Quakers and the Internet

We’ve got three stories about Quakers and communication — from pre-Internet to social media.

Join us as we explore the Twitter of the 17th century, the ways that modern Quakers can take a cue from fandom, and how TikTok has given one new Quaker a way to express her faith.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Share your thoughts with us. Leave us a voicemail at 215-278-9411 and let us know what “conscientious objector” means to you.

Here is a list of books and resources:

- Print Culture and the Early Quakers by Kate Peters

- A Convergent Model of Renewal: Remixing the Quaker Tradition in a Participatory Culture by C. Wess Daniels

Do you interact with Quakers and faith communities online? How have those interactions influenced your own spiritual journey?

What do you think about Wess’s idea of remix culture?

Share your thoughts below!

Jon Watts

If you want to get your message out in the world today, you’ve got to post it somewhere on Twitter or Facebook, or whatever, but if you want to get your message out in the 1600s, you print a pamphlet.

Kate Peters

They’re a bit like the internet now in that something happens, somebody can write a pamphlet about it. You can have it circulated within a few days, sometimes within a few hours. And they’re very light. They travel across the country very quickly. And that’s what that’s what people said about the Quakers that their pamphlets are flying as thick as moths up and down the country that they’re everywhere.

Jon Watts

Today, we’re talking about communication, specifically, how Quakers have embraced modern forms of communication in the past. And how Friends struggling to find a place in the age of the internet might take some cues from the 17th century.

Various

Thee thee thee thee thee Quaker podcast: story, spirit sound.

Jon Watts

I’m Jon Watts.

Georgia Sparling

I’m Georgia Sparling.

Jon Watts

So Georgia.

Georgia Sparling

Yes?

Jon Watts

It’s, it’s episode three. You know, how’s, how’s it going?

Georgia Sparling

Pretty good. I’m a little tired.

Jon Watts

Well, well, maybe it’s time to give you a little break the, the – loved the last two episodes. Thanks so much for your work on this.

Georgia Sparling

Thank you.

Jon Watts

Maybe, uh, maybe I can try one.

Georgia Sparling

I am very happy to hand the mic over to you. So what are we talking about today?

Jon Watts

Well, so it’s episode three. Our last two episodes were about the big picture with Quakerism. Getting a sense of what it looks like today and how it all started. Today, I was thinking we could do something maybe a little different.

Georgia Sparling

Okay, like…?

Jon Watts

Well, since this is a podcast, and you’re probably listening to it on your phone, or through a website, and since we are a brand new 21st century online media startup, I thought we could like, I don’t know, talk about it.

Georgia Sparling

Like, talk about the organization?

Jon Watts

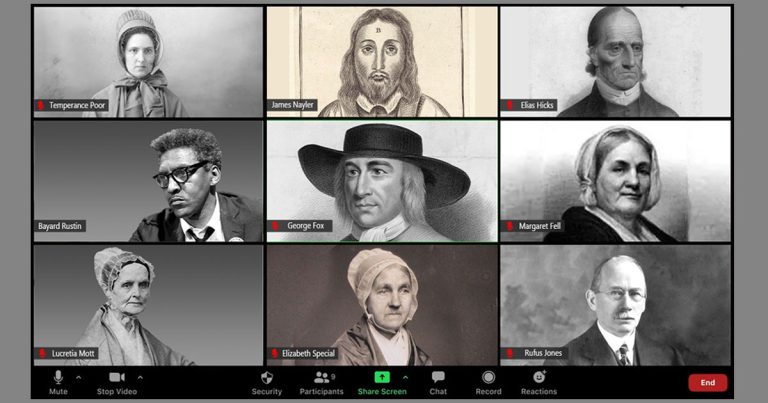

No. Well, I mean that it’s not unrelated, but like, you know, what is this radical shift in communications technology that we’re experiencing in our lifetime. I mean, when I was growing up, it blew all of our minds that you could dial up a chat room and talk to someone from another continent. And now we have Facebook and Twitter and YouTube and TikTok, and they’re all in our pockets all the time. So how is this changing life as we know it? How are Quakers in particular coping orresponding to these changes? And like, you know, I don’t know, what would George Fox do?

Georgia Sparling

WWGFD?

