Quakers and Poetry: Two Friends Share Their Love of Verse

On your phone? Listen on a podcast app:

April is National Poetry Month in the US, and we’re celebrating with an episode on Quakers and poetry. We know many people love poetry, but it can also feel opaque. So, we called up two Friends who have found a home both in Quakerism and in verse.

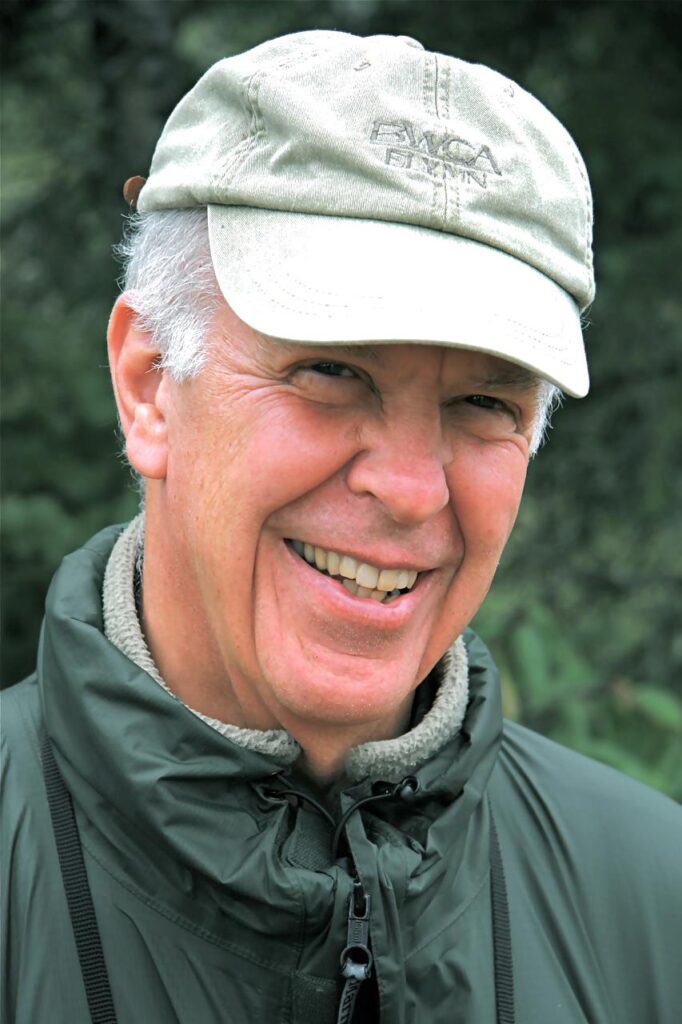

In our first segment, bestselling author Parker Palmer tells us how he gained a love of poetry and how it helped him during a mental health crisis. He’ll also help us find a way into the practice of reading poetry for ourselves.

For the second half of our episode, award-winning writer Leah Naomi Green gives us an intimate and experiential look into how her poetry connects with motherhood and the natural world.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

What poems speak to you? Let us know in the comments and also check out a list of some of Parker Palmer’s favorite authors in the credits tab.

Download the transcript and discussion questions.

Discussion questions

- Parker Palmer says that poetry can help us approach truths by looking at them from another perspective. Did any of the poems in this episode do that for you?

- Leah Naomi Green says, “I think there’s some spiritual courage in writing about spirituality at all.” In what ways can your work be spiritually courageous?

Jon Watts

Hello, dear listeners. It’s Jon here. Before we get started today, I just wanted to hop on and ask for your help. This podcast is listener supported, which means that we can’t do it without you. We have a goal of reaching 100 supporters by the end of June, and we’re currently around 70. If you’ve been listening regularly and have enjoyed what you’ve heard, and if you want to keep this project free and accessible to Quakers and seekers all over the world, I’d like to ask that you please consider becoming one of the 30 listeners that decides to support us and helps us meet our goal. Just go to QuakerPodcast.com and click on the button that says support. Thank you so much. Here’s the show.

