How to Vote Like a Quaker

On the eve of a major U.S. presidential election, we’re exploring what it means to be a politically engaged Friend. We’ll hear from Diane Randall and Emily Provance, who will offer hope and guidance on how to engage faithfully. They’ll address voting, political violence, and engaging with people who have different opinions.

And if a Quaker government sounds good right about now, then you definitely need to hear our segment on the rise and fall of a Quaker-run colony!

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Leave a comment below to share your stories and thoughts!

Download the discussion questions and transcript.

Discussion Questions

- Jane Calvert says Quakers in Pennsylvania’s legislature “had to decide between being good Quakers or being good governors.” Do you agree? Does it have to be either/or?

- How have you “othered” people with different political views? What can you do to engage in a meaningful and healthy way with your whole community?

Georgia Sparling: Before we get started, I wanted to give you a quick update. A few of you reached out to check on Friends Montessori School in Asheville, North Carolina, who had an ad in last week’s episode, given the devastation from Hurricane Helene, we wanted to let you know that we did get word from co founder, Canaan Brackens before we aired last week’s episode, and he said that they’re doing okay, both their teachers and the school. It’s definitely a tough situation there, and the whole region has a long road to recovery, but I saw on their Instagram that they are asking everyone to hold them in the light. And you know that certainly goes for everybody who was affected by the hurricane. So we’ll include a link to Friends Montessori school if you want to reach out to them directly and see how you can support them in this time. So yeah, we just wanted to give you that update. Thanks so much for asking how they were doing. Okay onto the show.

Emily Provance: I am not saying that our experience of urgency and crisis is not real. I am saying that we need to not be swamped by it, that these big waves that may be coming at us require us to hold on to what we know can be our anchor. And for that, we go back to those Quakers practices that our people have been doing for centuries.

Various: Thee Quaker Podcast. Story, spirit, sound.

Georgia: Hi everyone, I’m Georgia Sparling and today’s episode is the first in a two-part series on Quakers and politics. With the presidential election taking up all the air in the room here in the US, it felt important to look at the American context.

Although we are approaching this episode from an American lens, I don’t think the questions we’re asking are only applicable to the States, but given the moment many of us are in there’s a lot to consider.

Like what can Friends do in this time and place to be faithful God? Can Friends enact change in this divisive, contentious, often ridiculous political atmosphere that we find ourselves in? And what can we learn from past missteps? In the second half of this episode, we have a really important and timely segment with Diane Randall and Emily Provance, two Friends who have been active in political engagement and election violence prevention, respectively. They offer really wise counsel on responding faithfully in this tense political environment and share practical ways that we can be peacemakers in our communities. If you’ve felt at any point that you don’t know what to do, then you really have to hear this segment, so make sure to listen all the way to the end.

First though, I wanted to consider what it might look like to have a Quaker government. Would that actually be a good idea? Would it work? To find out, we have to go back a few hundred years.

Jane Calvert: My name is Jane Calvert. I’m a historian of the colonial period in America and the early republic. My research for most of my career has focused on Quakers and Quaker political thought, specifically in Pennsylvania.

Georgia: I called Jane to learn how colonial Quakers shaped politics, a topic she’d become fascinated with in graduate school.

Jane: When I got to graduate school for political history and was looking at early America, Quakers were everywhere. And I just thought, my goodness, you know, they are so important and so interesting. So that’s really what started my interest in them sort of intellectually. And I was spending a lot of time in Pennsylvania and I started attending meeting there and eventually my husband and I got married under the care of Friends and with a Quaker ceremony, and it’s been very much a part of my life and an interest for my whole adult life.

Georgia: So any discussion of early Quakers and American politics has to include William Penn, a British Quaker who was a founded Pennsylvania in 1681. Quakers basically controlled the colony until America gained independence. But, even though William Penn is literally immortalized in the name of the state, he had a fraught relationship with his fellow Friends.