Jon Watts

Yeah, that’s right. WWGFD

Georgia Sparling

Sounds like a cuss word. Okay, cool. So like modern Quakers and social media?

Jon Watts

Yeah. Or we’ll get there. So today, we have some rich stories with modern friends who are thinking about social media in innovative ways. But I actually wanted to start by looking backward. Like, is there a precedent for this? You know, as I was joking about WWGFD, being a thing at all, but really like the early Quakers had to answer this question too. The world is rapidly changing around us in really chaotic and unpredictable ways. And it’s partially fueled by this escalating innovation in communication technology. So, you know, does that remind you of anything?

Georgia Sparling

I’m honestly just sitting here wondering what George Fox would tweet.

Jon Watts

Yeah, that’s exactly it. You know, in 1650s England the early Quakers did have something that was like their own version of Twitter.

Georgia Sparling

Okay, so like the printing press. Yeah,

Jon Watts

Exactly. So that’s something I don’t actually know a ton about, but I did get to talk to someone recently, who does.

Kate Peters

So it comes out of their preaching and Quaker preaching is very spontaneous. So you preach, you sp- learn- you didn’t call it preaching though, you called it speaking as they move to the Lord. So the printing actually comes out of wanting to keep the itinerant ministers wanting to keep in touch with groups of Quakers they’ve come across, or to reinforce the message of their preaching.

Jon Watts

That’s Kate Peters, historian, who lives in Cambridge, England.

Kate Peters

And a long time ago now, I studied for a PhD in history. Also at Cambridge University and I was a PhD on Quaker pamphleteering. I was interested in women’s history, looking at the English Revolution because women became very active participants of the revolution. And the most active participants of all were Quakers. And they wrote fantastic pamphlets and I obviously came across Margaret Fell’s pamphlet that was “Women’s Speaking Justified” that was justifying the rights of women to preach. I thought that was fantastic. So I had done an undergraduate dissertation on Quaker women’s writing, and had a niggling question at the end of it, which is that I’ve only looked at the writings by women.

Jon Watts

So I first came across Kate’s paper, “Print Culture and the Early Quakers,” back in 2011. When I first had the idea to compare the printing press to the internet, I really thought that I had come up with that connection. And I thought that I was so clever. But after reading Kate’s paper, I realized there was a lot that I didn’t know, and also that I was far from the first person to make this comparison. In fact, early Quakers are widely known both in Quaker circles and outside of Quaker circles for their enthusiastic and strategic use of the pamphlet. Now, I’ll admit that pamphlets do not sound all that sexy, but they had this potential to reach 1000s of people at a time when communication was much, much slower. But technically speaking, what is a pamphlet?

Kate Peters

Yeah, so a pamphlet is a small book, a very small, cheap book that’s made of one large sheet of printing paper. So they printed about eight pages on either side of that large piece of paper. And they fold it up in the clever way, and slit the pages and stitch it together.

Jon Watts

Pamphleteering had a sort of democratizing impact, because it was so affordable.

Kate Peters

It’s quite cheap to produce, I think it costs about a penny. So most people can afford to buy a pamphlet. And because it was, you know, it’s very quick to produce. It’s not like that, you know, big heavy volumes are very learned works that take a long time and a lot of labor, a lot of money to produce. They can do these late at night, they can do them very quickly. And it’s really the bread and butter of the printing industry from the early 17th century onwards.

Jon Watts

Pamphlets were also more responsive than previous forms of printing,

Kate Peters

They’re very contemporary, so they’re responding to everyday events. And they’re a bit like the internet now in that something happens, somebody can write a pamphlet about it. You can have it circulated within a few days, sometimes within a few hours.

Jon Watts

So the whole country is experiencing this time of tremendous upheaval. A civil war ends with the execution of the king and ushers in a period of religious toleration, where suddenly, anyone with access to a printing press, can print whatever they want, no holds barred. Lots of groups jump on to the opportunity to get the word out about their theology. But the Quakers stood out.