Parker Palmer

Poetry has this amazing quality of kind of helping us look at things out of the side of our eyes out of the corner, right. The corner of the eye has more sensitive receptors. It strikes me that that’s exactly how poetry works. Look at it out of the corner of your eye. You’re likely to be able to absorb more of that truth and take it in even when it’s a challenging truth to your own life.

Various

Thee Quaker Podcast: Story, spirit, sound.

Georgia

I’m Georgia Sparling and I do not read poetry. Was I an English major? Yeah. Do I have poetry on my shelves and on my Goodreads to-be-read list? Yes and yes.

I do aspire to read poetry, and every April, which is National Poetry Month here in the US, I feel that pull anew, but it always feels kind of daunting — who do I read? What do I read? How much do I have to contemplate? Am I supposed to remember what iambic pentameter is?

Maybe you feel the same or maybe you love poetry, either way, this episode will have something for you .

So we’ve got two profound and thoughtful guests. First we have a wonderful conversation with Parker Palmer, the award-winning writer, speaker, and activist. Although he is now retired, Parker spent many years leading and developing long-term retreats through the Center for Courage & Renewal, and poetry has been an important part of those group sessions.

Parker is going to ease us into the practice of reading poetry by sharing his own story of how he came to love it, how it has been a way to engage with his mental health struggles, and how it connects with his Quaker faith. I found this conversation particularly helpful as a would-be reader of poetry.

And then for the second half, we’re really going to experience poetry up close by hearing from Quaker poet and literature professor Leah Naomi Green. She’s going to give us an intimate window into her writing process and shares some of her work. It’s going to be really special.

Ok. Slip on some headphones if you can and settle in. Here’s Parker Palmer.

Parker J. Palmer

My name is Parker Palmer. I live in Madison, Wisconsin. And I became a Friend through the Berea, Kentucky Friends Meeting back in the mid-90s.

Georgia

But before that Parker had basically surrounded himself with Quakers for a while. He and his wife and children spent 11 years at the Quaker retreat and learning center Pendle Hill, first as a student and then as the dean of studies. It was also where he began to see poetry in a new light.

Parker

Through college and graduate school, on those sort of rare occasions when I was exposed to poetry. It was a lot of, you know, bringing analytic tools to something that’s so profoundly intuitive and non-rational, not irrational, but non-rational.

Poetry calls on a different part of our brain and of our bodily apparatus for knowing.

At Pendle Hill, I had an opportunity to take a course from a really brilliant teacher of poetry named Eugenia Friedman. And as with most courses at Pendle Hill, she taught as we sat in a circle. And the teaching was not based on lectures, it was based on conversation, so that the question wasn’t, what did the poet mean by this or that? Which frankly was a question I didn’t care much about. But what does this poem mean to you? How does it intersect your life?

What questions does it raise? What images does it evoke? Eugenia Friedman created a dialogue between us and the poems, and it became as if the poem were the voice of another person in the room, the voice of a kind of archetype of human experience. That quickly engaged me because like all adult students at Pendle Hill, I went there with questions of meaning and purpose in my life.

Questions that are hard to kind of run at headlong with analytic tools and make any sense out of anything. But poetry has this amazing quality of kind of helping us look at things out of the side of our eyes, out of the corner of our eyes. Astronomers will say if you stand under a darkened sky at night and are gazing at the heavens and learn to look out of the corner of your eye, you’re going to see more of the dim distant stars than you will if you just stare headlong at that patch of sky because the corner of the eye has more sensitive receptors in it. It strikes me that that’s exactly how poetry works. Look at it out of the corner of your eye, you’re likely to be able to absorb more of that truth and take it in even when it’s a challenging truth to your own life.

Georgia

So tell me, how does poetry factor into your daily life?

