The Grimke Sisters: How Two Southern Slave-Owning Quakers Became America’s Fiercest Abolitionists

Sarah and Angelina Grimke were unapologetically anti-slavery and pro-women’s rights. Their convictions were driven by their faith in God, yet it got them booted from Quakerism, made their name a curse among their Southern peers, and even caused controversy among fellow abolitionists.

The Grimke sisters made history, yet their names have largely been forgotten. Today, we introduce you to these unlikely abolitionists.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Want to contribute to upcoming show? Leave us a voicemail at 215-278-9411 and let us know what the term “conscientious objector” means to you.

Tell us your thoughts below!

Download the transcript and discussion questions.

Georgia Sparling

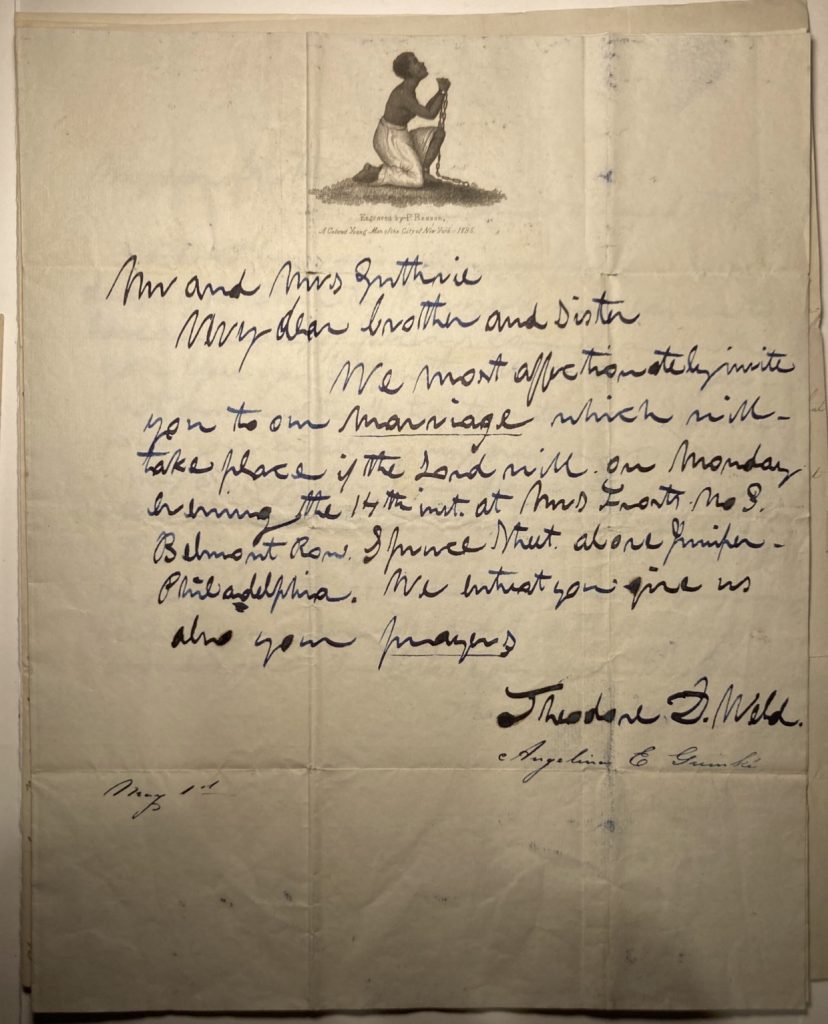

It’s May 14 1838, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the heavyweights of the abolition movement have gathered for the wedding of Angelina Grimke and Theodore Weld. She a Quaker, he a Presbyterian. Angelina’s sister and fellow abolitionist Sarah is there too, of course.

And this wedding like most things the Grimke sisters have done in recent years has caused quite a stir. They’re just so very unladylike.

Of course, the Quakers are not happy that one of their number is marrying outside of the fold. But that’s not the only detail out of the norm. Again, it’s 1838, 23 years before the Civil War. Yet, the wedding cake is baked with free trade sugar. The groom signs away rights to his wife’s assets, and in her vows, the bride omits the usual promise to obey her beloved. Overseeing the ceremony are not one but two ministers, neither of them Quaker. Even stranger, one is black and one is white.