Jane: Immediately Quakers started challenging his power and agitating against him, and they were sort of known as being very, like, not peaceful and ungovernable and really kind of rowdy. Tthey basically resisted him so much until finally they ended up writing a new constitution that basically wrote Penn out of power and gave all the power to the popular legislature, which was all controlled by Quakers at that point.

Georgia: Before getting booted, Penn had drafted Pennsylvania’s constitution giving equal power to upper and lower houses of legislature and to him, the executive.

Jane: But then he kind of had second thoughts, maybe knowing that his people could be rowdy and ungovernable, and he at the last minute gave himself three times as much power as the popular legislature, and that did not go over well with Friends in Pennsylvania.

They agitated and eventually more or less nullified his power and they nullified the power of the upper house. And so it became the only major colony with a unicameral legislature which gave all the power to the people or at least to their Quaker representatives.

And then they more or less just had hegemony in the colony until they were ousted by the radicals in 1776. And they really established the only theocracy in the colonies. There was religious liberty, but there was not separation of church and state. The state was entirely controlled by Quakers.

Georgia: Even though Quakers had the upper hand politically, the situation was complicated.

Jane: Things got messy when the French and Indian War started.

Georgia: This was in the 1750s and ’60s.

Jane: Because they didn’t want the war, they did not want to fight and kill Native Americans and yet they had an obligation as the governors, the rulers of Pennsylvania to protect inhabitants on the frontier from Indian attacks.

And so when they refused to call up a militia and refused to defend the frontier, that made the frontier’s people understandably angry and they reacted by you know taking it out on Native Americans and slaughtering peaceful Indians who had embraced pacifist Christianity so it was really awful.

Georgia: The confrontation led some Quakers to resign from the legislature, but others whose conviction about the peace testimony had, perhaps, faded, remained in power and maintained government control.

Jane: Things got even more complicated during the resistance to Britain because at first they were in favor of resisting, but then they realized that it could easily get out of hand, so they kind of withdrew. And as things heated up and it was clear that there were going to be open hostilities between Americans and Great Britain, they retreated into neutrality, which was never a position that Quakers had taken. They had always stood for justice and rights of oppressed peoples. And so they retreated to this neutral position and just said we’re not gonna get involved and that really angered a lot of people and made sort of the radicals even more kind of set against them. And it prompted really severe persecution, more severe persecution than they had experienced since, know, Puritan Massachusetts or late 17th century in England.

Georgia: These rising conflicts again challenged the Quaker peace testimony.

Jane: That became a huge bone of contention where when we get to the French and Indian War there were a group of Quakers who were sort of more traditional who kind of separated their responsibility as governors or legislators and said, okay, well, “I am a pacifist, I won’t, whereas I will not fight in a war and I will not kill. I understand that because I am a legislator, like the government has certain duties to its constituents. And so we will give money for the king’s use,” quote unquote and whatever the king does with it, if the king wants to raise a militia, the king can do that and we’re not going to stand in the way. But then in the mid-century, at the French and Indian War, the peace testimony kind of transformed, so they no longer allowed money for the king’s use and they objected to taxes for war or any kind of waging of war. So in short, were relatively unified, relatively monolithic, but that doesn’t mean that Quakers agreed on everything all the time.

Georgia: I wondered about other spiritual convictions that had political implications — for example, did the Quaker belief in equality extend to women’s suffrage?

Jane: Women in New Jersey did vote. And New Jersey was also a Quaker colony and it had a very large Quaker presence and lots of Quaker leaders in the government. But that didn’t last. I mean, so Quakers sort of faded out of office there as well and women were gradually denied the vote in New Jersey but that was the only place that women were allowed to vote anywhere for any time.

Georgia: But back to the impending revolution against England.

Jane: The debate over independence really broke out into the public after Thomas Paine wrote “Common Sense” in January 1776. And so he came out and his purpose in writing “Common Sense” was particularly to basically nullify the Quakers’ power and get the Quakers’ enemies in Pennsylvania to rise up against them and remove them from power. And it worked. So right after Payne wrote “Common Sense,” the Quaker meeting wrote a response. And they basically said, like, you know, we are going to, you know, stay loyal to Britain, in fact, even to the king, and Americans really need to look at themselves and ask why this is you know, all this British oppression is coming upon them and it might be because they themselves are living sinfully, you know, they look, they own, they enslave people. And so like, look, we’ve brought this on ourselves. This is our punishment. And that just made pain and other people even angrier. So they came after them even harder.