Parker

So, I have a morning ritual of reading a new poem or two, which is often conditioned by, I guess by how I wake up feeling. I try to read poetry as sort of full body immersion, which is also to say full mind immersion, if the mind is distributed throughout the body.

Georgia

But Parker says his favorite way and perhaps the most transformative way to read poetry is within a group setting, which is something he’s facilitated many times throughout his life.

Parker

I find that putting a poem in the middle of a group, asking people to open it up from their various points of view and to listen carefully to what each other is saying and not to argue with each other about interpretations. I mean poetry in its very nature, I think, is ambiguous. I’ve always felt it was kind of like a Rorschach test that, you know, you see in it what you see in it.

And there’s no definitive way of saying, wait a minute, you’ve got that wrong. That, I think, is the most satisfactory way of reading poetry.

Georgia

So where is the connection between poetry and the spiritual life for you?

Parker

Since I learned about Quakerism at age 35 and eventually became a Quaker, it has seemed to me that the link is very, very close and really very intimate because in the unprogrammed tradition, Quaker tradition in which I was most deeply formed, we don’t worship the silence, we worship in the silence. So everything is rooted in silence. And if ever there were an indirect way of holding the great mysteries of life, silence has got to be it. The mystery that we sometimes too casually name as God or grace or light or whatever the language may be.

Sometimes the only response to the human experience of these things is silence. Not because we don’t want to talk about it, but because the language fails us. And so silence is very much like looking out of the corner of your eye at things that are too vast and mysterious to apprehend by running headlong at them. So at very least for me, there’s that connection with the kind of fundamentals of Quakerism.

But let me answer your question not only in terms of meeting for worship and some big Quaker themes. But I want to answer it more personally and if I may in the course of doing that also read a poem that I wrote.

So as I’ve written in a couple of my books, especially Let Your Life Speak, three times in my adult life I’ve descended into profound clinical depression.

And during that first immersion in a really devastating experience that went on for months, and I wasn’t altogether sure whether or how I could emerge from it. It wasn’t just feeling sad, it was a sort of annihilation of self.

Georgia

Parker went on a retreat to a religious center in Kentucky where he hoped to heal and while there, he went for a walk on a country road.

Parker

I looked to my right and I saw this recently plowed field. It was spring and nothing was growing yet, but the soil had been thoroughly tilled and stuff uprooted. In farming lingo, they called it harrowing, which I knew because of my Midwestern roots. And the word came to me with double meaning.

The field had been harrowed, and I was going through a harrowing experience. And this poem, one of the first poems I ever wrote, began coming to me. It’s called “Harrowing,” and I’ll read it right now.

Harrowing

The plow has savaged this sweet field

Misshapen clods of earth kicked up

Rocks and twisted roots exposed to view

Last year’s growth demolished by the blade.

I have plowed my life this way

Turned over a whole history

Looking for the roots of what went wrong

Until my face is ravaged, furrowed, scarred.

Enough. The job is done.

Whatever’s been uprooted, let it be

Seedbed for the growing that’s to come.

I plowed to unearth last year’s reasons—

The farmer plows to plant a greening season.

What’s hard to communicate is how that poem became a kind of container for my own healing. Because from my unconscious, and all the other faculties that I brought to that moment, came this image of how I had been plowing to uproot my life, but that’s just the first step in planting seeds that will grow in the future. So whatever’s been uprooted, let it be. Enough, the job is done.

I’ve written 10 books and hundreds of articles and lots of poems, and I sometimes feel like the most important word I ever wrote was that word “enough.” You know, that there was something in me that was saying, there’s a way forward here. And that poem gave me a vehicle to move forward with my own life. The writing of it was for me profoundly therapeutic.

Georgia

Although Parker is now retired, he still uses poetry as a way to bring people together for reflection. He now does that online through his robust Facebook page. There he often posts poems accompanied by his thoughts, ranging from politics to the death of a friend.

