A Quaker Pacifist Joins the Military

Zachary Moon was raised in a Quaker Meeting full of anti-war protesters. Then he felt God calling him to join the military as a chaplain. In the following months and years he had to wrestle with that leading and the response of his family and community.

On this week’s episode, we ask, what happens when your calling seems to be in opposition to the thing that unites your faith community? And can you be a Quaker pacifist while wearing a military uniform?

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

Want to contribute to upcoming show? Leave us a voicemail at 215-278-9411 and let tell us about your first Quaker Meeting.

Tell us your thoughts on this episode!

Download the transcript and discussion questions.

Discussion questions:

- Zachary Moon says, “I think sometimes, in different kinds of human communities, we think we have to find stuff that we all agree on. And that’s the sturdy stuff.” How does that statement resonate with you?

- As a college student, Zachary’s idea of the Quaker faith changed from an isolated island to a living, breathing whale. In what ways can you and/or your community “embrace the whale”?

Georgia Sparling

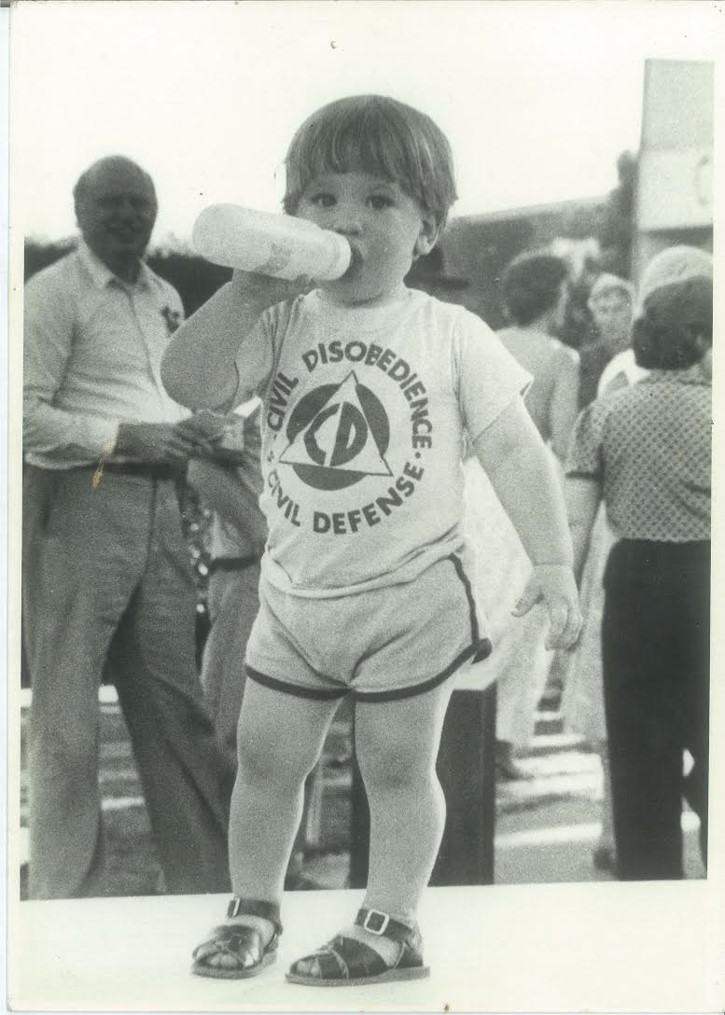

For his entire life, Zachary Moon has been deeply embedded in Quakerism. He was a peacenik. He protested outside of prisons and a president’s house. He had a season of wearing plain dress — beard, suspenders, the whole thing. And he was the token young Quaker at his yearly meeting. And then Zachary felt called to join the military as a chaplain, which turned out to be its own kind of battle.

Zachary Moon

Gosh, I remember there was like a handful of people who thought that I was going to like Harriet Tubman folks like out of the military, like I was going to be like a secret agent who was going to like Underground Railroad folks like to be conscientious objectors.

Georgia Sparling

For others, there was no possible scenario where it was okay for a Quaker to join the military. One of those people was Zachary’s mom.

Zachary Moon

And that relationship was much more high stakes. I owe her everything. I am everything because of who she is. And she experienced it as a betrayal as the most shameful possible thing I could do in my life.

Georgia Sparling

Today, what happens when your calling is at odds with the identity that your community holds most dear?

Various

Thee Thee Quaker Podcast: Story, spirit sound

Jon Watts

all right, I’m ready when you are.

Georgia Sparling

Okay, I am too. Alright, you’re first.