Kate Peters

Where the Quakers are interesting, I think, in that model, is that they’re quite young, they’re young men, they’re in their early 20s, and they’re young women as well. So it means that they’ve grown up in that, a bit like teenagers now with the internet, they’ve grown- that’s all they’ve known. These are these are young men who have known printing as a mode of communication. Since they were young. That’s that’s what they’ve seen. So they’re very savvy about how they’re going to use prints. So if we think about how long it’s taken, you know, Puritans to start using print polemically, the Quakers do within a couple of weeks, hey, presto, off they go.

Jon Watts

So I asked Kate, you know, what motivated early Quakers to publish so prolifically? And what was strategic about their publishing?

Kate Peters

So I think it’s, if we think about the significance of pamphleteering up until that point. Quakers are doing the same thing with their with their pamphlets, bringing their message of the universal light of Christ being within everybody. That’s not a straightforward message to give to people in 1652 or 1653. So many people will will find difficulties with that. One of the difficulties is, is this blasphemy? Are they claiming that they, that they are actually, they have Christ within them or that they are Christ? So it’s not possible for Quakers to preach their message without getting into trouble. And I think that they are not exactly keen to get into trouble but they’re not frightened to get into trouble. And they want to have the argument about whether or not what they’re saying is blasphemy. And not only that, but they want to know, on what grounds they’re being challenged. So what is the legal basis for you to say that that is blasphemous?

Jon Watts

For those early Quakers pamphlets were not only a crucial way for them to share their ideas, but also to call into question the legal legitimacy of the claims against them.

Kate Peters

What legitimacy does somebody have to tell me I can’t say that, because I’m saying this from God. So this is my prophecy. So it’s it is a proper theological dispute that they’re having, at every level. So it’s very, very localized, it will be with the people of Under Barrow. It will be with ministers in churches; they’ll walk into a church, and they’ll say, By what authority do you preach? And it’s an important question. You know, is the authority from parliament? Is that right? Should it, should a secular magistrate have the right to determine how people should worship? If they’re challenging a minister of religion who has ordained that minister? Is it a bishop? Is that okay? So, so, so they’re absolutely challenging the authority of ministers of religion, of justices of the peace, who might have arrested them, to say, what’s, what is the basis of your authority to do that?

Jon Watts

And not unlike social media strategists today, the early Quakers used pamphlets strategically distributing them at times and places where it would have the highest impact.

Kate Peters

Okay, there’s a trial going on, we’ll get some pamphlets there, okay, there’s a parliament being called we’re all going to meet there with a lot of pamphlets. There’s a there’s a minister in Under Barrow, who’s giving us, you know, a hard time, we’re gonna go and call him out. So you can see on the scale of it, it’s not accidental. They know they know where to go. They know who their audiences are. It is strategic, and they’ve got an argument to have about whether the government is upholding its promises for and enabling liberty of conscience and the protection of people in their worship. That’s what they want.

Jon Watts

After the break modern Quakers and remix culture, and what happens when you’re brand new to Quakerism, and hundreds of strangers start asking you about it on Tik Tok.

Georgia Sparling

Hi, everybody, it’s Georgia. Again, I just wanted to come on briefly and say a little bit about how much I’ve enjoyed working on this podcast. I know, I know, we’re only on episode three. But this show has come about after months of research and interviewing, editing, discussing. And that’s to say nothing of all the work that Jon and our board have done to get the project off the ground. I have to say, it’s been a lot of work.

But it’s also been so gratifying to put this podcast together and to see it actually go out into the world. I love that it’s making space for more engagement with Quakers and Quakerism. And I’ve also personally learned so much already. And I’ve had so many powerful conversations during my time at the Quaker podcast, I’m really looking forward to bringing some of these really rich, thoughtful, challenging conversations to your ears soon.

And as we continue to report on and share these stories, I want to ask you to consider becoming a monthly supporter of our work, your donation of $10 or $20, a month or more, if you’re able, will go a long way to helping us tell expansive and transformative stories. To learn more about how you can give and be a part of this important project, visit theequaker.org. That’s theequaker.org.

Jon Watts

Welcome back. So we know that our spiritual ancestors, the folks who sparked the beginning of this tradition, we’re living through times that were similar to ours now, there was political upheaval, apocalypticism and rapidly changing technology. And we know that early Quakers were young, technologically savvy, passionate communicators. So let’s talk about that. Where are we? 400 years later? Did we inherit any of that spiritual DNA? So for this next segment, I’d like to bring Georgia back in. Hey, so you told me about a conversation that you had with Wess Daniels, who wrote a book that’s pretty relevant to this conversation?