Parker

I like to put poetry on Facebook because poetry is elegant and Facebook isn’t.

My own thinking gets stimulated by reading a poem and finding it resonating with me because in addition to posting a poem, I’ll always post a commentary of some sort about how and why this poem speaks to me, how and why I think it might speak to some others. I feel good about the fact that that page, that Facebook author page, which now has about like 130,000 followers, is a place where there’s a larger conversation about meaning, purpose, and living well. Living well and dying well.

Georgia

One of Parker’s recent and very popular posts was about death and dying in light of a friend who had recently passed away. To accompany those thoughts, he shared a poem by one of his favorite authors, Mary Oliver, and I asked him to read this piece.

Parker

Okay, so again the poem is called When Death Comes and it’s by Mary Oliver.

When death comes

like the hungry bear in autumn;

when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse

to buy me, and snaps the purse shut;

when death comes

like the measle-pox;

when death comes

like an iceberg between the shoulder blades,

I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering:

what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness?

And therefore I look upon everything

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

and I look upon time as no more than an idea,

and I consider eternity as another possibility,

and I think of each life as a flower, as common

as a field daisy, and as singular,

and each name a comfortable music in the mouth,

tending, as all music does, toward silence,

and each body a lion of courage, and something

precious to the earth.

When it’s over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it’s over, I don’t want to wonder

if I have made of my life something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself sighing and frightened,

or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply having visited this world.

Having just recently turned 85 at an age in which, you know, mortality is much more on your mind than it was in previous decades. It strikes me more and more that I cannot imagine a sadder way to die than with a sense that I spent all of these years on earth and never really showed up as who I am. I think if we show up with our own truths, which I’ve always felt to be the kind of basic call of the Quaker tradition, then it seems to me we might be able to check out with a sense of satisfaction.

Georgia

That’s really great. Thank you so much.

Parker

I’m delighted. Thank you for asking me.

Georgia

And that feels like a really great bow on our conversation, so thank you.

As I listened back to my conversation with Parker, one thing that was particularly memorable for me was how the creative act of poetry was so important to him during a time of deep depression.

Parker has found a deep connection between both poet and poem and poem and reader, but it really requires the equivalent of stopping and looking to the right as he did while passing that field. I think our next guest is a perfect compliment to our conversation with Parker. Leah Naomi Green is all about stopping and listening and learning from her own poetry.

That’s after this break.

We often like to share stories of the people who listen to this podcast, so I recently called up one of our board members to learn why she signed on to be part of Thee Quaker Project.

Lisa Motz-Storey

Well, hi, Georgia. I’m Lisa Motz-Story, and I live just outside of Denver in the mountains and I attend Mountain View Friends Meeting.

Georgia

So Lisa, tell me a little bit about what drew you to Quakerism.

Lisa

Well, I actually started out as an ordained United Methodist minister, and I left the Methodist church over gay rights back in 91. And I had visited Mountain View Meeting and knew a little bit about Quakers. And I wanted to join a faith community that pulled me more in the direction that I wanted to go instead of me being inside of an organization. IThat I was always trying to drag toward change and the future. Quakerism has always challenged me, pulled me more in the direction that I know I need to go and continue to help me grow. And I’ve been a Quaker for most of my adult life now. Yeah.

Georgia

Lisa, you’ve known Jon for a little bit. When you heard about his plan to start a Quaker media organization what were your thoughts?

Lisa

A lot of people just don’t know the Quakers exist. And a lot of the people who are Quakers and are really active, or older, and we just, you know, we’re like, how can we get people to find Quakers? How can we get young people? And this is the way to do it. I was just really excited that by doing media like this, that you would reach an audience that had never heard of us, or maybe sort of heard of us and get the message out about what we believe and what we do.

Georgia

Yeah. Well, you’ve been listening to the podcast, tell me a little bit about how it’s impacted you so far.