Jon Watts

I’m Jon Watts.

Georgia Sparling

I’m Georgia Sparling. And today’s topic is a pretty timely one because it’s the day after Independence Day here in the U.S. It’s a day that’s full of patriotism. And when there’s lots of talk about the military and fighting and winning wars and that kind of thing.

Jon Watts

Yeah, and Quakers are, of course, notorious peaceniks. So you know, it’s not exactly our favorite holiday.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, that tracks. So but today, we’re going to talk about a Quaker guy who joined the military, but as a chaplain…

Jon Watts

chaplain, right. So so there’s actually there’s only one person I can think of who might be talking about, is it that’s Zachary Moon, right?

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, that’s him. And even though he didn’t join the military to become a soldier, his decision caused him a lot of inner turmoil, and it confused the people in his community, like, especially his mom.

Jon Watts

Okay, yeah, I can imagine. I’m so I actually interviewed Zachary about this story before. And it was when I was releasing weekly Quaker YouTube videos. And I interviewed him and posted it in a video and called it “How Can A Pacifist Support Our Troops?” And, and, you know, we got a lot of comments on that video.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah. Like, what kind of comments?

Jon Watts

Well, you know, this is an issue that Quakers feel really passionately about from different angles. So I’ll just give you one example. A commenter said, “it is not possible to uphold our peace testimony and wear a uniform.” And then that same person went on to say, you know, to ask what meeting Zachary is part of and to call him, well, he called him “a disgrace to the Religious Society of Friends.”

Georgia Sparling

Wow, that’s pretty intense.

Jon Watts

It’s intense. Yeah, Quakers care a lot about peace. But, you know, that gets expressed in a lot of different ways.

Georgia Sparling

Right, yeah. And we talked about this a little bit in episode two, where we talked about George Fox, and you know, he really was the first person to push back against participating in violence or war.

Jon Watts

Sure. Yeah, it goes, it goes all the way to our beginning. I mean, growing up Quaker, this was something that was ingrained in me from the time I was a little kid, you know, and really violence of any kind, like, in speech or in physical action. It’s something that most Quakers I know, work really hard to avoid.

Georgia Sparling

But being a chaplain, that that’s a lot different than becoming a soldier.

Jon Watts

I mean, yeah, some would make that argument. And there are a lot of stories throughout history of Quakers being conscripted into the military, but then avoiding direct participation on the front lines by, you know, driving ambulances or doing desk jobs or something like that. But other Quakers have argued that any participation is wrong because the military is an organization whose entire purpose is violence. So those are the Quakers who you know, like many before them, would choose to go to prison before they would have Anything to do with supporting a war?

Georgia Sparling

It’s definitely got a lot of layers and nuance, more than I think I would have realized.

Jon Watts

For sure. Yeah.

Georgia Sparling

And I think that that plays out in today’s episode. So how about we go ahead and jump in?

Jon Watts

Let’s do it.

Georgia Sparling

The fact that Zachary Moon joined the Navy, even as a chaplain, will make sense, I think once we get into the story, but right up to the point where he felt that call, it was not something that he would ever have considered. Zachary grew up in the Berkeley Meeting.

Zachary Moon

So these were folks who had not been brought up in the tradition, but particularly kind of who Berkeley, California is, in the ’60s and ’70s and beyond. It was a place that was just thickly resonant with particularly the value of peace and the value of peace and antiwar kind of commitment.

Georgia Sparling

I want to emphasize that Zachary didn’t just grow up in the Berkeley Meeting. It was woven into the fabric of his daily life.

Zachary Moon

For much of my childhood, my family served as the caretaker of our local meeting. So going to Meeting for Worship wasn’t like a one day a week thing. So like the extended family that was wrapped around me raising me as a child were members of our Quaker meeting,

Georgia Sparling

When his parents split up, the Meeting told his mother, Laura Magniani, that they could do whatever they wanted, but the meeting got to keep Zachary. And he fit in well with this peace loving community. His mother was heavily involved in prison reform, he attended peace rallies and protested executions. Yet he also remembers having this niggling discomfort with what he saw as an avoidance of God talk in his meeting.

Zachary Moon

Peace was something that we all agreed with. So some folks would say, you know, Jesus was the Prince of Peace, right? So they bring some of that kind of Christianness to it. But other folks would say, you know, no, no, no, no, no, don’t bring Jesus around here. And usually, that was a kind of reaction, I think, that had to do in large part for many people’s upbringing, that Jesus had not been a benevolent, warm, compassionate, you know, fighter for justice. Jesus had been a bludgeon, Jesus had been a punisher, a source of shame and guilt and control. So let’s not talk about Jesus too much.