The guestlist is also mixed. In attendance are formerly enslaved people, once the property of the bride’s family in Charleston. There is an abolitionist newspaperman named William Lloyd Garrison, and there’s even a man sporting a long flowing beard that he’s vowed to cut only when American slavery has come to an end.

This is the sisters’ penultimate public event. In a few days, Angelina will deliver an incendiary speech surrounded by an angry mob. And then Sarah, Angelina, and Theodore will almost completely disappear from the abolition movement.

Intro

Thee Quaker Podcast: story, spirit sound

Georgia Sparling

I’m Georgia Sparling.

Jon Watts

I’m Jon Watts.

Georgia Sparling

So how’s it going, Jon?

Jon Watts

Oh, it’s going great. Is it time for another history episode?

Georgia Sparling

It is.

Jon Watts

Awesome. What are we talking about today?

Georgia Sparling

Well, so if you ask a random person on the street, what they know about Quakers. What do they say?

Jon Watts

Well, so we did this for the podcast trailer. And I’m assuming you mean something other than Quaker Oats.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, the Quaker Oats is a given. So something other than the oats.

Jon Watts

Okay, so yeah, right. So a couple people mentioned silent worship, but I’d say a common thread was that most of them talked about our history.

Georgia Sparling

Right, like the general public, myself included, doesn’t really know a ton about Quakers today. But there is sort of this collective consciousness, at least in the States, about certain aspects of Quakers in American history.

Jon Watts

Right. Yeah, that makes sense. There’s a couple of really visible things that we’re known for, like founding Pennsylvania. And there’s also some political stances we’ve taken as a group like I’m thinking in particular, of abolition of slavery and participating in the Underground Railroad. Yes, exactly.

Georgia Sparling

Abolition, right.

Jon Watts

So that’s a complex topic, right? It’s not just cut and dry. All Quakers were abolitionists. In fact, lots of the conversation today around it is that it actually wasn’t very simple.

Georgia Sparling

Nothing ever is. I mean, there were factions and arguments, and it took a while for all Quakers to get on board with the anti-slavery movement. And that’s why today I want to tell the story of the Grimke sisters. It’s a story of some really unlikely abolitionist who were Quakers for a while.

Jon Watts

This is one that I don’t really know much about. So what was it that made them unlikely abolitionists?

Georgia Sparling

They were women at a time when women had very little agency, they couldn’t vote. They were also women from the South where they had little to no access to anti-slavery rhetoric, and they came from a religious but slave owning family.

Jon Watts

Okay, I have so many questions, but I’m sure you’ll get to them in the episode, so, so let’s do it.

Georgia Sparling

Today, you’ll hear from two women who are very enthusiastic Grimke historians. I’ll let them introduce themselves.

Louise W. Knight

My name is Louise W. Night. And I’m a biographer and historian, based in Evanston, Illinois, and I’m a visiting scholar in the Gender Studies and Sexuality Program at Northwestern University.

Georgia Sparling

Louise has written two biographies on Jane Addams.

Louise W. Knight

And now I’m working on a biography about the Grimke sisters that will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the next couple of years, and what drew me to the Grimke sisters was their ability to grow and change in increasingly radical directions, which for any biographer, at least, to me seems like a perfect story to capture in a book.

Georgia Sparling

And then there’s Lee Ann Bain.

Lee Ann Bain

I’m a tour guide here in Charleston, South Carolina, and I do the Grimke sisters walking tour, among other ones.

Georgia Sparling

Okay. Remember, Louise is the author. Leanne is the tour guide. Let’s get started.

Georgia Sparling

Honestly, Sarah and Angelina Grimke are some of the most unlikely abolitionist that America has ever produced. To understand how and why they became ant-slavery advocates, it’s important to understand where they came from. Let’s start with their dad. Here’s Lee Ann:

Lee Ann Bain

He was the Supreme Court justice for the chief justice for the state of South Carolina. He was one of the gentlemen that ratified the US Constitution for the state of South Carolina. He was our mayor of Charleston for a couple of terms. He sat on the House of Representatives.

