The Making Of Monopoly: How Quakers Shaped The World’s Most Popular Board Game

Monopoly is a game of wealth and property…or is there more to it? In this episode, we explore the twisty history of the world’s most popular board game, from its anti-capitalist origins to the Quakers who transformed the game into what it is today. This is a story of innovative women, big business, deceit, and the unknown legacy of Friends.

Subscribe so you don’t miss an episode!

What do you think about this little-known aspect of Quaker history? Tell us in the comments!

Download the transcript and discussion questions.

Discussion Question

- Friends in Atlantic City adapted Monopoly to fit their Quaker values. Is there a habit or practice in your life that could be tweaked to bring it more in line with your beliefs?

- Unable, Unwilling pokes fun at the Quaker nominating process while also putting a spotlight on unwieldy meeting commitments. Is this something that you’ve observed in your meeting? How might you or your meeting respond?

Georgia Sparling: Hi everyone – the show will start in just a second, but first I wanted to update you on the progress of our giving goal! As a reminder, we are a donor-supported nonprofit organization and we’ve got a goal to reach 100 monthly supporters by the end of June, which is very very soon. So many of you have responded already and we’re up to 91. Will you be one of the 8 people who signs up today to get up to that goal? You can give $5 a month, $10, $20 or more. It really makes a difference. So if you like what we’re doing, please consider partnering with us. Head over to QuakerPodcast.com. Click Support and sign up! Thank you for considering it. Here’s the show.

Max: This real estate agent actually helped Ruth determine what the exact land values were for those properties. So on the Monopoly, the Atlantic City version of the Monopoly, those are the land values back then. She also did some research in the records of the city hall, but it was tied to that Quaker principle of the fair price, the single price and it was also easier for children to play.

Various

Thee Quaker Podcast. Story, spirit, sound.

Georgia: I’m Georgia Sparling.

Jon: And I’m Jon Watts.

Georgia: Welcome back, Jon. Hannah assumed the co-host seat for our Kenya episodes. It’s good to have you back.

Jon: Thanks. It was good to know that you and Hannah were holding down the fort with the Kenya episodes while I was on the road filming for the pilot of our video project, which we’re launching next Spring. More on that soon, but yeah it’s good to be back.

Georgia: Thanks and thank you again to Hannah.

Jon: Absolutely.

Georgia: Now, today’s episode is very different from our past few. Today we are delving into the layered history of Monopoly.

Jon: Right! Boardwalk, Park Place, Marvin Gardens. Community chest. Passing go with your thimble. It’s an iconic game which a lot of us played as kids, and it actually has an unexpected history in which Quakers played a role! Georgia you’ve done a lot of research for this episode, do you want to fill us in? Are the rumors true? Did Quakers invent Monopoly?

Georgia: Well….not exactly, but it’s definitely the game it is today though because of a group of Quakers in Atlantic City, New Jersey of all places.

Jon: Right! That explains some of the street names. I’m sure you’ll get to that in the episode.

Georgia: Yeah, So Jon, you’re a board game enthusiast, what’s your experience with Monopoly?

Jon: Well it’s been a long time since I’ve played Monopoly but I did pull out a board to refresh my memory and played a quick round last night with my wife Jess and my mother-in-law Ann [people playing Monopoly]… I’d put this in the sort of “family game” category. It doesn’t take much strategy and the dice are really the primary engine of moving the game forward. But like all games, it’s still fun to move your piece around the board and grow your resources and try to win.

I’d also say Monopoly is unique in that it is just like so blatantly capitalist. Monopoly money is the closest to real thing of any game I’ve played, and the primary mechanic of the game–paying other players rent until you go bankrupt–is just like, brutally honest, right?

I mean just the name of the game, Monopoly, is kind of odd because you know, building a Monopoly is illegal and unethical, and it is also the goal of this game.

Georgia: Yeah well… interesting story about that. The game actually isn’t all about gaining wealth, or at least it wasn’t originally. It was more a condemnation of ruthless big business. There are a lot of layers to Monopoly’s origin story, which made this episode a fun one to research. The story has some twists and turns, some deception, and of course, some Quakers. Plus, we’ve got a little bonus story at the end sparked by my research into Quakers and games. So, should we get started on the story?

Jon: Alright, let’s hear it!

Georgia: So, Monopoly is about gaining property and wealth, but is the game as simple as that? We originally got the idea for this episode from our friend and Quaker historian Max Carter, so I called him to find out more about the origins of Monopoly and to learn how Friends became associated with the game.

Max: What was that game that became Monopoly? Well, you have to go back to Lizzie Magie, who lived in the late 1800s into the mid-1900s. Lizzie Magie was a progressive economist, woman, inventor, suffragist, feminist, and she was a disciple of the progressive economist Henry George. Henry George came up with a different kind of tax plan in the late 18th century that he thought was much more fair than the income tax. His single tax was a form of taxation on land valuation.

Georgia: Let’s say you owned a piece of farmland that 50 years ago was in the middle of nowhere. But now, the city has encroached with all the amenities that come with it — schools, paved roads, electricity — and what was once inexpensive farmland is now, through no fault of your own, worth 50 times what it was when it was simply a rural plot of land.