Georgia Sparling

Zachary described his early view of Quakerism as this isolated island in the middle of a whole lot of chaos. Yet, as he got older, he says he and other young Quakers began to see that differently. Zachary realized he wasn’t on a tiny island, he was part of something much more magnificent, something that was alive.

Zachary Moon

It was actually the back of this extraordinary whale that had just been like waiting for us in the middle of the ocean and was like, let’s move. Like, what’s under you is not a piece of rock. It’s like this magnificent living creature that wants to dive. It wants to move, it wants to migrate, it wants to change.

Georgia Sparling

He kept seeing this image, even as he got pushed back in his community about going outside of tradition.

Zachary Moon

But I don’t see that as a Quaker problem, like I see that truly as being a problem with every faith community I’ve ever come across is, are we going to keep this thing quiet? Are we going to keep this thing under lock and key?

Georgia Sparling

Zachary did what so many West Coast kids do. He went east for university to Vassar College.

Zachary Moon

In a little collapsed industrial town called Poughkeepsie.

Georgia Sparling

And you may be thinking, this is where he diverges from Quakerism. This is where he experiments with other religious traditions and faith. Nope.

Zachary Moon

While I was at college, my my faith, my sense of spiritual connection really went from being this kind of total, immersive thing like in terms of my environment, to being something that was like finding new depths to my soul and my sense of connection as well. And so I started doing some kind of like wild things like I started wearing Quaker plain dress every day my senior year of college, which at Vassar, which is a very secular environment, I think like freaked out everybody. They were like, Zachary, you wore that same thing yesterday. And I’m like, yeah, I’m gonna wear this every day. I mean, I got the mail order catalog, you know, from the plain dress and Amish folk. And then I stopped shaving and I let my beard just get shaggy, shaggy, shaggy.

Georgia Sparling

His senior year, as his courses wound down, Zachary travelled the country by bus and train to visit family and also to attend meetings for Friends General Conference. His plain dress drew a lot of attention on those trips and opened up surprising spiritual conversations.

Zachary Moon

And at first, you know, you feel a little embarrassed, but then you’re like, oh, my goodness, this is like would never happen if I was just wearing, you know, my hoodie and jeans. Like people would come up to me and start talking about God. And I really cherished the gift of that, to just talk with other people about what was God in their life.

Georgia Sparling

This was the early aughts, post 911, and religion was sometimes a fraught topic. Yet here he was having frank conversations about God wherever he went.

Zachary Moon

But ultimately, I laid down that practice because I didn’t want it to become static. I didn’t want to become the guy who wear suspenders. I needed to to try to honor the whale, you know, that was swimming and wanted to move and wanted to change. And I think actually, in retrospect, that was actually kind of like the first masterclass in chaplaincy.

Georgia Sparling

As a college graduate, Zachary worked with a couple of nonprofits back out West. One of those was a pacifist organization in the Nevada desert that challenged the use of nuclear weapons. Yet, even in this good work, he felt restless.

Zachary Moon

When I would be quiet, you know, going to Quaker meeting and praying at home, you know, whenever I would be in any kind of contemplative open space. What kept coming up was working with people who are in the military, doing ministry with people who are in the military. Now, like, talk about absurd, like, talk about, like, where does that fit like that was the weirdest possible message for a Quaker kid from Berkeley, California.

Georgia Sparling

He didn’t talk about it yet. Instead, he started going to seminary, which was also a little weird for a liberal Quaker kid. And he also did field work at a veteran’s hospital.

Zachary Moon

That was also like, viewed with suspicion. They were sick, they were broken, they were traumatized by their war experience. And so caring for them was like still tolerable.

Georgia Sparling

Again, this felt like good work. But he knew he was still being asked to do more. But anytime Zachary tried to broach the topic of working with the military, he was met with opposition.

Zachary Moon

And what I kept hearing back from community was I mean, really what amounted to Quaker God doesn’t want you to do this. But then immediately, the question came to mind, well, what does God God want me to do? And then the feedback to that was, we don’t know about God God, we know about Quaker God, and Quaker God doesn’t want you to do this. And that’s all I got, right. And different versions of that feedback. The kind of scope and theology of our understanding of God was very much restrained within, you know, particular markers within our tradition. And the biggest piece of that was, we’re all here for peace. And there won’t be involvement and engagement directly with people who were in the military. That, that didn’t put any of this to rest, right, because I didn’t feel like this was Quakerism telling me to do this. It felt like there was something bigger in our universe that was, had a hold of me and was working, working me pretty hard. In August of 2011, I raised my hand and I commissioned as a chaplain in the United States Navy.