Georgia: Thomas Paine’s letter galvanized the folks who were already angry about the lack of support during the French and Indian War. They pushed the Quakers out of power and took the colony through the Revolutionary War.

And although the coup had been peaceful, the aftermath was not. Quakers weren’t loyal to the crown, — those people were actually treated way worse — but Quakers’ refusal to show patriotism in the fight against Britain brought ire and persecution.

Jane: Thomas Paine and John Adams and some other radicals they basically made up a conspiracy that Quakers were assisting the British and they made up this meeting that they called Spanktown Meeting and they said that there were papers that they had found proving that Quakers were in cahoots with the British. And then under that pretense, Congress ordered the Pennsylvania government of radicals to arrest all the leading Quakers in Philadelphia. And so they did, they rounded them all up and without warrant and locked them in the Mason’s Lodge and held them, they then, and they refused to give them a writ of habeas corpus. They refused to, which of course is one of the rights that we were fighting for, one of the most basic rights of like, you know, due process. They were totally denied due process. And they were shipped off to exile in Virginia. And so some of them died, some of them got very sick, their livelihoods were destroyed.

Georgia: This was about 20 Quaker leaders. Meanwhile those who were still in Philadelphia were harassed in public and had their businesses threatened.

Jane: And of course, the American patriots were purporting to be fighting for liberty and all of the rights of Englishmen that they felt that Britain was denying them. And so then they just turn right around and do the same thing or do worse to people who are their neighbors.

Georgia: Philadelphia is still known as a hub of Quakerism, so obviously many Friends endured the ordeal and continued to live there.

Jane: They still felt like they had work to do. They were starting in more seriously with abolition at that point. so, of course, the federal government was in Philadelphia, so they would have easy access to Congress to petition and try without any success to recognition for abolition at the highest levels of government.

Georgia: What kind of can we learn from this period of history today? Like what can Quakers take away even as we are in a very heated, divisive climate?

Jane: My answer is that Quakers, they provide a really valuable lesson for all Americans about separation of church and state because they felt as powerfully about the peace testimony and all of their other testimonies, they felt as powerfully about that as evangelicals today feel about any of their issues and yet you know they recognized that they had to make a choice between being faithful to their to their their beliefs and to their understanding of God’s will. You know they had to decide between that between being good Quakers or being good governors. They realized that they couldn’t do both. And they also realized that it was not in their best interest as Quakers to be forcing other people who were not Quakers to act like Quakers and to try to compel people to live by principles that they didn’t necessarily share. And so it’s really kind of a noble thing. They gave us this really great model for how to engage with the world and also how not to engage with the world.

Georgia: Today’s sponsor is Arch Street Meeting House Preservation Trust in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a historic site and museum that is also home to the Monthly Meeting of Friends of Philadelphia. I spoke with executive director Sean Connolly to learn more about this iconic Quaker hub.

Sean Connolly: The building has always been used as a museum since 1904 when we installed our first exhibits, while at the same time also having the spiritual stewards of the building be the monthly meeting. A lot of our visitors come in, and this is their first experience in a Quakers space, or even knowing that Quakers still exist, we see around 50,000 or so visitors a year, 94 percent are non-Quakers. And so we have the great privilege to be able to share the amazing story of Quakerism with all these visitors.

Georgia: The public, especially Friends, are invited to be part of some exciting things happening at Arch Street.

Sean: And so we’re really excited to be able to celebrate 220 years of this building, sort of holding the mantle of Quakerism in Old City, Philadelphia. And so we’re planning a big celebration that will also overlap with friends select day here at Arch Street, which will be filled with fall activities to celebrate the meeting house’s construction. That is going to be october 27 everyone’s invited for meeting for worship, of course, and then we’ll have a potluck, and it should just be a really fun day filled with lots of fun, family friendly activities.