Georgia Sparling

Yeah. So a few months ago, I met up with Wess at Guilford College where he teaches and we had a conversation about renewal and remix culture, and how it could pertain to Quakers today. And so like Wess in his book says that Quakers are uniquely positioned in our culture to reformulate the movement in ways that might bring about renewal. And I thought this is a really relevant conversation for today’s episode, because so much of that is happening on the internet. Now, here’s what he had to say.

Wess Daniels

So participatory culture is a way of talking about, kind of, a subset of culture today, where you have, it’s essentially talking about fandom, easy fandoms to talk about are, you know, Star Wars, Star Trek, those sorts of things. Harry Potter, you know, which is losing losing ground for obvious reasons, but, but those kinds of fandoms, where you have a group of people who have, you know, texts that they love, whether those are actual texts or movies, and then you have, you know, ways in which people live out their fandom, whether it’s the way they dress, or groups that they hang out in.

And so fandom to me, and participatory culture, was a place where I saw in a non-spiritual kind of secular example, or space, I guess what I’m trying to say, people taking very seriously their tradition, but then doing new things with it. When I was working on this, Harry Potter was very big, and JK Rowling hadn’t quite, you know, ostracized herself from the rest of the world.

But, you know, at that time, especially in the like, mid 2000s, you had bulletin boards being created and websites where Harry Potter fans who were like 12, and 13, and 14 are writing like 50,000 word fanfictions for fun, and then editing it peer reviewing them, and, you know, and there’s communities. And it’s like, okay, how often do you see 13 and 14 year olds, peer reviewing 25,000 word essays for fun? What is happening there that we have a hard time getting folks to show up for an hour on Sunday morning to Quaker meeting?

So something is connecting and working here that is being missed over here? And what I want to know what that is, I want to learn from that. So when I said that, you know, what does culture have to teach us? That’s kind of what I’m talking about. I realized that, kind of, through all of this, a big, word, and a big, sort of, analogy for me is the idea of remix.

Remix has existed forever. I mean, remix is evolution, and our DNA is constantly being remix. But the word remix comes out of hip hop culture and, you know, DJs sampling different tracks and beats. And in hip hop culture and remix you’re doing that to pay homage to the past, while making it new again and relevant. And that, to me, is renewal. There’s something about the tradition that’s still alive, that still speaks. But it needs to be brought into a new context, a new song, a new situation that enlivens it.

And in a way, that’s the whole process by which we need to think about renewal.

You know, a thing with remix is it can really upset people because it’s like, you can’t do that with Marvin Gaye, or whatever, you know, like you have to just keep it pristine and in that we’re going to listen to it the way that he intended and that’s it, you know, and remix says, No, it’s too important to just leave it there. Like we want to make something with it. We want to show how it is relevant or not relevant to us. You know, so there’s that kind of traditionalism of like keeping things where they are and not changing them.

You know, we get we get stuck with an idea of what a Quaker is. We get stuck with who can be a Quaker, who isn’t a Quaker, you know, we get into that kind of copyright essentially, who’s breaking the Quaker copyright. And remix really has no interest in copyright. You know, and, but on the other side, you have this thing, which says that tradition isn’t important at all. I see tradition as alive and evolving, and wanting to learn from it and draw on it, but also be willing to change it and adapt it.

We talk with our students about being apprentices to the Quaker tradition, that’s actually what we mean, learn the tradition and master it, you know, as, as best as you can, so that you can go on to change it, to adapt it to renew it in your culture, your communities that you go into. But both of those are important.

And if, if you can have, you know, Comicon, show up and have 10s of 1000s of people who, like, truly, I mean, it might seem ridiculous to think about this way, but truly know their tradition. But then there, they have also then taken it and applied it to their own lives. They’ve built community around it.

That’s what I’m trying to do and also look for inQuaker communities, not how well have you done at not – absolutely not – changing whatsoever in the last 100 years but like, what are the rules that you’re breaking, because it’s bringing about new life? If we want to invite new people in to those communities, we’re going to have to find ways to help them relate to those stories, to those practices. That’s how we keep our communities moving.