Laura Magnani

His dad and I when he was teeny tiny and, uh, we used to say, well, I wonder what he’ll do to rebel, you know, and we thought about green hair and tattoos and things like that, but we didn’t think about this. And of course, he wasn’t rebelling, but the idea that he would join the Navy just never crossed my mind. Especially because he’s such a, he is such a pacifist. He still is a pacifist.

Georgia Sparling

That’s Laura Magnani, Zachary’s mom. She and Zachary both say they’ve always had a close relationship, which is why it was particularly difficult for both of them when he joined the military.

Laura Magnani

I think he postponed telling me that as long as he possibly could, which was probably smart, because it was a very big blow.

Georgia Sparling

Laura remembers being at her son’s wedding and trying to convince a chaplain friend of his to talk Zachary out of going into the Navy.

Laura Magnani

And it was countered everything that we believed in everything that we had worked on.

Georgia Sparling

Laura, had come to Quakerism in college, and one of the first things she did was join a year long course on non-violence. Laura has spent most of her adult life working for Quaker organizations, starting with the Friends Committee on Legislation of California, and then 32 years with the American Friends Service Committee.

Laura Magnani

In my work with the AFSC, I worked on the criminal legal system. I was a prison abolitionist, and I worked on prison issues. So I was I had quite an intimate relationship with prison chaplains.

Georgia Sparling

Yet she still couldn’t reconcile the idea of her son becoming a Navy chaplain.

So I definitely had it had a real learning curve. And I feel like I wasn’t there for him in the beginning, you know, I really feel like he was going through this very traumatic experience of trying to hear this call. And all of the negative voices that would come with it. And, and, and I wasn’t helping him with that, because I was dealing with my own trauma around it in the beginning. What I learned once he was was in it, and I mean, I was still hoping he would change his mind even when he was in boot camp.

Georgia Sparling

But that isn’t what happened. Zachary was getting all kinds of responses from family and from friends in his meeting.

Zachary Moon

Like some folks were like, wow, that is, that is weird, but I like weird things. So maybe this is okay. And then there were, gosh, I remember there was like a handful of people that I crossed paths with who thought that I was going to like Harriet Tubman folks, like out of the military, like I was going to be like a secret agent who was going to like Underground Railroad folks. Like to be conscientious objectors. Like that’s that that was like my sneaky plan that I that I couldn’t say out loud, but they were like, wink, wink. Yeah, that was like a secret double agent is going to be like, the pacifist to, you know, save people from themselves. And I was like, oh, gosh, that’s so that’s such a particular way of looking at this is not is not what this is.

Georgia Sparling

And although he’d felt a strong call to military chaplaincy, Zachary wasn’t prepared to act on that call by himself.

Zachary Moon

But where we were collectively in that moment was that there wasn’t a kind of sense of general readiness to discern that call. I knew I couldn’t trust this if I didn’t really have that space to test it in discernment. I needed clearness, like, in the most profound kind of way. I needed discernment, and I couldn’t do it by myself. I’d done everything I could possibly do. And it was a mess. It didn’t make any sense. It didn’t make any sense to anybody else. I had broken my mother’s heart. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do with any of this.

Georgia Sparling

So Zachary reached out to other Quaker meetings.

Zachary Moon

And then the most, another very unexpected, wonderful thing happened, which was I knew some folks were a part of a pastoral Quaker community, a programmed Quaker community in Metro Portland, Camas, Washington. What they said, you know, there are a couple of kids who grew up in this meeting who are serving in the military right now. They deserve a good chaplain. So we’ll sit with you and we’ll test this with you. And those folks didn’t know me from anybody. They just received this letter from a perfect stranger. That said, I’m out here in the wilderness and I need some warmth. They say come on around here, let’s see what God is doing. And that’s what we did.

Georgia Sparling

After the break, Zachary goes to boot camp.

Don Hutchinson

Hey Jon, can you hear me now?

Jon Watts

Hey, Don. Yeah, I can hear you serve. Yeah. So a week ago, you left this really sweet comment on our Facebook page talking about how my work had helped you in your spiritual journey. And I wonder if you could tell me a bit about it.