Georgia Sparling

The Grimkes had a home in town, plus a country estate and a cotton plantation, all populated by enslaved Africans. For the girls, Sarah, who was born in 1792, and Angelina, the youngest Grimke, born 12 and a half years later, slavery was a completely normal institution. In fact, boats arrived full of enslaved Africans often children, a mere 100 feet from their front door in Charleston. They would surely have heard the cries of these strangers who had arrived in a strange land, sick, emaciated and chained. Some of them ended up in the Grimke household, and it was not a happy home.

Lee Ann Bain

Mrs. Grimke was very distant, very aloof with her children. They describe it as like when she gives them a kiss. It’s really out of motherly duty instead of motherly love, and she was into slavery. She thought that was there was nothing wrong with it.

Georgia Sparling

Lee Ann says Mrs. Grimke was a harsh master, her religious leaders had taught her that she had every right to be that way.

Lee Ann Bain

If there was a book on the table, and you could easily grab the book, she would, you know, ring her bell and have her slave come into the room and hand her that book. And she would walk around the house with a short little whip and was probably, you know, maybe six inches. And if she thought that person rolled their eyes or didn’t pick up the crumbs, whatever their offense was, she whipped them right then and there. And she had these whips strategically placed around the house.

Louise W. Knight

And clearly, that experience was partly what shaped them.

Georgia Sparling

That’s Louise again.

Louise W. Knight

However, many, many people including their brothers and sisters witnessed the same kind of thing and didn’t become immediate abolitionists. So it’s really not the main explanation. Quakerism was definitely part of it. And part of it was, I think, they will they were brilliant women, and they, their minds were strong.

Georgia Sparling

Sarah and Angelina had very different personalities. Sarah is a born nurturer, and she’s a mother figure to Angelina.

Lee Ann Bain

She’s got a heart of gold. You know, I mean, she’s very compassionate. She internalizes a lot of things.

Georgia Sparling

Sarah is still effectively a kid herself when she first begins to understand how horrific slavery is. It’s around this time that she’s given her first and only slave, an African child named Dinah.

Louise W. Knight

She was probably 9 or 10. And the idea was, Sarah was going to become a debutante at age 15. She was to train this young child to be her lady’s maid.

Georgia Sparling

We know from Sarah’s writing that Dinah was half starved and afraid to eat when she arrived at the Grimke household. Sarah was able to coax her to eat, and she even tried to teach Dinah to read until her father found out and forbade it. We don’t know much else, but by the time Sarah is 16, we know that Dinah has died.

Lee Ann Bain

When you go back and read Sarah’s letters and things like that. Dinah makes her mark on Sarah, and Sarah will write and talk about her for the rest of her life.

Georgia Sparling

Dinah’s death changes Sarah, but it takes many more years for her to denounce slavery. Angelina is perhaps even a harder case.

Lee Ann Bain

Angelina, on the other hand, is just like Mrs. Grimke growing up. Mrs. Grimke would call those enslaved in her house horrible, nasty names that I don’t repeat today. And Angelina will talk the exact same way.

Georgia Sparling

That is until her nanny, an enslaved woman, confronts Angelina about her derogatory language. She stops using it, but Angelina still doesn’t have any problem with slavery. Where Sarah is kindhearted, Angelina is headstrong and stubborn.

Georgia Sparling

This sisters are raised in a religious household, but it’s also one where questions and debate are welcomed. Their father is, after all, a lawyer.

Louise W. Knight

They had debates in the house. They argued about what is what is the basis for your conclusion, defend your point. And this was a great strength for the sisters to be raised in right? Because they were free to make up their own mind.

Georgia Sparling

This gave the sisters freedom to formulate their own beliefs. They were also coming of age during the Second Great Awakening when it wasn’t strange for Episcopalians to become Presbyterians to become Baptists. Both sisters experimented with different denominations. But Sarah is the first of the sisters exposed to Quakerism. When she’s in her late 20s, she goes with her dad to get medical care in the North. And while they’re there, they stay in several Quaker homes. But it’s not an immediate love match.

Louise W. Knight

She thought Quakers were fanatical because of course they thought slavery was a sin. Nobody in Charleston in Sarah’s world approved of Quakers.

