meetings, who are too, too bound to a place, a building even.

Georgia: How would you describe the season of life that you’re in right now?

Brent: Probably autumn, moving towards winter. Now, I have to admit, autumn has always been one of my favorite seasons, the light, the color, the slanting shadows and stuff that help you see things you wouldn’t see otherwise, when the light comes through. And also it’s slower. And so I do find myself as a formerly pretty much driven type A personality, living into a quieter, more contemplative period and enjoying it. I mean, I’m not ready, although right now, you know, winter is around me, so I appreciating every day for itself, instead of always planning for the future and also saying what’s important for me to say yes to and what’s important for me to say no to, and there are a lot more no’s at this point to just say that would be fun, but that’s that’s not mine to do anymore, so it’s a good place for me.

Georgia: Thank you

Brent: Sure

Georgia: I appreciate um, yeah, just letting me come in and being one of the yeses that you’re able to do. So I really appreciate that.

Brent: Oh, it’s my pleasure.

Georgia: Thank you for listening and thank you to our guest Brent Bill. Brent is the author of a number of books, including Holy Silence: The Gift of Quaker Spirituality; Beauty, Truth, Life, and Love: Four Essentials for the Abundant Life; Life Lessons from a Bad Quaker; and Amity: Stories from the Heartland.

Please visit our website, QuakerPodcast.com for a transcript and discussion questions for today’s episode.

This episode was reported and written by me, Georgia Sparling. Jon Watts cohosted and wrote and performed the music. Studio D mixed the episode and your moment of Quaker Zen will be read by Grace Gonglewski.

If you’ve been holding off on becoming a monthly supporter of Thee Quaker Podcast, why not consider it now? You can begin giving at just $5 a month and it only takes about 5 minutes to sign up! Just head to QuakerPodcast.com and click Support at the top of the page.

And now for your moment of Quaker Zen.

Grace Gonglewski: Our principle is, and our practices have always been, to seek peace, and ensue it, and to follow after righteousness and the knowledge of God, seeking the good and welfare, and doing that which tends to the peace of all.

Georgia: Sign up for daily or weekly Quaker wisdom to accompany you on your spiritual path. Just go to DailyQuaker.com. That’s DailyQuaker.com.

Recorded, written, and edited by Georgia Sparling. Co-hosted by Jon Watts.

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Mixed and mastered by Studio D.

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Referenced in this episode:

- Learn more about our guest Brent Bill and find a list of his books.