Georgia: Along with this momentous anniversary, the Preservation Trust is in the process of reimagining its exhibits so that they better explain the history of Quakerism and the importance of Arch Street. Those exhibits are scheduled to go live in spring 2025.

Sean: We’re telling a cohesive, full story of the history of Quakers in Pennsylvania and beyond, and that will have unique opportunities to tell the story of Black Quakerism, for instance, so we’re able to reimagine all the exhibits in that space tell a more diverse and true history of Quakerism.

Georgia: The building is also an active part of the community. In addition to a food pantry, there are more than 150 community events and rentals every year. Sean hopes that Quakers will see all the events happening there and get involved with Arch Street.

Sean: Stop on by and see how engaged the public is in learning about your faith. Come see the museum exhibits and engage with some visitors.

Georgia: The museum is open Thursday through Sunday, 10 to four. And in the summer, Wednesday through Sunday, 10 to four, and don’t forget to attend their all day 220th anniversary celebration on Sunday, October 27. Find out more at historicasmh.org where you can also sign up for their newsletter that’s historicasmh.org find the link in our show notes. Now back to the show.

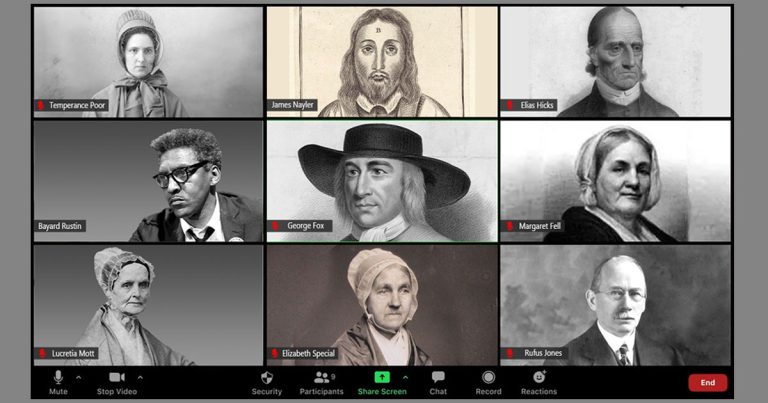

Last week we hosted our very first Thee Quaker Podcast event on Zoom and for our next segment, I’m bringing you a portion of that call. In case you missed it, it was called Help! There’s An Election Coming! And we talked about what Friends can do amid political tension, divisiveness and violence. As I put together this segment and relistened to the session a few times, I was really encouraged and definitely inspired by what both of our guests said and how they emphasized a spiritual response that felt very important and very practical.

So up first is Diane Randall, the former General Secretary of Friends National Committee on Legislation and also one of our board members at Thee Quaker Project. Diane worships with Friends Meeting, Washington in Washington, D.C. and she currently serves on the steering committee of the Urgent Call to the Religious Society of Friends. Here’s Diane:

Diane Randall: Yeah, unmute. Okay, here we go. I love the title of this event tonight, because I think it actually speaks to how a lot of people feel at this time, which is, help there’s an election coming, especially if you’re following news very closely. If you’re paying attention to social media, perhaps if you’re having some conversations with people who disagree with you, it’s not necessarily an easy time. People can feel very distraught over the divisions that we have. We have in our political system. What I think a lot about as a person who cares about public policy, who cares about politics and who cares a lot about spiritual health of myself, my community and and even of our country and our world? I think a lot about how these intersect in our lives. A little background about me. I was born and raised. Raised in the Midwest, I was very active in our Lutheran church growing up, politics wasn’t part of that. Wasn’t really part of our family life.