Georgia Sparling

Judge Grimke dies while they’re up North, and on the boat ride home, Sarah meet some upper crust Quakers who tell her more about their faith. They leave her with some Quaker literature, and in it she reads about the Quakers stance on slavery — against — and their stance on women ministers — pro.

Louise W. Knight

That was like a crazy idea. There are many reasons she became a Quaker, but that was that was not small. That was a big one.

Georgia Sparling

A few years later, Sarah moves to Philadelphia to further explore Quakerism and to escape slavery. We hired a couple of voice actors to read portions of the sisters writing and speeches. What you’re about to hear is an excerpt written by Sarah for a book that she, Angelina, and Theodore Weld would assemble many years later.

Sarah Grimke

As I left my native state on account of slavery, and deserted the home of my father’s to escape the sound of the lash and the shrieks of tortured victims, I would gladly bury in oblivion the recollection of those scenes with which I have been familiar. But this may not, cannot be. They overcome my memory like gory spectres, and implore me with resistless power, in the name of a God of mercy, in the name of a crucified savior, in the name of humanity, for the sake of the slaveholder as well as the slave to bear witness to the horrors of the Southern prison house.

Georgia Sparling

Sarah immerses herself in the Arch Street Meeting in Philly. And of course, she tries to convince Angelina to become a Quaker too. On one visit home she brings a female Quaker minister with her. Angelina is impressed. She’s been on a faith journey of her own and been kicked out of the Presbyterian Church. Quakerism suddenly becomes much more appealing to the headstrong Angelina, but not only because women had more of a voice in the Quaker meeting.

Louise W. Knight

So, I’m pretty sure that part of what really drew them to the Quaker faith was also its quietude. Its love of silence, its belief in gentleness, its belief that you shouldn’t raise your voice. These are all very comforting to to these two women who did not feel at all peaceful in the house they grew up in. And I think that’s partly what drew them and also the message of love, which of course, every denomination has, every Christian denomination has, but the Quakers are especially insistent upon it permeating your every waking moment, you know, that your whole being should be gentle and loving, all the time, in how you greet people, how you listen to people, all those things I think were soothing to the sisters given their upbringing.

Georgia Sparling

Angelina finally moves to Philadelphia is 1829. Eight years after Sarah joins the Arch Street Meeting. This sisters still are not abolitionists yet, but they become strongly anti slavery. Surprisingly, they find that the abolition movement within Quakerism isn’t quite as robust as they were led to believe.

Louise W. Knight

Each of them arrives in the Quaker community in Philadelphia thinking alright, this is the one religion that thinks owning human beings is a sin. But what they, of course, the times had changed when the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting was supporting the gradual abolition movement it was the 1780s.

Georgia Sparling

Gradual abolition was just like it sounds, a total cop out.

Louise W. Knight

And that said, at the moment this law takes effect. Any enslaved mother, whose child is born after that date, will become free when they reach the age of X: 21, 27, 28 whatever it was. So it freed no one.

Georgia Sparling

The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting was comprised of wealthy Quakers whose assets were all tied up in the American economy, much of it powered by slavery. Plus they had slave owning friends. As an alternative, many Quakers signed on to the colonization movement.

Louise W. Knight

Which meant any slave owner who wanted to could send the slaves of his or her choice to Africa to Liberia, and then also we’ll send a we’ll invite as many free Black people as possible to go to Liberia to and basically we’ll, the argument was we’ll just gradually rid the country of Black people.

Georgia Sparling

Sarah seems to have considered this option for a time, but she’d befriended the Douglass family, the one black family that worshiped at the Arch Street Meeting.

Louise W. Knight

They had to sit on a separate bench at the back.

Georgia Sparling

Sarah would sit on that bench with them. And there is correspondence between Sarah Douglass and Sarah Grimke that shows the former warning her friend off of the colonization movement. So the sisters were searching for ways to help. And it was clear that gradual abolition and the colonization movement were total smokescreens.

Louise W. Knight

And it is in that context of the immediate abolition movement emerged.

