Weird Quaker Names Go Viral on Twitter

Isabella Rosner never imagined that her list of strange Quaker names would be liked, shared, and retweeted millions of times.

We asked Isabella where she found these unusual names (i.e. Experience Cuppage), and how deep dive into women’s needlework revealed not only Quirky Quaker monikers but also a colorful and lesser known side of Quakerism.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Check out these examples of Quaker needlework and shell and waxwork.

What did you think of this episode? Let us know in the comments below.

Download the transcript and discussion questions.

Discussion Questions

- “These people were building a world that was so materially rich that we almost can’t comprehend that,” says Isabella Rosner. Why is it significant that Quaker women of the 17th and 18th centuries created colorful artwork even as they wore plain dress?

- Isabella’s list of unusual Quaker names has been shared more than 6 million times on social media. What do you think about the interest that this post generated?

Jon Watts

Jane Quitquit

Georgia Sparling

Experience Cuppage, that’s my favorite.

Jon Watts

Love Beer

Georgia Sparling

Love Butcher

Jon Watts

Patience Fish

Georgia Sparling

Dolphin Munn

Jon Watts

Return Towle

Georgia Sparling

Wilde Wilde

Jon Watts

Oh, that’s a good one. That’s the first name and the last name?

Georgia Sparling

The name was so nice, they named him that twice.

Jon Watts

Okay, here’s a good one. Peace Love.

Georgia Sparling

No relation to Questlove Love.

Jon Watts

Not as far as we know. Olde Craven.

Georgia Sparling

Oh, he sounds like a fun guy. How about Jane Snowball?

Jon Watts

That’s a good one. Hester Chester.

Georgia Sparling

I’ll take your Hester Chester and raise you a Grissel Toldervy.

Jon Watts

I love that one. Okay, let’s see. Here’s a good one. Hallelujah Fisher.

Georgia Sparling

Job BLand

Jon Watts

Digworthy Marshall.

Georgia Sparling

Oh Elizabeth Poope. That one’s unfortunate.

Okay, so these are Quaker names.

Jon Watts

Very old, very odd Quaker names.

Georgia Sparling

Very odd. And they come from a list of about 90 Quaker names from the 17th and 18th centuries that went viral on Twitter back in May, back when Twitter was still called Twitter. And for the time being, we’re still just gonna keep calling it Twitter.

Jon Watts

Yeah. Good. Good plan. Yeah, so this list really made the rounds on Quaker social media.

Georgia Sparling

And non Quaker, I actually had quite a few non Quaker friends who DMed this list to me. And you sent it to me as well. So I’m curious, like, what was your first impression when you saw the list?

Jon Watts

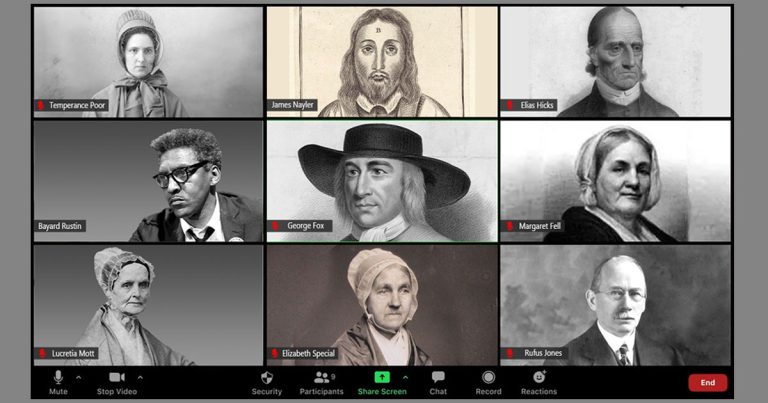

Well, I mean, so it’s hilarious. But it’s also telling, I mean, many of these names came out of a time when Quakers identified first and foremost as Quakers. And everyone around us knew it immediately, just by looking at us because of our style of dress, our style of speech, and apparently, our names. So there’s something interesting there about it to me how my spiritual ancestors, these Quakers of old didn’t hesitate to name their kids like Silence Williams or Temperance Poor, for example.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, they’re definitely very illustrative names. Yeah, they they stand out. So this list was collected and posted by an art historian named Isabella Rosner, and she specializes in early modern women’s needlework. She actually wrote her thesis on Quaker women’s artwork of the 17th and 18th centuries. So today’s episode starts with weird Quaker names of old but then we’re going to explore how Isabella’s research raises some interesting questions about women about our understanding of yield Quakerism and more.