Jon Watts

Thanks so much for sharing that Georgia. I love how Wess is lifting up something that sometimes we struggle with as friends, but it’s also one of our main strengths, which is that this is a decentralized religion. So it’s really up to all of us to learn, understand, and then update the tradition. Like if we say that authority comes from the Spirit, and not from the structure of the church, and we really believe that then it’s on us collectively to figure out where it goes from here. That’s both exciting, and sometimes it can be a little terrifying.

Georgia Sparling

Well, and I think that the internet and social media really create a fertile ground for this remix culture. And that both creates places for community and opportunities for collaboration and dialogue.

Jon Watts

Right? Like, I love that feature on TikTok that lets you like do that with someone else’s video.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, totally. Okay, so what’s next?

Jon Watts

Okay, so I’ve got one last story for today’s episode, and I’m super excited about it. It all starts with this email that I got.

Georgia Sparling

Tell me more.

Jon Watts

Okay, so this just happened like a week ago. So I had been thinking about what I wanted to do for this episode about Quakers and the internet. And then I get this email totally out of the blue. And it’s like this amazing and thoughtful piece of writing and so on point. So this is from Julia, who is a friend in Vermont, and I just want to read you a few lines of it.

Alright, so Julia says, Greetings friend. I’ve only just started to immerse myself in Quaker faith and culture in the last year. But throughout my convincement, I have shared bits of my personal faith journey on Tik Tok. I was quite surprised by how many people reached out in comments and messages. And what I find most surprising is how many people reached out with significant interest on what Quakerism is and how they can get involved.

Jon Watts

She goes on to say, I don’t quite feel I’m the best person to answer questions on the Society of Friends since I’m still in my own learning phase. What I do know, though, is that there’s a spiritual hunger among so many of the people who have reached out to me folks are drawn to the little that I’ve shared about Quakers, and most of those folks are under 25.

Let’s see, finally, just want to read you this one last part. In my generation, social media is not just a form of communication, but it’s also a platform for art community building conversation and change. I have seen this change, spark and grow through so many different movements. I want to navigate the intersection of social media and the Society of Friends. But to be honest, I have no idea where to start. I love your work. I thought who better to ask about Quakers and social media than Jon Watts.

Georgia Sparling

Wow, that’s great. So did you get to talk to Julia?

Jon Watts

I mean, yeah. Julia, I’m so glad to be here talking with you today. Thanks so much for making time for the conversation. I was really excited to get this email from you.

Julia Garcia

Thank you so much for having me. It’s great to be here.

Jon Watts

Yeah. So I’m I’m psyched to get into some of these deep questions that you’re asking. But I wonder if we could start with a brief introduction?

Julia Garcia

Sure. So I’m Julia. I live in Central Vermont. I moved there recently, actually. So I go to the Plainfield Friends Meeting in Plainfield, Vermont. It’s a lovely little meeting house in the woods by river, and I adore it. And I feel so lucky to be here.

Jon Watts

Lovely. Um, so I wonder if you could start by talking a little bit about social media. How did you get into TikTok? And what happened when you started posting videos about Quakerism?

Julia Garcia

Sure. So I’ve had the TikTok account that I have now for almost a year now. And that’s where I really found the chronic illness and disability community. As someone who has chronic illness and is disabled, there’s so much amazing advocacy and activism, and community building that happens on social media for these communities. So I joined TikTok, and started posting about my own journey with chronic illness and disability activism and autism spectrum disorder and all sorts of different topics.

And every now and then I’ve, like, mentioned something about Quakerism, or posted a video here or there. But what led me to email you, Jon, was that I posted a couple of videos in a row about Quakerism. And got so many responses from people saying, I’m really interested in this, how do I get involved? I had someone message me and say, I went to a Quaker meeting after I saw your video, which feels like an enormous amount of power on me. I’m like, I’m not trying to convince anyone to do anything. And now people are reaching out saying they’ve, like, gone in their own communities and gone to like, a religious meeting. Like that feels like crazy to me.