Georgia Sparling

Immediate abolition was a movement to eradicate slavery right now. Angelina is on board. She has also been attending abolitionists meetings and she writes a letter that will thrust her into the spotlight, close the door on Sarah’s dreams and estrange the sisters from Quakerism forever. That’s after the break.

Erin Bates

Hey, Jon,

Jon Watts

Hey, Erin, how are you?

Erin Bates

I’m good. How are you today? Can you hear me? Yes.

Jon Watts

All right. Thanks for taking a second to talk with me.

Erin Bates

Yeah, for sure.

Jon Watts

So you and I have been in touch a lot recently because we’re working together on the Intermountain Yearly Meeting gathering in Colorado this summer. And at some point in that process, you mentioned that you were relatively new to Quakerism and that my work had played some role in that. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit more about that story.

Erin Bates

Yeah, absolutely. So I first went to a Quaker meeting in November of 2021. And before that, I was part of a very, very conservative, fundamental evangelical Christian church, and my partner was not. And we were trying to figure out how to mesh our beliefs together. And he asked me to go to a Quaker meeting with him. So I opened my heart a little bit to the thoughts of Quakerism. But I didn’t know if I felt comfortable going to an actual meeting with people.

So I started looking on the internet about, you know, what is Quakerism. And very quickly, I found Quaker Speak. So, I remember very specifically, the first one that I watched was “Are Quakers Christian?” And there was an interview that said, in Quakerism, there are no lay people because we’re, we all have God in us. And I thought that was a really beautiful sentiment. This really started kind of opening my eyes to that the Quakers each had their own faith, and that that was okay. And that the group as a whole was not purposed to change my faith or tell me what to believe, but that rather, it was a guide to help learn how to live in this. I think the video might have even called it a “dynamic spiritual presence,” where we’re focused on community, and we’re focused on helping people in the world right now. That’s what convinced me to go to a meeting.

And so I went to my first meeting at Mountain View Friends Meeting with my partner. We heard some of the, I think it was the Peace and Social Justice Committee, they stood up and they said there was a recent shooting at a Jewish synagogue. And that Mountain View was looking for people to volunteer to go stand outside of a Jewish synagogue on one of their upcoming Holy Days, because they needed a peaceful nonviolent presence, so that the Jewish people could go and worship and peace, and that just sealed the deal.

Jon Watts

Thank you so much, Erin. I appreciate you doing this spontaneously.

Erin Bates

My pleasure, Jon. Have a good rest of your day,

Jon Watts

Okay, you too.

Jon Watts

If you’d like to support our work, we want to keep having rich conversations, like the ones that Erin discovered online that led her to Mountain View Meeting. This weekly Quaker podcast that you’re listening to right now is listener supported. So you can make a big difference by going to Theequaker.org and pledging a monthly donation to our Patreon. Thanks so much for your consideration. And now back to Georgia.

Georgia Sparling

Angelina is 32 years old in 1835 when she goes viral…in 19th century terms. It’s been six or so years since she moved to Philadelphia and about 14 since Sarah headed north. Conceivably this sisters could have just kept living a quiet Quaker life and quietly supporting abolition, but that’s not really Angelina’s style. Remember, she’s kind of a rebel. So she sends a letter to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison after riots erupt in Boston, and he publishes that letter in his newspaper, The Liberator, no doubt knowing that the Grimke name carries weight.

Angelina Grimke

The ground upon which you stand is holy ground. Never, never surrender it. If you surrender it, the hope of the slave is extinguished, and the chains of his servitude will be strengthened 100 fold. But let no man take your crown and success is as certain as the rising of to-morrow’s sun.

Georgia Sparling

Angelina had already joined the Anti-Slavery Society, but this letter thrusts her into the spotlight.

Louise W. Knight

And part of her I’m sure felt better, you know, like, alright, I’m owning it. And it precipitated her into the abolitionist life. Because she became really famous from that letter.

Lee Ann Bain

The Quakers and Sarah are like telling Angelina, denounce this letter. He shouldn’t have he didn’t have the right to publish what she wrote to him in his newspaper and Angelina doesn’t.

Louise W. Knight

Now one of the big questions is, why was Sarah opposed to Angelina writing that letter? And it was not because Sarah was opposed to the immediate abolition movement. What bothered her about Sarah Angelin’as letter was that it really upset and disturbed the leadership of Arch Street Meeting where Sarah was trying to become an approved minister.