Lisa

I was surprised that every single time I learn something new, or I’m challenged in some way, by somebody’s spiritual practice that they share. And I realized that you get in a rut when you’re in a monthly meeting, and you’re just into what your monthly meetings doing and your community there and I find that every single time I learned something from the podcast, I feel like I grow as a Quaker myself. I mean, here, I thought it was for other people to find us. And it’s actually teaching me stuff and challenging me to grow.

Georgia

What’s your message for anybody out there who’s listening, who maybe is considering becoming a monthly supporter of the podcast?

Lisa

I would say that Quakerism still has something to say to the world. And this is a way to support getting a message out that is different than what we hear in mainstream media. And that could encourage people to work for social justice, to work for change, to find a community in which they can be spiritually grounded in that social justice work. And the podcast is such a good way to get that word out, get get it to people who are just so frustrated, and they want to be doing something, but they don’t know what to do. And so I would encourage people to support this because I mean, the quality is amazing. The content is amazing. And I just think it’s so worth it.

Georgia

Wow. Thank you so much, Lisa. I really appreciate that. If like Lisa, you have learned from this podcast, been encouraged by it or inspired by it, we would be so thankful if you would consider partnering with us to help us become a sustainable, long-term project. If just 11 of you sign up in April to become monthly supporters, we’ll be well on our way toward meeting our goals. Please go to QuakerPodcast.com to find out how you can become one of those 11 and support this work. We really appreciate all of our listeners. Thank you so much.

Welcome back. For the second half of our episode, my guest is poet Leah Naomi Green. Leah is a member of Maury River Friends Meeting in Lexington, Virginia, and her Quaker influences began early. She attended a Friends school in Greensboro, North Carolina as a kid and spent many summers going to Quaker camps where she developed a deep bond with the outdoors, one that has filtered into most areas of her life these days.

It shows up in her work as an eco-poet, which we’ll talk about more in a few minutes, and it naturally shows up in her life. Leah and her husband live with her two young girls in an ecological community where they really live off the land. She’s also a professor of English and environmental studies at Washington and Lee University.

As such, it’s in the early hours of the day when she is able to sit down and spend time on her craft as a poet. I asked Leah to record an audio journal for us to bring us into that process, and it comes complete with lots of birdsong. We’ll hear those audio journals throughout this segment. Here’s Leah.

Leah Naomi Green

It’s 5:34 in the morning, I’ve just taken out my laptop from where I keep it in a cabinet. I live in a small cordwood house. So it lives in a cabinet. And I just cleared away some arts and crafts, letter writing materials that my kids were working on last night, cleared them off from the table so that I can have a place to sit and write this morning, it’s dark out. Everyone in the house is still asleep. So I’m talking very quietly, sound carries easily here. Normally I might start a fire in the woodstove but today’s warm, it’s getting towards April. I just slid open the glass door so you can hear the birds.

My computer’s on. I am pulling up a document that I’ve been working on for years. My second book which is nearing completion. My guess is there won’t be much exciting sound here for a while. I have an hour to write. Before my kids wake up, and the day begins. I’m hoping it’ll be quiet until then.

Georgia

Leah’s work is wrapped up in the natural world. As a kid she spent many weekends camping on 13 acres of land that her parents owned out in the country and she can remember the exact spot on that land where she first connected to the wonder of her surroundings.

Leah

You can’t explain the magic of, you know, what happens. The mind and the place that it awakens in, you know? And that’s to paraphrase Wendell Berry, but there’s something that happens there. And so for me, that awakening happened on those 13 acres, you know, specifically on a rock in a stream in the woods and then Quaker camp brought in the community aspect for me. And I still am so grateful for that. American wilderness has a lot of mythology around experiences of nature having to be individual, right? So, you know, Thoreau and Muir and all our like nature dudes did it alone. And I’m so grateful to Quakers and to Quaker camp for specifically the Baltimore Yearly Meeting camps for making my experiences of nature communal experiences that were shared and I felt like it wasn’t something I had to maintain as a separate identity.