My parents voted, and when I grew up in the 60s and turned 18 in 1973 the ability to vote was a very big deal. And that was really how we saw for many people, that was what we thought as being great citizenship, was registering and going out and voting. And I would say that is great citizenship. And if there’s any message you take away from tonight is be sure that you vote this election. That said, I have come a long way in thinking about what citizenship really entails, and I believe it entails a great deal more than voting. And in fact, that is really what became my professional work. I taught high school for a while, and then I left that to work for doing work on the nuclear freeze campaign. And that really began a series of jobs throughout my life that were working for in advocacy and for peace and social justice. Just before I came to work at the Friends Committee on national legislation in 2011 I had been doing work on to address and homelessness and create permanent, supportive housing and affordable housing. I also, at one point ran and was elected to the local Board of Education in the town where I lived. So I feel like I have this view of how important elected office can be, and why it is so essential that we think of not only the presidential race, which has the attention of many of us, it has the attention of the country and the world of what might happen, but that we are aware that elections are happening in every state.

There are 11 governorships that are being contested now. There are 34 US Senate races. There are 435, races for House of Representatives. 44 states are electing state legislatures, and there are 145 statewide ballot measures in 41 different states. So there is a lot at stake here, in addition to the race for President of the United States.

As someone who’s done advocacy, I think it’s really valuable to get involved in races, because it allows a new way to start building relationships with elected officials. I would also say that the work that we do around elections should not end at the time after the election is over, and even after all the decisions have been made, because those elected officials need to hear from people. They need to hear from their constituents.

All that said, I’m increasingly feeling like there are some really broken parts of our democracy. I’m not alone in feeling that way, obviously, many people have wondered, what’s going on. Why has this country become so much more contentious, and why are we seeing sort of threats of authoritarianism, not only in our own country, but in countries around the world. And what does that mean? I think it means that we have some real work to do to really renovate this democracy. One organization that we’ve become somewhat involved in, and actually is led by a couple of people who are who are Friends, is Fair Vote, who has done a lot of work on ranked choice voting and opening up primaries. And in fact, some of those issues are on those statewide ballot initiatives that I’m that I mentioned states that are looking at creating ranked choice voting in their states.

There will be many opportunities going forward to think about what does the renovation of a democracy that truly promotes equality for everyone, and that is available to everyone, and that actually can rebuild the kind of trust that we should have in our electoral system and should have within our communities.

If you’ve been following the the Quaker Call, or we sometimes call it the Urgent Call. I’ll just say a little bit about that. We started the Urgent Call. All Out of a concern for the MAGA movement and what it was doing in terms of a sense of integrity and truth telling, and that it wasn’t that there was a lot of fear being spread because and a lot of lies being spread about the 2020 election.

I continue again, I’m going to be partisan here, but continue to be deeply appalled at the lies that are spread by the Trump campaign, and how that is harmful, not just to the people he is spreading lies about, which is absolutely dangerous, for example, if we think about Haitians in Springfield, Ohio, but also really a drag on kind of the the way that we even interact with each other, because people are so suspicious of one another. And I know that there are Republicans who feel the same way about Democrats.

I want to come back to this, the spiritual side of this, because it’s easy to get wrapped up in the political rhetoric and be exercised and angered by it, and so one of the practices that I really try to consider and use as as I am in this election season is to try to stay centered and try to be in worship with with my worshiping community, but also to take time during the course of a day, whether that’s through, you know, using the Daily Quaker devotionals that come out every morning, or through other means of being outdoors in nature and just grounding myself in a connection to God and staying centered. I come to this work because I believe we are called to the work of justice, and I believe we are called to the work of peace, and I believe it’s important that we do that with a sense of hope, recognizing that we’re human and we’re going to have fear and we’re going to find we’re going to be angry about things, but understanding that this work calls us to be fully present with the ways that we understand spirit to be moving in our lives.

I happen to believe that it is important for us to bring our spiritual selves into political work, because we know it matters who gets elected. It matters what policies they will put forward, and it matters what their character is. I will also just acknowledge that there’s no elected official who will do and be everything that I want that person to be. We will always be disappointed by the people who we elect because they’re not perfect and they will enact policies that we don’t necessarily agree with, which is why the continued advocacy after elections can also be so important is to continue to be in dialog about about this, and to continue to be in community

Georgia: I really loved a phrase Diane used about renovating American democracy. Those words have been replaying in my mind since last week’s session. I’ve been concerned about our democracy unraveling but I don’t think I ever gave myself permission to think of it being overhauled.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about what our second panelist had to say. Emily Provance is a Quaker traveling minister and an associate of Good News Associates, a Christian nonprofit ministry organization that supports individuals who are called to non-institutional ministries.