Georgia Sparling

As a kid, Sarah had wanted to be a lawyer. Her father shot her down. But after a spiritual conversion experience, Louise says that Sarah immediately felt called to be a minister, something that obviously wasn’t going to happen in most churches at the time, except for among the Quakers. Now for Sarah to embrace her sister’s radical abolitionism, which the Quaker leadership was against, she would lose another dream to become a recorded Quaker minister who could travel beyond her own meeting to speak because obedience

Louise W. Knight

was very important under the rules of the discipline. And Angelina had not, she was going out on her own right?

Georgia Sparling

But Angelina won’t back down. Indeed, she felt that as a Christian she couldn’t. Next she writes the “Letter to the Women of the South.” It’s not really a letter. It’s 36 pages long and appeals to her fellow Southern women as Christians, laying out a biblical argument for denouncing slavery. And Angelina felt compelled by God to write it.

Louise W. Knight

It was a spiritual crisis. She spent the night of that crisis, weeping and praying on the floor of her bedroom.

Angelina Grimke

Above all, try to persuade your husband, father, brothers and sons, that slavery is a crime against God and man, and that it is a great sin to keep human beings in such abject ignorance; to deny them the privilege of learning to read and write…

Georgia Sparling

Angelina sends the letter to the American Anti-Slavery Society. They publish it and distribute it throughout the South. Sarah begins writing too not long after the “Letter to the Women of the South,” Sarah pens her own missive, but she appeals to ministers.

Sarah Grimke

The system of slavery is necessarily cruel. The lust of dominion inevitably produces hardness of heart, because the state of mind which craves unlimited power, such as slavery confers, involves a desire to use that power. And although I know there are exceptions to the exercise of barbarity on the bodies of slaves, I maintain that there can be no exceptions to the exercise of the most soul withering cruelty on the minds of the enslaved.

Georgia Sparling

The sisters spend time in training with other abolitionist and then they begin touring the north, visiting small groups of women in their parlors to speak not only about abolition but about the rights of women. For the sisters, these two issues go hand in hand. All this time the sisters knew they were risking dis-ownment from their meeting, but they also knew that they had not technically disobeyed any Quaker rules. Still, their stance on slavery had begun to alienate them from many of their Quaker Friends.

Louise W. Knight

They both lost a lot of Friends, most of their Friends. Some of the Quakers in New York were still friendly to them and would invite them for meals but would not put them up when they needed a place to stay.

Georgia Sparling

They keep traveling and writing and speaking. Angelina especially gets attention for her speeches, so much so that she’s the first woman invited to speak before an American legislative body, ever. She addresses the Massachusetts State Legislature:

Angelina Grimke

Angelina Grimke

I stand before you as a southerner, exiled from the land of my birth, by the sound of the lash, and the piteous cry of the slave. I stand before you as a repentant slaveholder. I stand before you as a moral being, endowed with precious and inalienable rights, which are correlative with solemn duties and high responsibilities; and as a moral being I feel that I owe it to the suffering slave, and to the deluded master, to my country and the world, to do all that I can to overturn a system of complicated crimes, built up upon the broken hearts and prostrate bodies of my countrymen in chains, and cemented by the blood and sweat and tears of my sisters in bonds….

Georgia Sparling

Only a portion of Angelina’s words survive today, but we know that she also addresses the men with a push towards equal rights for women. Angelina speech is in February 1838, only about three months before her wedding to fellow abolitionist Theodore Weld. The two already had a mutual attraction simply through reading each other’s abolitionist publications. When they finally meet in person in 1836.

Louise W. Knight

They both admit that’s when they each locked eyes and fell in love. Because they already were in love from the letters. There was a real meeting of the minds.

Georgia Sparling

It’s two years before they get married, in part because the Grimkes are traveling for the cause. When they do finally get married, their wedding causes quite the stir. There were posters printed about the audacious “amalgamation” of races. That was a dirty word at the time.