We would hike up the mountain and then we would sit on top of the mountain in silence together as 12 year olds or, or 15 year olds. You know, Like it really stabilizes the experience to have others there.

Georgia

Writing came naturally to Leah from a young age, but she started with stories because she thought that’s what writers did, but eventually she realized poetry was more true to her nature.

Leah

Poems make sense for my mind in large part because there’s a lot of things I’m not good at, but one thing I am good at is focus. So there’s this, focus in poetry, right? That I can just, one can just be in the moment of the poem entirely, and it can just be one moment. And from that moment, you can reach forward and backward in time, but really you’re just in that one moment. It’s just this intimacy with the poem itself, with the page.

This morning I’m starting by work on actually a poem about silence. Well a poem about throwing a stone back into a river which is also about freeing it from noise back into silence. Right now it’s called “To Knock the Poem from the Poem,” but we’ll see what it ends up being called.

I’m an intense editor. Most of my work is editing so there’s the magic of the poem happening and then there’s like a year or two of me editing the poem and and that editing process that’s is where the learning happens for me like that’s the great that’s where i get to ask what I am learning from the poem right like um

Robert Frost says “it’s a trick poem that already knows its own ending,” and I think there’s some truth to that, right? Like, um, and sometimes I write a poem and it does know its ending, but even if it’s ended it still has so much more to teach me.

Georgia

Leah works on a few poems at a time, but never more than 10 a year, she says. Her poems are slowly shaped and refined and they’re meant to be savored, which is appropriate for a book called A More Extravagant Feast. The book came out in 2020 and won the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets.

Leah

So that book really came out of two pregnancies and two child births and experiences of nursing. And also all of that while living here in this ecological community where I live in rural Virginia. And those two factors combined towards this very real experience of realizing that my body really is a continuation of the land and that very real energy that makes my body work and move is the same energy that helped me to make another body and to nurse that body, right? And then to feed that body from the garden. And that experience of pregnancy and childbirth and nursing really took these ideas that had been given to me by Quakers and Jews and Buddhists and…

Um, and really honestly, largely Quakers, um, with my experiences through the Quaker camps and these experiences of like valuing nature, um, as, as a sort of social value. Uh, once I was pregnant, that stopped to, that ceased to be an abstract value and started to be so real to me. Like, and like all of a sudden, it ceased to be just an idea that I was part of nature. It became very real that in fact that there that without the garden there was no me. Without me there was no baby right? What is my body? What is her body? Became a real question and not an abstract spiritual question.

Georgia

I asked Leah to share one of the poems in her first collection that embodies that experience of pregnancy and motherhood. As she reads it, I encourage you to think back to our earlier conversation with Parker. What images does it evoke? What does it mean for you? If you can, listen a few times or come back to it later. Ok here’s Leah.

Leah

Let’s do “Arrival”

Arrival

When the moon cast a shadow for each tree, the same direction on the snow, it did not cross or entangle them. When you appeared in the lambent world, it was not on a long or wooded walk anywhere on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded walk anywhere, not on a long or wooded

or directly.

operating room, my troubled form gone gibbous. It was before that, when he and I rubbed two cells together because that was what we had. No, before that too, and never was there a moment when you were not already in the motion of materials of love, which we call atoms, because we must call it something turning to the sun, the seed that is the fruit.

already the seed begun.

into its middle. Your shadow casts itself now, discreet from mine on the snow.

made me human, which is to say,

which is to say that your face, the moon, is tilted up now

of your own volition, reflecting, producing light.

Georgia

I’m wondering, the act of writing poetry, of making time for poetry, for silence and for even just being outside in nature interacting — is there an aspect of spiritual courage for you in that?

Leah

I think there’s some spiritual courage in writing about spirituality at all. It’s not what most people are writing about these days. I would say that spiritual poetry is not what’s in right now. And so they’re, yeah, so it does take some courage just to be like, yeah, but this is what’s actually real for me.