She speaks about a variety of topics of faith and practice, including leading worships on election violence prevention with a strong emphasis on peace and community.

Here’s Emily.

Emily Provance: I’m going to give you the five minute version of what I’ve learned about election violence so it’s going to be quick and not very deep. But then after that, I’m going to talk a little bit about what now like in the next month to six weeks. I’m giving you the five minute version of what I’ve learned, because it’s important, not just now, but in the years to come, and not just in the United States, but internationally. In fact, most of what we know about election violence prevention comes from East Africa, Central America and Asia, where people have been doing this work now for decades, and this is the reason why we have research that can point us in the right direction.

Election violence is notoriously unpredictable, I cannot tell you, and nor can anyone else exactly where, exactly when and exactly who. What we can say is that there are three significant social conditions that tend to exist before it happens. One is, does the country have a recent history of election violence. If it does, then the odds are better that it will happen again.

To give you a quick definition, election violence is physical violence or severe threats or intimidation or property damage that’s either motivated or intended to influence an election cycle. So it’s not limited to election day. That’s important to remember, a country that has a recent history of election violence, people might start to think that violence around elections is normal.

The best practices strategy that we have to interrupt that idea is peace, messaging, campaigns, people also might start to think that violence is necessary. The other side, quote, unquote, did it first? So we have to the best practice strategies that meet that are civic and voter education, giving as many alternatives as possible, and direct work with the security sector, with police and military forces making sure they have de escalation training and connections to the communities that they’re working with.

The second major social factor that tends to exist before election violence is if politicians are using blame based rhetoric, if they’re focusing on whose fault things are and who to blame, rather than focusing on talking about solutions. If politicians are using blame based rhetoric, people tend to get into a mindset of fear and anger and dehumanizing and otherizing, and that tends to lead to violence. The best practice strategies that we have to interrupt that are community forums and reaching out to make connections deliberately across the aisle. When I say connections, I’m not talking about ordinary people needing to have political conversations or make compromises. I’m talking about joining the bowling league or the softball team or the arts and crafts group at the local library so that we can speak to our neighbors about things like, what is your dog’s name and how are your children? That ability actually makes violence less likely. And the third and final factor that tends to make election violence more likely is if people are doubting the legitimacy of their government.

If people are doubting the legitimacy of their government, they may think that they have to engage in violence to get things done. And so the way we meet that is with very high quality Election Administration and Management, and that includes election reform that addresses the concerns of everyone, not one side or the other, but everybody’s concerns, so that everybody is able to rebuild trust in the election system.

That’s the basic content, it’s a lot of stuff, and there’s no way in the world that any one individual takes on all of those best practice strategies. But I do believe that all of us can find our place somewhere in that work. But if you’re thinking about the strategies that I just named, you’re probably also thinking about the fact that we have, like, I don’t know, 40 days before the election, 42 and you’re probably thinking, This doesn’t seem like a reasonable timetable, and you’re absolutely right. Election violence prevention efforts work best when they start at full force 18 months before election day.

So I’m giving to them to you, like I said, because they’re going to be as relevant, unfortunately, in the next election cycle as they are in this one. And so I want you to hold on to them. But I also want to talk briefly about what we do right now, this minute, today and tomorrow and next week. Here’s what I think it is.

I think we know that there are big waves coming. We can pray and hope that there won’t be, but I really think there are, and I don’t mean big waves only talking about violence. There may be additional violence, I don’t know. I. I’m also talking about very big, very serious feelings of fear and anger, and I’m talking about blame, and I’m talking about hearing a good and evil narrative in the news, and I’m talking about feeling a sense of urgency and crisis. I am not saying that our experience of urgency and crisis is not real. I am saying that we need to not be swamped by it, that these big waves that may be coming at us require us to hold on to what we know can be our anchor, and for that, we go back to those Quakers practices that our people have been doing for centuries.