Jon Watts

Great, let’s hear it.

Various

Thee Quaker Podcast: story, spirit sound.

Isabella Rosner

Okay, well, I’m currently sat on the floor. So it’s going to be certainly a vibe.

Georgia Sparling

That is Isabella Rosner.

Isabella Rosner

Who am I? I am a recent PhD. I can’t say graduate because I haven’t graduated yet. But I’ve just completed my viva or my defense for my PhD, which is all about Quakers.

Georgia Sparling

Isabella is from Los Angeles. But she spent the last few years in England working on her PhD.

Isabella Rosner

My accent has not changed, unfortunately.

Georgia Sparling

She’s also the curator of the Royal School of Needlework in England, and a research consultant for Whitney Antiques.

Isabella Rosner

Which is the Britain’s leading antique dealership of historic needlework. And it also is the largest stock of antique needlework in the world.

Georgia Sparling

Probably she has a podcast called “Sew What”? That’s a pun s-e-w. And Isabella has quite a following on social media. She’s got more than 11,000 followers on Twitter, nearly 20,000 on Instagram and she’s big on Tiktok, I just don’t have Tiktok. So I can’t tell you how many followers she has on there.

Isabella Rosner

I’m very surprised, kind of embarrassed by it. I think part of my success comes from the fact that I just post all the time. I did not expect any of my research or my interests to strike a chord with people. And I mostly started all of my various social media accounts because I saw a real gap. I saw a lot of content about other kinds of history or other kinds of art history, but nothing about embroidery.

Georgia Sparling

An advisor told Isabella that Twitter was a good place to make academic connections.

Isabella Rosner

I started tweeting a lot very aggressively during COVID because I had started my PhD in a new country in September of 2019 and then COVID hit, and I was like, Oh, I have maybe two PhD Friends, I haven’t yet built a community for myself, I guess I will seek that community online. And I ended up having a lot of success and meeting a lot of wonderful people that way.

Georgia Sparling

Including lots of people who weren’t familiar with historical embroidery.

Isabella Rosner

It was a real opportunity to stake my claim and to show people how fascinating how radical how beautiful historic stitch can be, especially because it’s a visual medium.

Georgia Sparling

We’re going to talk more about Quaker women and their artwork. But first, we must get to that viral tweet.

Isabella Rosner

Okay, so I should first off say that the timing of it was unbelievably bad, like, laughably terrible. I was submitting my thesis on the 17th of May. And on the 16th of May, in the evening, my brain was I was tired, my brain was mush. I sat on my couch and took a little brain break, and was like, You know what, like, I have collected so many weird names over the course of this process. I should just like, I’ll just make a little document and show them all at once. Because I had been tweeting about the weird names I was seeing, you know, every so often, every time I came across some weird names, I would tweet about it. And that had been going on for like three and a half years. And I was like, let’s just collect them. I think people would be interested in seeing it not like 6.3 million people. It’s actually 6.4 million now. I was thinking more like 100 people would think it’s fun. Um, and I made this tweet. And I noticed within the first minute, it had six retweets, and I was like, oh, no, it’s this. This is gonna get weird.

Georgia Sparling

This list of unusual and quirky Quaker names. It had gone viral.

Isabella Rosner

And then I got all of these texts from friends saying like, Experience Cuppage is trending. Love Beer is trending. You know, all of these names from the Quaker tweet, they were trending on Twitter, I found that so funny. But basically, I came to these names. Simply by looking at the Quaker records.

Georgia Sparling

These names were recorded on birth records, marriage records, death records, and meeting minutes. And there are about 90 names on the list. But let me just just be clear, it’s not representative of some huge trend in Quakerism, to give your children unusual names.

Isabella Rosner

Many of them are boring. Many of them are John Smith, and you know, Elizabeth Hudson, and pretty basic names. But every so often, I would just come across a name that charmed me, either because it was a sentence in itself returned towel, that’s a phrase, or because it was a name I’d never seen before Jennix Dry.

Georgia Sparling

The tweets popularity was surprising, of course. But it also gave Isabella a moment of panic, which may or may not have had something to do with the proximity to our thesis deadline. But, you know, that’s just pure speculation.

Isabella Rosner

I all of a sudden was like, Oh, my God, did I just make all these names up like they are. Some of them were getting so popular, and people were questioning them. And all of a sudden, I was like, Oh, my God, what if I just made these up, I gaslit myself into thinking I made them up. And I had to go back and find experience coverage. And yes, she exists. She married into the strettle family of Philadelphia. So she became experienced struggle, but it was joyous and reaffirming to kind of go back to these to these names that I hadn’t seen for a while some of them I hadn’t seen since you know, December of 2019, or whatever. And it was kind of like meeting old friends.