Georgia Sparling

The wedding took place the same day as the dedication for Pennsylvania Hall. That was no coincidence. This new building in Philadelphia was constructed to give anti-slavery activists a place to speak. As Theodore Weld said “it was a place consecrated to free discussion and equal rights.” Two days after their wedding, Angelina spoke at Penn Hall as an angry mob of colonizers gathers steam outside. As she speaks, people are throwing rocks and yelling, but it doesn’t faze Angelina.

Angelina Grimke

What is a mob? What would the breaking of every window be? What would the leveling of this hole be any evidence that we all wrong? Or that slavery is a good and wholesome institution? What if the mob should now burst in upon us, rake up our meeting and commit violence upon our persons? Would this be anything compared to what the slaves endure? No, no.

Louise W. Knight

There were lots of African American women there, lots of white women there, and they walked out arm and arm to protect the Black women from the violence of the mob. And the next day, Pen Hall burned down.

Georgia Sparling

While the authorities watched. This was also pretty much the last time Angelina spoke publicly,

Louise W. Knight

but it wasn’t that she knew it at the time. And the idea was that, you know, Theodore bought a farm outside of New York City at Fort Lee, and the sisters were going there to rest they had been working very hard, living always in other people’s houses ever since they left Charleston. And so they were really excited to have a home of their own that they were going to go nest for a few months and rest and then they were gonna go back on the road.

Georgia Sparling

But it wasn’t to be. Angelina, who is in her mid 30s, gets pregnant and has three children and a few miscarriages in quick succession. She gets a prolapsed uterus and is not well for some time. Both Theodore and Sarah dissuade her from traveling. Both sisters wanted to keep writing, it just doesn’t happen not in any significant way. Plus the family needed to work. Their Charleston inheritance had largely run out.

Georgia Sparling

So the sisters really only spent three years as public activists. There were certainly fellow abolitionist calling on the sisters to get back out in the field. But Louise also points out that there wasn’t the precedent we have now to become a career activist.

Louise W. Knight

We all feel disappointed the sisters wouldn’t go back on the road, especially Angelina with all that talent.

Georgia Sparling

Sarah, Angelina, and Theodore do collaborate on a tome of a book called “Slavery As I Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses.” It details the horrors of slavery through firsthand accounts, including letters from both sisters.

Harriet Beecher Stowe use the book as a reference for her novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Later they discover that they have nephews, Archibald and Francis, the sons of their deceased brother and an enslaved woman named Nancy Weston, and for the rest of their lives the four maintain a close relationship. This sisters helped them attend Harvard and Princeton. And it’s Francis and Archibald, not Angelina and Theodore’s children, who ended up carrying on the work of fighting for equality for African Americans. Of course, their mother and Nancy Weston, who really pushed for the boys education played a large role in the men that they would become. Archibald goes on to become a lawyer. Frank becomes a prominent Presbyterian minister, and they both helped to found the NAACP.

Jon Watts

Georgia, wow. Thank you so much for that story. Um, I’m actually a little embarrassed. I didn’t know more about the Grimkes before now. But you know, I really appreciate your work on this.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, these women were such firebrands, and it would have just been so easy for them to have stayed within their safe, wealthy upbringing. And I think the image that I’m really left with is the one of Angelina weeping and praying all night because she’s so convicted about writing this letter to her fellow Southern women.

Jon Watts

Yeah, that moment really stuck out for me, too. That was that’s a powerful image.

Georgia Sparling

I was also really fascinated about how the sisters commitment to abolition really trumps their Quaker faith in a way. Like they were really committed to Quakerism, they spoke using the traditional “thee” and “thou,” they wore plain dress, their closest friends were capital F Friends. But at the time, it seems many Quakers weren’t quite yet willing to take as strongest stance against slavery as they were.

Jon Watts

Right. They were they were even outliers within Quakerism. Like they were pushing the envelope. So, so what happened with that? What was there? What happened with their Quakerism?

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, well, they really toed the line for a while. But the wedding was a disownable offense.

Jon Watts

The wedding, how so?

Georgia Sparling

At the time, it was against the rules for a non-Quaker to marry a Quaker, so Angelina got kicked out. And it was also against the rules for a Quaker to witness such a wedding and so Sarah got kicked out.