Don Hutchinson

Absolutely. I was watching the series and they in this Quaker family, and I was like, wow, that’s really interesting. I wonder what Quakers are about. That led me down a three-day rabbit hole of trying to figure out why I couldn’t be a Quaker. I was Googling at one point. I was like what have Quakers done that’s bad. And it was always coming up with articles from Quakers being self critical, like, oh, we could have done more to abolish slavery. Oh, we could have done more to be against the Vietnam War. I mean, it was always the self critical articles. I was so frustrated because I was like, What’s wrong with these damn Quaker? Besides, eventually, it led me to the Quaker speak videos. I mean, I was fully in it like lunch break at work I was watching Quakers videos, I go home and watch Quakers videos, it just felt so authentic.

Jon Watts

Awesome. So tell me about your first time going to meeting.

Don Hutchinson

Oh, absolutely. So it was Dayton Friends Meeting. And there were two messages given that day of meeting and the first one talked about reading the Bible. And the other one, I will remember till the day I die was from Alan McGrew. And he is a professor of geology from University of Dayton. And he was talking about how trees in nature work together as a community. And so from my first meeting, I was sold hook, line and sinker. I was like, you couldn’t pull me away from Quaker if you tried. I mean, to hear a message of faith, immediately followed by a more empirical argument, which also underlines the presence of Spirit in our life. I just couldn’t have been happier.

Jon Watts

If you’d like to support our work, please visit TheeQuaker.org. We need your help to continue telling these stories of spiritual courage. Together, we can build a meaningful voice for Friends on 21st century platforms, just like this one. Again, that website is TheeQuaker.org. Thanks so much.

Georgia Sparling

Welcome back. So I’m gonna bring Jon back on for a little mid episode debrief. So Jon, I know you are already familiar with Zachary’s story. But as you listen to him talk about the turmoil that he felt and also like the response he was receiving from his meeting. How does all of that sit with you?

Jon Watts

Oh, I mean, it’s, well, it’s such a rich conversation. Right. And it strikes at the heart of our commitment as Friends. And it brings up a lot of questions, you know, does does a commitment to non-violence mean that we don’t participate at all? In anything related to armed conflict? Like, I’m curious about Zach, how he thinks about the work that he’s doing? Like, is he interrupting the cycle of violence by doing this work? Or is there some way that he’s contributing to it? You know, or, or is there a deeper level of questioning than that?

Georgia Sparling

And yeah, Zachary never stopped being a pacifist, like both he and his mom. were quick to point that out.

Jon Watts

Yeah. Yeah. Well, I’m, so I’m looking forward to hearing more. You know, I’m particularly struck by Zachary’s reflections on what he’s planning to do while he’s in the military, like, does he see himself spiritually nurturing soldiers, and then just sending them back out on the battlefield? Or does he have a different agenda? You know, at the same time, it’s sort of like, who am I to judge? I mean, I know that the Spirit works in mysterious ways. And as Quakers we believe in continuing revelation, and our commitment to things like non violence, our I don’t know, they’re not set in stone. Quakers don’t have hard and fast rules about these things. But we do commit to deep listening and exploring these principles. And, and that’s why we call them testimonies.

Georgia Sparling

Yeah, and I think as Zachary talks about, you know, deep listening was a really important part of his coming to this decision. And, you know, I think that there is a lot of room for different interpretations of how the Peace Testimony is kind of manifested in each person’s life. Right. But yeah, so I think we will get into more of these complexities as we continue the second half of the episode. Great.

Jon Watts

I look forward to it. Let’s see what he says.

Georgia Sparling

Zachary’s family, his religious community, they’re flummoxed, and even in direct opposition to his joining the military as a chaplain. And he’s about to enter a world that is so foreign from everything he’s ever done.

Zachary Moon

I mean, there were so many things that will always be like remarkably strange about that experience because I was still this Quaker kid from Berkeley, California. You know, that I couldn’t get that out of my system, right. And I was plunged into this world that had dramatically different values and beliefs and practices and behaviors, ways of relating ways of organizing ways of doing things. And it was hostile. I mean, it was just the most uncomfortable, terrifying thing that I had been plunged into an it was exactly what I was supposed to be doing.

Georgia Sparling

But first, Zachary was off to boot camp. After five weeks of military life, he took a brief trip home to visit his family. On the plane ride, he immediately realized how much the military had already changed him.

Zachary Moon

There is hostility that is baked into the machinery of the military industrial complex, I mean, this institution exists to subjugate and control and destroy folks, I mean, that’s that’s that’s what the whole thing is about.