Georgia Sparling

Many people reached out to Isabella about the names.

Isabella Rosner

I think the Quakers came in first. They were they they scooted in there into the comments first, and they were very, they were really interested and and kind of loving it. I think some some of them expressed. Confusion is not the right word, but a little bit of shock. Because it does not align with perhaps it does not align with everybody’s interpretation of historical Quakers as all of my work, I think really does not meld easily with what people Quakers and non Quakers think about Quakers of the past. But for the most part, Quakers were loving it, and I was extremely grateful that they were.

Georgia Sparling

Isabella says there does seem to be a trend and Quaker naming conventions that may account for some of these odd ones.

Isabella Rosner

I do know that they had a tendency to name children, a former family name or a maiden name. So Parnell Mackett who’s one of my favorite Quaker girls that I study. She has an embroidered wax box that survives in a sampler. That name Parnell, bit of a weird one for a Quaker girl. But Parnell is a former family surname, and that’s how she got it as her first name. I think it’s probably the same with people like Jennix Dry, hard to tell. But that’s the only not even unique, but kind of yeah, I guess slightly different naming convention I’ve come across for Quakers.

Georgia Sparling

Why do you think people were so enamored with this list that it caught on so well?

Isabella Rosner

I think it was probably a few reasons one of them is that I think we all have an idea of Quakerism. That’s not very accurate and that is colored by the Quaker oatmeal, man. I don’t want to put that on everybody. But at least for me, I was like, Quaker oatman is an accurate representation of Quakers. Yeah, I was kind of the school of thought where I was like, ah, Quakers, kind of Amish adjacent, because I had no idea especially coming from L.A., where there is really no Quaker presence, I didn’t know. So I think that people really loved rewriting their idea of Quakerism. But I think more so people love learning that people of the past were as kooky as we are now. I think I see that with needlework all the time. People think that the past is a totally different place with different motivations and different behaviors. And that certainly is the case sometimes. But we’ve always wanted to be surrounded by bright things and to draw funky little guys. And you know, we draw rainbows the same way and hearts and stick figures and all that stuff. And I think people loved seeing that. Somebody’s naming their kid Apple is not a 20th or 21st century thing. It’s been going on for all of human history.

Georgia Sparling

Sorry, Gwyneth.

Isabella Rosner

Yeah. Sorry, when it’s like, great name, legendary, obviously. But Dare I say the Quakers maybe did it first. Not first, but the Quakers certainly did it before you.

Georgia Sparling

We’re going to take a short break, and then we’ll find out how Isabella even started studying Quakers.

Erin Bates

Hey, Jon,

Jon Watts

Hey, Erin, how are you?

Erin Bates

I’m good. How are you today? Can you hear me? Yes.

Jon Watts

All right. Thanks for taking a second to talk with me.

Erin Bates

Yeah, for sure.

Jon Watts

So you mentioned that you were relatively new to Quakerism and that my work had played some role in that. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about that story.

Erin Bates

Yeah, absolutely. So I first went to a Quaker meeting in November of 2021. And before that, I was part of a very, very conservative, fundamental evangelical Christian church, and my partner was not. And we were trying to figure out how to mesh our beliefs together. And he asked me to go to a Quaker meeting with him. So I opened my heart a little bit to the thoughts of Quakerism. But I didn’t know if I felt comfortable going to an actual meeting with people.

So I started looking on the internet about, you know, what is Quakerism. And very quickly, I found Quaker Speak. So, I remember very specifically, the first one that I watched was “Are Quakers Christian?” And there was an interview that said, in Quakerism, there are no lay people because we’re, we all have God in us. And I thought that was a really beautiful sentiment. This really started kind of opening my eyes to that the Quakers each had their own faith, and that that was okay. And that the group as a whole was not purposed to change my faith or tell me what to believe, but that rather, it was a guide to help learn how to live in this. I think the video might have even called it a “dynamic spiritual presence,” where we’re focused on community, and we’re focused on helping people in the world right now. That’s what convinced me to go to a meeting.

And so I went to my first meeting at Mountain View Friends Meeting with my partner. We heard some of the, I think it was the Peace and Social Justice Committee, they stood up and they said there was a recent shooting at a Jewish synagogue. And that Mountain View was looking for people to volunteer to go stand outside of a Jewish synagogue on one of their upcoming Holy Days, because they needed a peaceful nonviolent presence, so that the Jewish people could go and worship and peace, and that just sealed the deal.