Georgia

So I thought that one of your most overtly spiritual poems was “Narration Transubstantiation.” Would you read that for us?

Leah

Narration transubstantiation

And this one has an epigraph that reads, God is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere, their circumference nowhere.

One. The peony, which was not open this morning, has opened, falling over its edges like the circumference of God, still clasped at the center.

My two month old daughter’s hand in Palmer reflex, having endured from the apes, ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny, clutching for fur.

Her face is always tilted up when I carry her. Her eyes always blue. She is asking nothing of the sky, nothing of the pileated woodpeckers, their directionless wings, directed bodies, the unmoved moving. v

Two, hold still song of the woodthrush, smell of the creek and the locust flowers white as wafers on the branches. Communion, pistol, stamen, bee, hold still. She doesn’t say a word.

Three. When we eat, what we eat is the body of the world. Also when we do not eat. She is asking the sky for milk. Take and eat, we tell her. This is my body which is given for you who are here now, though you were not, though you will be old, then absent again. Sad to us thinking forward in time but not back. Not sad to you at all. The peony whose circumference is everywhere, you whose head now is weighted to my chest, the creek stringing its lights along next to us, the peony which has opened.

Georgia

In addition to a spiritual element in her poetry, Leah also joins the newer genre of eco-poetry. As I understand it, ecopoetry is less human centric than nature poetry and often includes element of justice and ethics. It also isn’t only focused on nature, but the connectedness of the world. For example, in the poem “The More Extravagant Feast,” Leah combines the experience of participating in their small town’s Christmas parade with her husband dressing a dear that he’s just killed on their land.

Leah

I really am much happier in this tradition of eco writing, which is a much newer tradition where we, where we acknowledge from the get-go that we’re part of a larger world, um, that humans are animals. And we’re one animal among many animals and plants and minerals in a larger world.

We’re not special, we’re not worse than, we’re just part of it and we have to figure out how to do that in a way that works, in a way that’s responsible. And I also, I love the tradition of eco-writing too because once you do that, there’s room for things like cities and there’s room for, community, other people, societies.

All of a sudden we realize there’s really one world that we’re drawing from and everything we eat and everything we wear and everywhere we live comes from that world. It’s not just a place for art or contemplation, but it’s actually the world we’re living in and using and contemplating and it’s feeding our spirit and our bodies that these things aren’t separable.

Georgia

I asked Leah to share another poem with us that I really loved and that felt particularly tied to this new tradition of eco-poetry. For this next poem, it might be helpful to note that a chaparral is a dense thicket of shrubs or dwarf trees.

Leah

Field Guide to the Chaparral.

The fire beetle only mates

when the chaparral is burning

and the water beetle

will only mate in the rain.

In the monastery kitchen, the nuns

don’t believe me

when I tell them how old I am,

that you were married before.

The woman you find attractive

does not believe me when I look at her kindly.

There are candescent people in the world.

It will only be love

that I love you with.

When we get home,

there will be our kitchen, the dishes undone.

There will be our bedroom.

What is it you eventually recognized in my face

that allowed you to believe me?

Beauty that did not come from you—

remember how it did not come from you?

As white sage does not come from the moon

but is found by it and lit.

The Buddhists say

that the front of the paper

cannot exist without the back.

Because there is a there,

there is a here. Chaparral,

the density of growth,

and the tattered chaps

the mappers wore through it

because they had to,

to keep walking without

being hurt. It is okay if we hurt

one another.

Chaparral needs fire

(the pinecones cannot open

otherwise). Love needs lover,

whose last lover was flood.

It’s getting light out now. I can smell the wood that my partner just finished cutting and stacking for next winter, which is great. It means we can start on the garden now that that’s done. Things are waking up, which means I’m done writing for today.