Jon Watts

Yeah, well, I can relate to that, you know, both the sense of power and responsibility around it. So what’s, what’s the lesson there for you? Like, what have you learned from that experience? And what can Quakers learn from it?

Julia Garcia

I think lots of people view the internet and real life as these separate entities. And I think that downplays like the extreme power that the internet has on people’s actions. And like, we’re seeing this through a lot of social movements. And I think that, like when I look at the early Friends that, oh, they were badass like and like, like, they weren’t, like, they were not docile. They were not like, Yeah, I’m just gonna putz around and like, sit in the corner and be quiet. They were just like, No, I’m not calling you, “Sir,” get out of here. And like, they’re like, and I think that we need a little bit more of that energy of that, like, Spirit that incites change.

Jon Watts

Right. I think the I think of the early Friends who were actually, as we’ve just learned quite young, and who were perhaps using the printing press in ways that confounded older generations. But as you said, they they didn’t hesitate. So like, what’s the modern equivalent? Or where do you see the Spirit showing up when we’re talking about social media?

Julia Garcia

I think that is, it would be easy to view social media as a tool. But I think it’s more of a medium or like an expression, where I don’t think it’s like something that we need to have a specific calculated path of how to use it correctly. I think we need to express ourselves through it, and that’s using it correctly. I think that just like some people stand up in meeting and sing instead of speak, I think we can film or speak online or play music or edit weird things together, or whatever it is. And I think that that can be the Spirit speaking through us too.

In the same way that the, what, what you say, after at the end of meeting might hold more gravity in your heart than what you say before meeting starts, I think that when we use social media, spiritually, it can have its own power in the world and impact other people’s lives. And that I’ve had people come to me and for non Quaker related reasons, I’ve had people say, hey, because you said that thing about your chronic illness, I mentioned to my doctor that this is something I wanted to look into. It turns out I have this and I’m on a medication that makes it better.

Like, that’s just like material change that helps people’s lives. And I think that when we communicate with each other, especially in such vast numbers in the internet, like we’re meeting so many more people than we ever would in person. And I think that that, where else do you find the Spirit? Then in meeting hundreds of people you never thought you would? I don’t know. It’s big. I think it’s scary. And I think that we should be a little bit scared of it because it, we don’t know a lot about, like, the internet and the way it’s going to impact humanity long term. But I think it’s part of humanity and a part of the way humanity is expressing ourselves. And that’s where we find the Spirit, so I do think we could find it online.

Georgia Sparling

Thanks for listening. We’d love to know what you think about Quakers and social media and the internet. Head over to our website to share your thoughts. That’s Quaker podcast.com. And while you’re there, you can also read a transcript from this episode, and don’t forget to subscribe.

This episode was produced by Jon Watts and me Georgia Sparling. Jon also wrote the music for this episode. Thee Quaker Podcast is a part of Thee Quaker Project, a brand new Quaker media organization whose focus is on lifting up voices of spiritual courage and giving Quakers a platform and 21st Century Media.

If you want to support our work, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter. We’re a brand new project and every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way. We make this show for you. So thank you for listening.

Now that you’ve heard from us, it’s time for us to hear from you. Tell us what it means to you to be a conscientious objector. Please give us a call and leave a voicemail at this number. You ready? 215-278-8411 That’s 215-278-8411. Please try to keep it to a minute and we might share your response on a future episode.

Thee Quaker Podcast is taking a week off but when we come back, we’re going to talk a little bit about Quaker worship and how deep listening can lead to this whole other thing: vocal ministry.

Recorded and produced by Jon Watts and Georgia Sparling

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Thank you to Julia Garcia, Kate Peters and Wess Daniels for speaking with us on this episode.

I don’t speak English fluid, but I try… I want to learn more and more about Quakers. I helped to former the Havana Group, and my family appear like the first Quakers in Cuba…

I was Quaker attender in Philathelphia some time… Now I live in St Petersburg, Florida. Congratulation about your Qukaer Podcast Project.

I enjoyed your podcast.

Your phone number on this website is not the same as the podcaster says at the end. Should it be 215-278-9411 OR 215-278-8411? Thank you.

Hi Anna – Sorry for the confusion. It’s 215-278-9411.