Jon Watts

Thank you so much, Erin. I appreciate you doing this spontaneously.

Erin Bates

My pleasure, Jon. Have a good rest of your day,

Jon Watts

Okay, you too.

Jon Watts

If you’d like to support our work, we want to keep having rich conversations, like the ones that Erin discovered online that led her to Mountain View Meeting. This weekly Quaker podcast that you’re listening to right now is listener supported. So you can make a big difference by going to Theequaker.org and pledging a monthly donation to our Patreon. Thanks so much for your consideration. And now back to Georgia.

Georgia Sparling

Welcome back to the show, and to my conversation with Isabella Rosner. As we heard in part one, Isabella is an art historian. And it was through her research into Quaker women’s artwork that she encountered all of those amusing Quaker names. But I wanted to know why she was even studying Quaker women’s needlework to begin with, it seemed very specific,

Isabella Rosner

I have always been really interested in stories in the stories of women and people of color. And people who are oftentimes absent from the historical record women’s world has for a very, very long time been poo pooed. Because it’s, you know, women as the sort of lesser sex, that whole thing. And it’s this conflation of women’s work as craft versus art. So needlework is typically considered a craft. And for a long time, there was a hierarchy of art and craft, where art sat above that. And art would be things like paintings and sculpture, and architecture. And you know, these sorts of, I don’t know, art forms that are usually practiced by white men who are considered geniuses. And I say that in heavy quotation marks, but it’s this thing of the cult of the genius. Craft would be things like textiles, ceramics, metals, the things that you would have in more in the home and in the normal person’s home. That hierarchy is very messy, and it’s incomplete. It’s unfair, it excludes a lot of people. And I find it an incredibly unhelpful structure by which we can understand art. It has done a lot to minimize the work of women of people of color of people who are poor of people who are in guilds, you know, all these sorts of groups that don’t fall easily into the category of single, artistic geniuses.

Georgia Sparling

This interest started when an English teacher encouraged her to read classic literature. From there, Isabella watched the TV and movie adaptations and was enthralled with the costumes. She studied art history at Columbia, but found that she was learning more about white male painters than the artists and artisans that she was really interested in.

Isabella Rosner

So I found myself interning at a variety of museums. It started with the Nantucket Historical Association. It was the Metropolitan Museum of Art, LACMA, the Fitzwilliam, I’ve been very lucky to intern at a lot of places. And it was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that I started getting my first opportunities to study embroidery.

Georgia Sparling

The previous year, she had been introduced to this thing called samplers. We’ll have a link to some examples on our episode page.

Isabella Rosner

A sampler is basically a stitched exercise for a school girl, they were made for centuries, and it was a means by which a girl could practice her embroidery skills. I was taught about samplers and that opened up this whole other world to me, this world of girls and women and these individuals who are so often, totally not the people we find in history books. So when I started interning at the Met, I had the opportunity to research and installation about samplers, and it kind of went from there. I didn’t realize that there was such a rich, material culture of women and girls and that that material culture that their existence, their their work, the work of their hands existed in textiles, I had just never come across that before. So realizing that that’s that embroidery specifically offered an opportunity to study centuries of girls and women. I thought, That’s it. I gotta, I gotta go in that direction.

Georgia Sparling

Isabella went on to work at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia. And then she was introduced to another form of artwork by women, these sort of wooden shadow boxes with intricate scenes made of wax and shell.

Isabella Rosner

And I was like, these are crazy. They are amazing and they are beautiful. I don’t really understand what looking at, I went to the catalog to see more about them. And it turns out both of them were made by Quakers with very secure provenances.

Georgia Sparling

That’s the documentation of an object’s origin. And it’s used to determine authenticity.

Isabella Rosner

These were actually made by Quaker women in 18th century Philadelphia. And I found that very odd because it really did not align with my understanding of Quakerism and Quaker art. So up until then, I had had quite a few museum experiences, and I had worked with a lot of Quaker needlework from around 1800 onwards, and Quaker needlework is, is quite well known within the stitching world and a bit beyond it as being really stylistically singular, totally unique. It has these sorts of standalone motifs that are framed, and these samplers are usually in only one color, and they’re very, they’re very unique. And these boxes did not match what I had thought Quaker art would be.