Jon Watts

Just to witness the wedding. Wow, it was so easy to get kicked out of Quakerism back then. I’m just happy that I got married in the 21st century.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, there’s a lot to be grateful for about the 21st century.

Jon Watts

Absolutely. And at the same time, and you know, despite all the messiness that you highlighted in this story, there’s also something there that’s kind of working on me, you know, like, what is the modern equivalent? What’s the justice issue in our day that Quakers might be wrestling with?

Georgia Sparling

Right, like, who are the modern Grimke sisters that are kind of going against the grain?

Jon Watts

Yeah. Who are the modern grumpy sisters?

Georgia Sparling

Well, maybe we’ll find the answer to that in a future episode.

Jon Watts

Yeah, fair enough. Thanks, Georgia.

Georgia Sparling

Thanks, Jon.

Thanks for listening. And a special thank you to Lee Ann Bain and Louise W. Knight, as well as to Jim Fussel, who provided historical background for this episode. Thank you also to the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan for sharing letters from their extensive collection of correspondents from the Grimke and Weld families.

Our voice actors were Kelly Lindsay and Kristen Osbourne.

So what about Angelina and Sarah’s story resonates with you? Head over to our website to share your thoughts. That’s Quaker podcast.com. And while you’re there, you can also download a transcript from this episode. You can subscribe to this show. Learn more about today’s guests and see Angelina and Theodore’s provocative wedding invitation.

This episode was produced by Jon Watts and me, Georgia Sparling. Jon also wrote the music for this episode.

Thee Quaker podcast is part of Thee Quaker project, a brand new Quaker media organization whose focus is on lifting up voices of spiritual courage and giving Quakers a platform in 21st Century Media. If you want to support our work, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter. We’re a brand new project and every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way. We make this show for you. So thank you for listening.

Now that you’ve heard from us, it’s time for us to hear from you. Tell us what it means to you to be a conscientious objector. Please give us a call and leave a voicemail at this number. You ready? 215-278-9411 Let me repeat that 215-278-9411 If you try the number before and couldn’t get through. That’s probably because I gave you the wrong one on a previous episode. My apologies. We do want to hear from you. So please give us a ring. Please try to keep it to a minute and we might share your response on a future episode.

Next week on the podcast. What happens when your calling seems to fly in direct opposition to your meeting?

Recorded and edited by Jon Watts and Georgia Sparling

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Referenced in this episode:

- Learn more about Louise W. Knight and her research into the Grimkes on her website.

- Take Lee Ann Bain’s Grimke Sisters Tour through Charleston.

- Read more about the ill-fated Pennsylvania Hall.

There is a fantastic novel about the Grimke sisters, called the invention of wings. It would be wonderful as I have some suggested previously if when you do a topic, you could link books to it in support of the bookstore and FGC. If you do anything more about early friends, I would love to be interviewed to talkThe Kendal Sparrow.

Yes, Sue Monk Kidd’s novel, Invention of Wings, about Sarah Girmke and an enslaved person Kidd calls Hetty is a wonderful read. While almost all of the book, as you would expect, is fiction it still gives readers the sense that they have learned actual history. That is the power and appeal of historical fiction. To be sure there were no such letters between Sarah and a person named Hetty. Some of the horrifying details about how enslaved people were treated, though, are accurate.

My Friend lent me a copy of the Kendal Sparrow and I found it fascinating. As well researched historical fiction I learnt so much about the context in which early Quakerism spread. I highly recommend it. I was drawn to it as I ‘chanced’ upon the Quaker Tapestries in Kendal in 1994, was inspired and returned 20 years later, as a new Quaker, to volunteer. (Lisa, GuriNgai- Darkinjung Country, NSW, AustralIa)

I’m glad you posted this I did not learn anything about these ladies in my traditional “great men” history classes

I was wondering when these two sisters would be recognized. I have read about them and they always intrigued me.

Your podcast is a great way for me to learn more about my Quaker forebears and learn more about modern day Quakerism. Thank you this work that clearly goes into this!

I had never heard of the Grimke sisters, thank you for the story. I’m not a member of the society of Friends, but have always greatly admired them.

I’m glad that I “stumbled” on this page. Perhaps can learn more about the two groups of Friends in the USA.