Georgia

Thank you for listening and thank you to Parker Palmer and Leah Naomi Green for sharing their thoughts on poetry in their own work. If you’d like to hear more from Parker Palmer, he has a podcast himself with our recent guests Carrie Newcomer is called The Growing Edge. We’ll include a link to that, a list of poets that Parker enjoys and more on our episode page.

While you’re there, you can also learn more about Leah Naomi Green who is currently working on her next book of poetry. There’s no publication date yet, but in the meantime, you can definitely check out The More Extravagant Feast, published by Grey Wolf Press. That’s at QuakerPodcast.com where, as a reminder, we also have a transcript for every episode of the show, as well as discussion questions and an opportunity to share your thoughts on the episode page.

Please tell us about your experiences with poetry and feel free to share a favorite poem or poet with us. This episode was written and recorded by me, Georgia Sparling. Jon Watts wrote and performed the music. Studio D mixed the episode and Your Moment of Quakers Zen was read by Grace Gonglewski. Thee Quaker Podcast is a part of Thee Quaker Project, a Quaker media organization whose focus is on lifting up voices of spiritual courage and giving Quakers a platform in 21st Century Media. If you want to partner with us, please consider becoming a monthly supporter. Every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way, and it makes this project more sustainable. Visit QuakerPodcast.com for more information, and now for Your Moment of Quakers Zen.

Grace Gonglewski

Dan Seger, 1983: To the extent that the blessing of peace is achieved by humankind, it will not be achieved because people have outraced each other in the building of armaments, nor because we have outdebated each other with words, nor because we have outmaneuvered each other in political action, but because more and more people in a silent place in their hearts are turned to those eternal truths upon which all right living is based. It is on the inner drama of this search that the unfoldment of the outer drama of history ultimately depends.

Georgia

Sign up for daily or weekly Quaker wisdom to accompany you on your spiritual path. Just go to DailyQuaker.com. That’s DailyQuaker.com.

Recorded, written, and edited by Georgia Sparling.

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Mixed and mastered by Studio D.

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

More from our guests:

- Parker Palmer is a writer, speaker and activist who focuses on issues in education, community, leadership, spirituality and social change. He is founder and Senior Partner Emeritus of the Center for Courage & Renewal, which offers long-term retreat programs for people in the serving professions, including teachers, physicians, non-profit leaders, and clergy.

He is the author of 10 books — including several award-winning titles — that have sold more than two million copies and been translated into 12 languages, including Healing the Heart of Democracy and Let Your Life Speak.

To hear more from Parker, listen to his podcast The Growing Edge with musician Carrie Newcomer.

A few of Parker’s favorite poets- C.P. Cavafy

- Billy Collins

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Langston Hughes

- William Stafford

- Mary Oliver

- Find more on his Facebook page.

- Leah Naomi Green is the author of The More Extravagant Feast (Graywolf Press, 2020), selected by Li-Young Lee for the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets. She is the recipient of a 2021 Treehouse Climate Action Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets, as well as the 2021 Lucille Clifton Legacy Award. Her chapbook, The Ones We Have, received the 2012 Flying Trout Chapbook prize. Her work has appeared in or is forthcoming from The Paris Review, Tin House, Poem-a-Day, The Virginia Quarterly Review, The Southern Review, Orion, Shenandoah, Ecotone, and Pleiades. She has been supported by fellowships and grants from Civitella Ranieri Foundation and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and is currently the Sherwood Anderson Distinguished Visiting Writer in Poetry at Guilford College. Green teaches Environmental Studies and English at Washington and Lee University. She lives in the mountains of Virginia where she and her family homestead and grow food.

Leah is teaching an online poetry writing workshop this summer. Registration ends soon. Learn more.

Hi Georgia,

I too am an English major who never took to poetry. This week’s episode inspires me to try again,…. and then again….to appreciate poetry.

If you find something you really love, let me know! I am finding that listening to poetry is the most accessible way for me right now.