Georgia Sparling

Isabella did some research, of course, and she found a chapter by Carol Humphrey of the Fitzwilliam Museum on 17th century Quaker samplers that were made in London. She realized something had definitely changed between the 17th century Quaker work and the more muted work of the 1800s and beyond.

Isabella Rosner

And the samplers were incredibly bright, very, very decorative, and just totally covered in stitches.

Georgia Sparling

Much like Experience Cuppage, this didn’t match her idea of Quakerism.

Isabella Rosner

Quakerism, from what I had been led to believe, and what I was finding in the records, was a religious organization that very much prided itself on being planed in speech in dress and behavior, in, you know, having a separation from the people of the world. And that is not at all what I was seeing in objects. There are many, many surviving 17th and 18th century Quaker needlework pieces. There is this wax and shellwork stuff. And there’s a few other types of objects, all of which is very bright, decorative, opulent, all of this stuff. And I found that divide, extremely frustrating, and there were no answers in the archive.

Georgia Sparling

Isabella wanted to know why these colorful and intricate pieces were acceptable within Quaker circles, and why that might have changed. So she did her research, combing through minutes from 100 years worth of Quaker meetings, as well as diaries, letters and publications.

Isabella Rosner

There are like almost no references anywhere, no references to wax and shell work. No references to women’s art or craft more generally, there is this, this vagueness and certain Quaker scholars correctly point to this sort of ambiguity of certain parts of Quaker behavior versus a lot of a lot of discipline about other parts of Quaker behavior. So dress, lots of notes about that stuff. You know, don’t wear your green aprons, don’t wear your white aprons. Don’t have your hoods too long, don’t have your collars too long, too wide. You don’t know lace, all of this stuff, lots of rules everywhere. Totally not the case with actual stitching or other types of Quaker women’s art more generally. So the answer is, I don’t know why this was happening. But she has some ideas, by theories are as follows. One is that these objects were useful that they were training for girls, in the early times of Quakerism. Especially in London, and in Philadelphia, many, many Quakers were merchants, and many of them very early on, were involved in the textile trades. So I often interpret this stuff as being part of a Quaker girl’s sort of formal education in her family’s business.

Georgia Sparling

It seems likely that adult women didn’t have time to devote to these detailed and ornamental pieces. Also, the needlework has motifs that reoccur across different schools and communities. The samplers often feature the same verses, including some that are only found on Quaker pieces.

Isabella Rosner

In particular, a few verses and the most common one is this verse that says, “Love thou the Lord and He will be a tender Father unto thee.” And that appears all over Quaker samplers, and it eventually gets to non Quakers as well. I have no idea where that verse comes from. I’ve not seen it in any written sources.

Georgia Sparling

There are verses or quotes, not necessarily from the Bible, but about God time children, some of them are from Puritans and other nonconformists. So there’s definitely an element of faith and belief exhibited in this work. But again, it’s kind of weird that they’re so elaborate, right? These are the endow speaking plain dressing Quakers.

Isabella Rosner

This work helps us change our understanding of Quaker women because I think for so many people, they view Quakers of the past as being isolated and up apart from the wider world, that is not at all the case here, these women and admittedly, this is a very specific and privileged group of women, these are women who are of the middling sort or of the elite, they have resources and time. But for these women, being a good woman, and I say that in heavy quotation marks, you know, being a pious, diligent, artistic, tasteful woman of the 17th and 18th centuries, was just as important as attending your Quaker meetings, and having a personal relationship with God and not dancing or not gambling, that sort of thing. Those identities are are not separate, and they actually come together to create these women. I also think that something that is forgotten about or maybe just not even known is that Quaker women of the past Quakers of the past were absolutely surrounded by incredibly decorative and brightly colored objects.

Georgia Sparling

It’s hard to know whether there were more quote, unquote, practical applications of embroidery and needlework.

Isabella Rosner

I don’t know if they were embroidering their clothes, it’s really hard to say because none of that survives. I do know that they were producing by the 18th century baby linens. And they were cutting out certain parts of the linen and doing a sort of lacemaking called holy point. And they were creating practical ish things like some things were practical pin balls were practical needle cases practical. Some things were not practical, like my favorite example, which is an embroiderer nutmeg, you would take this nutmeg extremely valuable, like, this is my favorite fact. And I tell everybody nutmegs at the time were worth more than their weight in gold, there was a 68,000% markup from when they were gathered in Indonesia’s Banda Islands to when they were sold in London, like so valuable, really important for food and for medicine. And this one Quaker girl just rendered four of these nutmegs completely useless by covering them in in embroidery, the the thing that’s hard about studying needlework generally is that the decorative stuff survives more often than the practical stuff, because the practical stuff was used and used until it fell apart.