Max: So why shouldn’t the taxation value of such land go to the community rather than all the benefit go to the land owner who has little responsibility for the increase in value? So that was his basic theory.

So he proposed a single tax based on land valuation. And that became very popular among many progressives and among many Quakers because of their various Quaker testimonies of equality and simplicity and all that stuff.

Georgia: Several communities formed based on Henry George’s single tax theory, including a Quaker settlement in Fairhope, Alabama, and a Quaker-adjacent community in Arden, Delaware to which Lizzie Magie had ties.

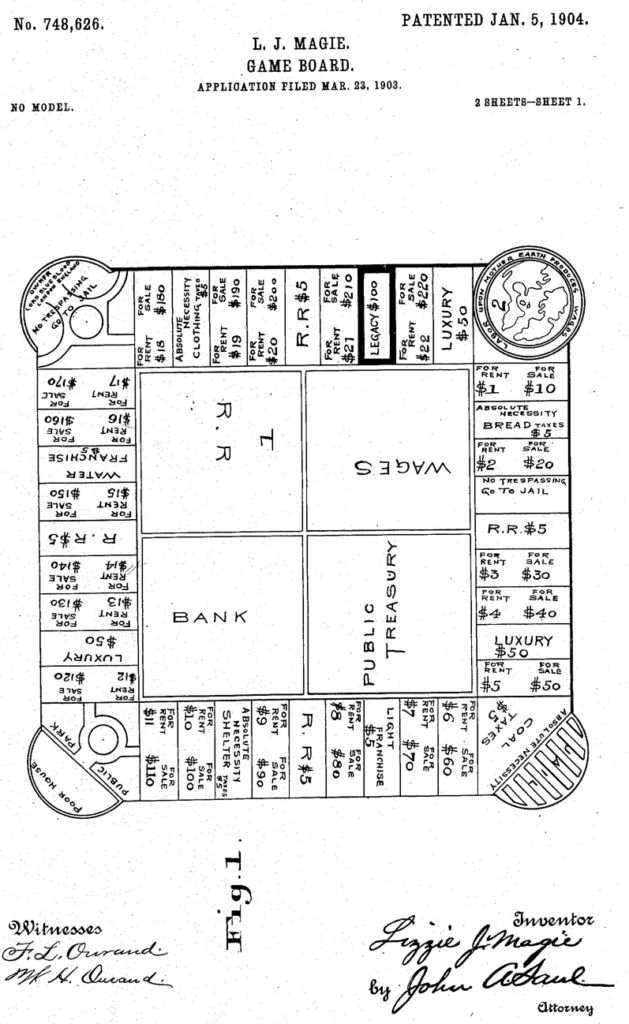

Max: Well, Lizzie Magie, not a Quaker, but a disciple of this economic principle, in the early 1900s developed a game to illustrate these principles called The Landlord’s Game. And it was played in order to show the terrible impact of monopolies on the economy. The rich get richer, the poor get poorer, and the whole landlord’s game that she had patented displayed that.

Georgia: The game’s board looks much like modern-day Monopoly, but the tiles are definitely more pointedly political. There’s a go to jail space owned by Lord Blueblood. And there are spaces dedicated to the absolute necessities — bread, shelter, coal, and clothing. Each comes with a $5 tax.

In her patent, filed in 1903, Lizzie states, “The object of the game is to obtain as much wealth or money as possible…” And that player becomes the winner.

Lizzie Magie had grown up during America’s Gilded Age, which saw the rise of industrialists like John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and Jay Gould — all of whom were known not only for their wealth but also their ruthless and unethical business practices.

The Landlord’s Game was a direct response to the wealth inequality that Lizzie saw in American society. So, the game was meant to be didactic and there were actually two ways to play it: One was the monopolist rules — basically every player for herself. And then there were the anti-monopolist rules: where every player benefitted when another gained wealth.

In true American fashion, the monopolist rules won out. And although Lizzie had patented the game, it began to be copied and adapted by people across the country, who would localize it to their regions and cities.

Eventually a version of the game makes its way to Atlantic City via Ruth Hoskins, a Quaker teacher who came east to work at the Atlantic City Friends School. At this point, the whole country is in the midst of the Great Depression.

Max: As the Quakers there at the Atlantic Friends School during the Depression got hold of this game, said, you know, we can’t afford to go to the movies, we can’t afford entertainment, you know, let’s play this game.

Georgia: They adapted the game to fit their Quaker values.

Max: The landlord’s game had an auctioning element to it. You put properties on at auction and that was counter to Quaker practice. Early Quaker business people pioneered the single price system that we know what this product is worth. We know what a fair price would be and that’s what we’ll charge rather than haggling with people and auctioning is a form of haggling.

Georgia: As Max says, that actually made the game less complicated and easier for kids to play. The Atlantic City Quakers also adapted the game to their city. The board that Ruth Hoskins had brought with her featured landmarks from Indianapolis, Indiana, but those names got changed to streets and neighborhoods in Atlantic City — a lot of them you’ll probably recognize if you grew up playing a standard U.S. version of Monopoly. And that has a lot to do with Cyril Harvey’s family.