Georgia Sparling

Zachary is sitting in an aisle seat on a commercial airplane and he finds himself getting irrationally agitated just by the inefficiency of boarding an airplane. You may be thinking, yes, we’ve all been there. But then he sees another passenger walking down the aisle.

Zachary Moon

His shirt was untucked. His hygiene was all messed up. And he was walking slow and like he was, you know, and it was like he was the antithesis visually of what we had been working on putting into order for the last five weeks in boot camp, and I was filled out to the brim with disgust and revolt.

Georgia Sparling

Throughout boot camp, Zachary had had to shave twice a day to keep up with the Navy’s regulations for facial hair.

Zachary Moon

And that practice, right, the intensity of that and all of these other bits and pieces had gotten now in me, they were a part of my wiring, part of my embodiment, the way that I was living in the world, the way I was flying on this flight.

Georgia Sparling

And he’s sitting there thinking, I’m a noncombatant, I don’t know this guy, he isn’t my enemy.

Zachary Moon

And yet, there’s something in me that now knows that this person is other this person is divergent and therefore is problematic. It took my breath away. So I just realized, wow, as as old as my brain is as formed as my brain is, it could, you know, five weeks of living and breathing and doing everything else in that environment, can still take a hold of you and some of those kind of powerful ways.

Georgia Sparling

Recognizing the way that the military had already changed him was pretty startling. But despite what his mother had hoped, Zachary still knew he was in the right place. He emphasizes that there are some misconceptions about the people who serve in the military.

Zachary Moon

There are people of every shape and size, every belief system, every ideology, are serving in the military, because people are not serving in the military, in large part, because of ideological reasons, or political commitments, or I like this president, so now I’m going to join the military. The thing that really holds most of those people in common is that they are looking for ways to purposefully serve their community in their world. And those military recruiters showed up at their high school and told them, this was the way they would get to go to college, and that they would get to purposely serve their country. I mean, really big ideas are very compelling to 18 year olds. And until we fix some of the stuff in our country, that essentially doesn’t allow people to get access to college without having certain kinds of class privilege. This will continue to be exactly how this works.

Georgia Sparling

Zachary says that what many people don’t realize is that with the draft, there was more room for soldiers to criticize the military complex, like they had not voluntarily joined the military. But today,

Zachary Moon

everybody there psychologically thinks that they have volunteered and therefore they have asked for this. Because the ways in which I hear folks peace loving folks pacifist folks talk about the draft is though somehow what we’ve got right now is is is better. And it’s not better. And in fact, some of the consequence of it, it has actually been deeply problematic. What we have right now needs good chaplains even more because it needs chaplains who can often in small ways, create space for people to ventilate the horrific scenes that have happened to them and that they’re involved in.

Georgia Sparling

During his five years as a chaplain, Zachary said that he found the biggest need among soldiers was to have a place where they could speak truthfully about their experiences.

Zachary Moon

Sort of incredibly was I felt like I was being a really good Quaker. I was like putting my Quaker stuff to work all the time. Not in that I was a pacifist on the sidelines, you know, shaking my fist and holding my handmade sign saying war is wrong. But I was showing up, present available listening, right, being willing to understand the way that God moves in people’s lives in unexpected ways, right? That, that that God is truly present in our midst in ways that if we don’t quiet our own minds, we we might not even perceive all of the different ways that God is up in this space working in people’s lives like that was a big part of my chaplaincy work was just creating open spaces for people to show up and be human beings.

Georgia Sparling

As Zachary’s mom says, this is the way her son has been since he was young, stepping across the aisle being a hands on Peacemaker. She recalls a time when he participated in an anti war protests near President George Bush’s home in Texas. There were a bunch of counter demonstrations.

Laura Magnani

And all the peaceniks were, you know, were kind of huddled in their safe space and, and, and basically turning their backs on these other people. And Zach walked across the street and started talking to them, wanting to know where they were coming from, wanted to know, you know, and I mean, what’s the point of being a peacenik if you can’t, you know, reach out to people who just who disagree? Over and over again, I had seen him show up that way, you know, as a real peacemaker, and as somebody who didn’t, didn’t just talk to the people who agreed with them. And I could see from his witness that, you know, Quakers weren’t, didn’t take it far enough for him, you know, didn’t didn’t really do the hard work. In some ways. I mean, we just either we rested on our laurels a lot, I still think that or we didn’t, you know, when we’re we got comfortable, and we stayed there instead of really trying to open ourselves. So I think in that respect, that’s what I really learned from him. Was, was that peacemaking has to has to go on all the time.