Georgia Sparling

Although the written record of this needlework and waxwork is slim to none, their existence points to a few salient facts.

Isabella Rosner

It’s women teaching women, it’s women learning from other women, it’s women borrowing from women all around the world, and teaching daughters and granddaughters and that sort of thing. I think that there was a network of women’s work of women’s art that was happening, that those in power in various positions of Quaker leadership either knew about and didn’t care that that was happening, or they were blind to it. If you go to a home, you’re probably going to see their huge wax and shellbrook diorama it’s pretty hard to avoid, it’s gigantic, and it would be in a public place.

Georgia Sparling

So either it didn’t bother Quaker leaders that these pieces existed, or it never bother them enough to write about it.

Isabella Rosner

It’s very frustrating that contrast between what survives in in words and in objects. But it’s also nice in that the absence is tell us a lot. And it makes it really clear that even though historians and genealogists and people who rely very much on written records. It shows that written records are not everything. We know that there are gaps in those records, we know that they are oftentimes very exclusive, and they totally write out many people have many different experiences.

Georgia Sparling

Ultimately, the work of these young women shows us a more nuanced picture of Quaker women than we might have considered that their faith was wrapped up in these beautiful, colorful objects, that they had these creative and artistic outlets and communities that their homes are decorated with these beautiful and bright pieces. And that this was all a valued part of their growing up.

Isabella Rosner

You know, in 19th century photographs they’re wearing their big shawls and their bonnets and they look like Lucretia Mott. They look you know, they’re wearing brown and, and black and gray. That is not what’s happening here. They are using incredibly bright colors they’re using they’re using gold thread. They are using flakes of mica, that when you crush them turn into glitter. These people were building a world that was so materially rich that we almost can’t comprehend that.

Georgia Sparling

It’s really interesting to think about the inner world and just kind of the unknown experience of these early Quaker women. So thank you so much, Isabella, for such a fun and insightful interview and thank you to you for listening. You can check out our episode page to find images Have some of the Quaker needlework that Isabella mentioned. And, of course, a link to Isabella’s viral tweet and all the places that you can find her online. That’s at QuakerPodcast.com.

While you’re there, tell us in the comments what your favorite name is from Isabella’s list, you can also check out the transcript and ponder some of our discussion questions. Thee Quaker Podcast is part of Thee Quaker Project, a Quaker media organization with a focus on lifting up voices of spiritual courage, and giving Quakers a platform in 21st Century media. If you want to give to our work, we would so appreciate it, please consider becoming a monthly supporter, you can learn more about how to join our giving team at TheeQuaker.org. That’s TheeQuaker.org. Every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way. In case you haven’t seen it on social media, we are looking for a social media and newsletter coordinator as we expand our team, which is very exciting. There’s a link to the job description in our show notes. So please do check that out and forward it to your friends.

And remember, we would love to hear from you. There’s lots of ways to do that. Whether it’s a comment on Apple podcasts a comment on our website, or you can leave us a voicemail and share your thoughts about an episode. The number is 215-278-9411. Again, 215-278-9411. And we just might share it on a future episode. Make sure you leave your name. Okay. We’ll be back next week with a brand new episode.

Hosted by Georgia Sparling and Jon Watts.

Original music by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Edited by Georgia Sparling.

Mixed and mastered by Studio D.

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Referenced in this episode:

I loved this episode on Weird Quaker Names and the list is amazing. While I’m writing though I want to affirm your style, Georgia. Your enthusiasm, curiosity, kindness, and excellent reporting all come across in your voice. To me that’s amazing.

Keep it up! These are wonderful.

You make me giggle, toilet royal is my jam man

I loved this episode. There is a direct connection to the Quaker Tapestry which also resides in England. The fact that it was created by Quaker women from around the world and youth speaks to the roots of the ongoing practice of needle work among Friends women

I’m surprised by the surprise that’s expressed around the list of names — it was very common in early American culture to give children devotional names like Charity, Comfort, Temperance, Thankful et al, and family names are still often given to both girls and boys, especially in northeastern WASP families. In terms of the decorative artwork, I wonder if Ms. Rosner was able to map the creation of the more colorful and extravagant work against the obviously privileged background of the girls who created them, and where those families ended up in the 18-19C divisions over Quietism, worldliness, and eventually the 1827 Separation.

I loved them all! Great work!