I’m going to name just three of them. One is discernment. We know that when we have a sense of urgency, that when things start to happen very fast, that when there is a taste of crisis in the air. Sometimes we feel like we cannot take the time to slow down or stop and listen deeply to God, but we also know that if we try to act fast or by ourselves, without our communities, that we are likely to outrun our guide. The second practice I want to name is integrity. We know how important it is to be consistent and truthful and telling the whole truth and not part of the truth. This is how we become people that other people trust, because we never stop telling the truth. But there is a lot of pressure today to declare one’s loyalty and say this side of the political aisle is my side, and it is so important that we win, that I will say what needs to be said and not say what needs to not be said in order to make sure that that happens.

But the actual truth, as Diane said, is that none of our political leaders are perfect. The situation is almost always complex. And so when we are talking about politics and the conditions in the country, can we be truthful about all of the complexities? And the last one that I want to name is relationship. I think about all of our friends throughout history who have been witness types of people, and who have sat down at kitchen tables and said, I want to talk to you about this or that, because I am concerned about your soul. And when we do this, when we say, I have a concern for you. Friend, I want to be in relationship with you. Friend, I want to talk to you. I want to listen to you. I want to learn from you.

We are acting in a way that’s counter-cultural, because so often these days, the message we hear is if you engage with the quote, unquote, other side, then you are in solidarity with them. You are helping them. You are in some way, falling into impurity, and that’s not okay. But we know that change and transformation comes in the context of relationship, we know that we we have known that for so long, and so remembering that dedication to relationship and to integrity and to discernment, I think those are the pieces that we hold on to in the weeks that are coming up really fast.

The other thing that I’ve learned from reading about Quaker history and knowing our famous stories is that when we decide that we are not going to be on this side of the fight or that side of the fight, but we are going to be on God’s side, and we’re going to listen to the Holy Spirit, and we’re going to act as lead, something that very often happens is that both sides decide we’re on the wrong side, and we get caught and we get kicked from multiple directions. I’m not sure whether that’s a good thing, but it is a sign that we are walking in the steps of those who came before us, and it’s something that we know can happen if we insist on maintaining that sense of integrity and discernment and relationship.

So here’s the story I want to tell you, and it was actually a conversation in a hallway outside of an election violence prevention workshop. There was a man from Idaho, that I was talking with an evangelical friend, and he started asking me a series of questions about Jesus and the inner light, and I was answering him truthfully, and he just kept asking questions, and I could tell by the expression on his face that my answers displeased him, but I kept. Answering, and he kept asking. And finally, after five or 10 minutes of this, he took a long look at me, and he said, We don’t agree about almost anything, but if you’re ever in Idaho, come visit. And that is the spirit that I want us all to be able to carry with us as much as we can. Thank you, Friends.

Georgia: I really love Emily’s calls to action and I can attest to how helpful it is to be involved in a community with political views that are often different from my own and to join those communities without an agenda. It’s not always easy, but man does it help to humanize people.

And it’s as both Diane and Emily reminded me — the responsibility to be active in this work is not finished in november until the next election season. Just as we need to plan our voting strategy, so also it would behoove us to consider what we’re going to do next. There are always book clubs and pickleball leagues to joining, beach cleanups and litter pickups to volunteer for, letter-writing campaigns and voter registration drives.

You could also run for office…which is what next week’s guest did. And not just any office, the president of the United State of America. Tune back in next week to find out more.

Thank you to Jane Calvert for coming on the show. Jane’s new book Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson comes out this week from Oxford University Press. We’ll have a link in the show notes. Thank you also to Diane Randall and Emily Provance. I wasn’t able to include our entire Zoom event on this episode, including the Q&A portion, but you’re in luck, we’ve got a link to the whole event on our website at QuakerPodcast.com. We’ve also got resources that Diane and Emily shared with us.

And, if you’d like to hear even more from Diane and Emily, check out FCNL’s Oct. 30th event Friends’ Witness and Action for Our Democracy. From 6:30-7:30 ET. It’ll be a continuation of what they discussed on our Zoom event and also be very timely as it’s just days away from the election.