Georgia Sparling

Zachary and Laura continue to have a strong loving relationship. I didn’t want to leave that part hanging. It’s been about 12 years since he enlisted. And looking back, Zachary admits that when he got this calling, he had a hard time expressing himself in the midst of such a big, messy, chaotic decision. He says that when they returned to this topic:

Zachary Moon

I’ve been able to be more clear and articulate for myself what was God doing right here. You know, I can be better at talking about that with her, I can be better at holding those questions with her. And with time, you know, she can think about it, she can see me doing it, she can face those fears and, and ask those hard questions and, and really do the faithful work to try to understand something that’s very hard to understand. And she’s been willing to do that, because she’s a deeply loving person. And and she feels that kind of way about me, right. So to me, I understand both her her reaction and ultimately her co journeying with me in this process to be a deep expression of her own faithfulness and her own courage.

Georgia Sparling

Today, Zachary is a professor of theology and psychology at Chicago Theological Seminary. He is part of a multiracial Protestant congregation. He says he sings hymns and listens to a sermon each week takes communion, but he still has deep ties to Quakerism.

Zachary Moon

There are still Quakers all over my life and friends and family and people who are very dear to me, colleagues. And and Quakerism is still my DNA. So discernment is still of the utmost importance to me, and, and our beliefs and our traditions and our history are still very much alike in my bloodstream that way.

Georgia Sparling

I want to leave you with one last thing that Zachary said to me during our interview as kind of some food for thought.

Zachary Moon

I think sometimes in different kinds of human communities, we think we have to find stuff that we all agree on. And that’s the sturdy stuff. You know, and Quakers have our own version of this, right? We we coat it with consensus, you know, well, there was consensus here, so that must be sturdy. And sometimes, unfortunately, that kind of becomes a least common denominator, kind of belonging, right, like, well, we couldn’t agree on the big thing, but we could agree on the small thing. So we’ve got the small thing. And I find myself less and less persuaded that that’s the strongest thing that human community can do. That actually finding ways to love in the midst of misunderstanding, of confusion, of chaos, of trouble, of difference and all that difference can generate in our community. Finding ways to hold on to each other and love each other and belong to each other in those moments is a much more powerful kind of way to be together. So rather than telling this as a story of how Zachary and Quakers broke up, you know, to me, this is more of a question of like, wow, how in the midst of trying to understand this really hard thing, a whole bunch of folks who are trying to figure out how to be faithful came apart at the seams. And that that wasn’t the end of the story. Not for me enough for them. That story is still being written, still being written today and will keep being written.

Georgia Sparling

Thanks so much for listening. And thank you to Zachary and Laura for coming on this episode. So what stands out to you about Zachary Moon’s story? Head over to our website to share your thoughts. That’s at QuakerPodcast.com. And while you’re there, you can also download a transcript from this episode, along with some discussion questions, and you can subscribe to the show. This episode was produced by me, Georgia Sparling, and also Jon watts. Jon also wrote the music for this episode. Thee Quaker Podcast is part of Thee Quaker Project, a brand new Quaker media organization with a focus on lifting up voices of spiritual courage and giving Quakers a platform and 21st century media. If you want to support our work, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter. We’re a brand new project and every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way. Thank you so much for listening. We make this show for you. And now that you’ve heard from us, here’s a little bit from one of our listeners. We recently asked for people to call in and tell us what the phrase conscientious objector means to them. Here’s one of the responses that we received:

Bernie Davis

This is Bernie Davis at Raleigh Friends Meeting in North Carolina. I initially came to recognize myself as a CO as a college student during the Vietnam War. Having not been raised a Quaker that was not an easy or automatic decision for me. I like to say I did not become a CO because I was a Quaker, I came to realize I was a Quaker because I was a CO. What being a CO meant to me at that time was that I could not directly participate in combat, take the life of another human being because I was ordered to do so by someone else. Thinking through my options, and choosing to apply for CO status on that basis seemed like a significant step at the time. In fact, it was the easy part. I’ve come to see refusing military service is only the tip of the iceberg of the true meaning of being a CO. Just as serving in a non combat role in the military leaves one participating in war.

There are countless ways our lives are connected to the causes of war, even though others are the direct combatants. Trying to live true to the broad implications of my CO beliefs has been a lifelong journey. Seeing myself as a CO to war has shaped my career in anthropology and peace studies, seeking to understand how the socio economic cultural structures are connected to the current prevalence of war, how these contrast with cultures that never experienced war, and how to promote culture change through non-violent creative approaches to conflict transformation. At the daily personal level, it constantly nags at other individual choices connected to all decisions about consumption and finance. As daunting and immense as this part of the iceberg is I’m provided hope in the human capacity to make these changes by the same spirit that guided me to the first step of becoming a CO. Thanks for your podcasts and for the work that you’re doing.