As always, check out our discussion questions and transcript at QuakerPodcast.com and leave us a comment while you’re there!

This episode was reported and produced by me, Georgia Sparling. Jon Watts wrote and performed the music. Studio D mixed the episode. Your moment of Quaker Zen will be read by Grace Gonglewski.

If you like what you hear, please consider becoming a Podcast supporter — you can do that on a monthly or a yearly basis. Head to QuakerPodcast.com and click on Support to learn more.

And now for your moment of Quaker Zen.

Grace Gonglewski: Sara Keeney, 2020: “Conflict can be an opportunity for growth, change, and improvement. However, our behavior during conflict is key. And our behavior is based on deeply ingrained experiences, drawn from cultural teachings and fears. Our responses may be more automatic than we realize.”

Recorded, written, and edited by Georgia Sparling.

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Mixed and mastered by Studio D.

This episode sponsored by:

Philadelphia’s Arch Street Meeting House (ASMH) has been the site of many important events in Quaker history, and we’re celebrating its 220th Anniversary on Sunday, Oct. 27th. All are invited to worship with the Monthly Meeting of Friends of Philadelphia and later enjoy family-friendly Fall activities like pumpkin carving, historic interpreters, and sweet treats. Whether you’re a local or from out of town, ASMH invites all to explore the museum and join our community of 52,000 annual visitors. We also welcome volunteers! Check our website for the latest hours and sign up for our newsletter at HistoricASMH.org.

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Images from Robert Green Hall, Harriet Smither, and Clarence Ousley, A History of The United States for the Grammar Grades and Freepik.com

Referenced in this episode:

- Watch our full Zoom session with Diane and Emily. Passcode: hF#m0$9*

- Penman of the Founding: A Biography of John Dickinson by Jane E. Calvert

- Friends Committee on National Legislation continues our conversation with Diane Randall and Emily Provance with Friends’ Witness and Action for Our Democracy, Oct. 30, 6:30-7:30 ET.

- Quaker Call to Action

- Friends Committee for National Legislation webpage

- FairVote

- Daily Quaker Message (an inspirational Quaker quote a day, sister project of Thee Quaker Podcast)

- Learn more about Emily Provance and her Election Violence Prevention workshops

- Update: Friends Montessori School in Asheville, North Carolina, is a Quaker school that was affected by Hurricane Helene. Anyone with a concern for this school is encouraged to reach out to them directly.

Thanks Friend. I love politics…. well, democratic politics!

I am reminded always of Ralph Blum’s classic line: “When something within us is disowned, that which is disowned wreaks havoc.”

I see Jesus as a proto-citizen (living under Pax Romana in a very narrow-minded religious community). As Quakers, we know he’s not coming a 2nd time (he’s here with us now!) And… if he did somehow miraculously appear, then sure, we’d give him the vote, and allow him to stand on whatever soapbox to sway people with his vocalised wishes. But even if he were elected, I’d still want there to be an official and encouraged Opposition (it tempers demagoguery).

I am moved to declare my most heartfelt wish here, as outlined in Matthew 18:18-19 —

18 “Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.

19 “Again, truly I tell you that if two of you on earth agree about anything they ask for, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven.”

My most heartfelt wish is not that we can agree on everything (that seems illogical to me, given that reason alone can give us valid and yet opposing answers to so many important and moral and ethical questions!)

My most heartfelt wish is that We The People (in whatever nation, between whatever nations) can agree to disagree agreeably and peacefully.

Is there anyone here reading this who can agree with me? In the name of Jesus Christ?

Democratic processes of free, fair and frequent secret ballot seem to me the best way of discernment as to who gets to police and judge with legitimacy the consequences of actions. What we prescribe and what we proscribe may be totally overturned by the next generation. We’ve seen that with slavery, women’s suffrage, same-sex relationships, to name just a few. The USA went to war over slavery. I pray we need never have violent conflict again, over any issue. Ever.