Georgia Sparling

Thanks so much for calling in, Bernie. We really appreciate hearing from our listeners. Now we’d love to hear from you. Give us a call and tell us what your first experience of Quaker worship was like. You can leave us a voicemail at 215-278-9411 That’s 215-278-9411 I know it’s tough, but please try to keep your answer to a minute and we might share your response on a future episode.

Recorded and edited by Georgia Sparling and Jon Watts

Original music and sound design by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Referenced in this episode:

- Zachary Moon is an author and professor who teaches at Chicago Theological Seminary.

Thanks for this expanded version of what I’ve heard Zachary share about before. I trust the leading he experienced and appreciate the work he is doing in the world. It isn’t my leading, but G-d doesn’t lead each of us in the same way.

I doff my hat to Zachary (yet another Quaker “sin”) for following the strong sense of purpose he felt and for exploring it/wrestling it through the confines of the Quaker structures he’d been given since infancy and childhood. May we all have such strong convictions toward peace (he’s a chaplain after all) and meaningful work serving other beings. How is serving as a chaplain in the military so opposed to his past participation in peace protests?

Can one not stay truth to their beliefs while also helping individuals in military roles find peace, a light or stillness in themselves and others? particularly those seeing active duty or being involved in decisions that will have negative costs along with perceived positive benefits? If Quakers can’t be chaplains in these settings, who do Quakers think should be serving as military chaplains?

I’ll add that there are so many expectations and judgements of others’ behaviors and beliefs that I’m hearing among Quakers, even from Jon Watts during the interlude on this one, that I am starting to roll my eyes anytime someone says Quakers don’t have a creed. Uncomfortable reactions to Zachary’s life choice sure seem to provide a lot of fodder for queries.

Oh yeah. “Quaker god” and “god god”? I hope that doesn’t just slip through the cracks for Quaker listeners.

Does this mean you cannot be Quaker if you are not a ‘Pacifist’?

Quakers embrace a stance of rejecting outward forms of violence. That does not mean that those whose vocation includes serving in the armed forces, where they are called upon to commit violence in the course of their service, are not needing of spiritual care. In fact, they may be among the most in need. Rejecting outward forms of violence is not the same as an absolute rejection of violence. It means that violence, such as military violence to prevent more harm, should be a last resort (as is also foundational to Just War Theory), and should be a “worst of bad options” that encourage us to strive for a world where that violence is not necessary. That suggests a powerful obligation to be an agent of constructive change with respect to the causes of conflict that potentially lead to violence. Please note, I am speaking for myself, here, and my own understanding and practice of the core principles of Quakerism.

Desmond Doss is the only pacifist to be awarded the Medal of Honor (7th Day Adventist). He never touched a gun. Multiple military honors and a Purple Heart. His calling was to be a Medic during WW2. He save 75 men during the battle at Hacksaw Ridge. There is a movie by that name also. God can do amazing things when we with with Him.

Oh (expletive). We are working within a system. It’s not about the individual (pharisee) purity of belief and belonging but a lived experience pushing back on the wounds of serving a state that plucks the young and abuses their humanitarian best intentions – including justifying violence and the military as a norm. His compassion leads. His compassion may not cover all he encountered, but he tried harder than the Quaker purists.

I was very interested in Zachary’s story, but I felt the podcast did not address some very important questions. I was drafted and spent two years in the Army, 1969-1971. I began going to Quaker meetings during this period. Every chaplain I talked to said basically the same thing: The war is right and just, and God wants you to fight in this war and do what you’re told. A chaplain is part of the military hierarchy, and is required to serve and obey that hierarchy. His or her job is to reassure people that they are doing the right thing by obeying orders. So, I wish the podcast had asked Zachary to discuss the inevitable conflicts that would come up between what the military wants him to do and what God yearns for him to do. How did he confront the military hierarchy? How did he deal with physical, sexual and emotional abuse perpetrated against young soldiers? How did he react to the extremely distorted version of history that the military propagates? And so on. Zachary signed up for a tough, conflictful position, and I would love to know how that all worked out. Finally, I would add that there are other ways to reach and help young soldiers. We need more civilian counselors/advocates working near military bases or on phone hotlines. Quaker House in Fayetteville NC near Fort Bragg is a great example of such an effort. I hope you can interview them for the podcast.