Cyril Harvey: My father’s name was Cyril, just like mine, I was named for him, Cyril Harvey, and my mother’s name was Ruth, Ruth Thorpe Harvey.

Georgia: Cyril is a retired geologist and Guilford College professor, and Max put us in touch. Cyril is a Quaker in his mid-70s, and his mother Ruth basically designed the now-famous Monopoly board, which, of course, was based on the layout of Lizzie Magie’s original game. And yes, this is the second Ruth in our story, if you’re keeping count.

Cyril: The original board was painted by my mother and there were two or three other Quakers at the Friends school who were involved in this process.

Georgia: Ruth and a real estate agent friend actually pulled the tax records at City Hall to determine the land values of the properties, railroads, and utilities in Atlantic City and then Ruth painted the board on an oilcloth tablecloth, including spaces for the Boardwalk, Park Place, Marven Gardens.

Georgia: And was your mother artistic? Like, did she draw a lot?

Cyril: I wouldn’t say she drew a lot, but she was artistic. I remember when I was about five, we took a car trip to California, if you can believe that And I remember very distinctly that she had with her a box of pastel and chalk, and she used to stop and draw at landscapes.

Georgia: While Ruth Harvey’s original Monopoly board is lost to time, the Parker Brother’s version still bears hints of the family’s life.

Cyril: We didn’t have much money, so what we did is during the off season, we’d move to a fairly nice house, which we could get lower rents in. And then when the season came for the tourists, we had to move to a cheaper house. And so a lot of those actual cities are on, excuse me, streets are on the board today were the itinerary of this poor Quaker family moving back and forth summer and winter.

Georgia: Ruth also left her mark on the playing pieces.

Cyril: She had a thimble that she took out of her sewing kit and various other things that were just old model cars and things. But all the symbols were things that she found just lying around in the house and she picked them up and used them.

Georgia: The board made the rounds among Atlantic City Friends. And that’s how a certain man named Charles Darrow got ahold of the game, claimed it as his own, and basically obliterated the work of the women who created it. That’s after the break.

Ok, I have an exciting announcement from Thee Quaker Podcast Headquarters — we have won an award!!! You are listening right now to the recipients of the Associated Church Press’s Award of Excellence for a podcast or audio series! That’s right, we won for our very first season. I hope you won’t mind if we pat ourselves on the back for just a second because this award means so much to us — to be recognized for our first season is huge.

The award is granted to podcasts with deft storytelling and high production values, and that’s what we’ve set out to do from the very beginning. This award also comes with a big thanks to you, our listeners, who have cheered us. It is really great to receive this accolade, but really, we make these shows for you.

And it’s because of your generosity that we’re able to keep making new episodes, and your monthly support gives us the resources to make this show better and better! You know we have a big push to get 100 monthly supporters by the end of June. If you haven’t done it yet, please help us close in on that goal today by going to QuakerPodcast.com and clicking on support.

Welcome back. So Lizzie Magie’s Landlord’s Game had gained something of a following, resonating with Americans across the country, including among a group of Quakers in Atlantic City.

Enter Charles Darrow, an unemployed self-proclaimed “practical engineer” from Pennsylvania. During a trip to visit a Quaker friend in Atlantic City, he plays this board game, which from what I can tell was called Monopoly by then and not the Landlord’s Game.

Charles Darrow borrows the board, and the next thing you know, he’s claiming it is his own invention, and he’s selling it to Parker Brothers. He in changing it, he mostly just added in inaccuracies. Here’s Max.

Max: One of the pieces of evidence that the game had actually been from the folk who were playing in Atlantic City was two misspellings on the board. … Remember there are four railroads. One is the Short Line. There is no Short Line in New Jersey. There is a Shore Line. And Charles Darrow had misspelled it or misunderstood and put that one in his board game that he sold to Parker Brothers. The other was Marvin Gardens. M-A -R -V -I -N. Well, it was actually in the Atlantic City board game, a portmanteau of Margate City and Ventner City and the neighborhood that straddled those two outliers from Atlantic City was Marven Gardens, V -E -N.

Georgia: The board also hints at the city’s racial disparity, says Max.

Max: Ruth Harvey also put in a subtle statement about racism because what are the lowest priced properties — the ones through the African-American community. Baltic Avenue, Mediterranean Avenue. She knew that. One of the people they had hired to help in their house, a maid, lived on Baltic Avenue, an African-American woman, so she was making a statement that most people aren’t aware of.

Georgia: It’s unlikely Charles Darrow or Parker Brothers had a clue about that either.

And one more piece of evidence. There’s also a photo of the Harvey family at a dinner party where the game is clearly displayed. It’s dated a full three years before Parker Brothers printed Charles Darrow’s version.

But if Parker Brothers knew any of this, they didn’t care, and they published the game in 1935. It’s was a hit. The box even came with a little write up detailing Charles Darrow’s rags to riches story that led him to the creation of the game. Pure fiction.

What the Parker Brothers’ game lacked was mention of its true creator Lizzie Magie and the contributions of Ruth Harvey and the Quakers who created the Atlantic City board.

You know, it’s hard to hear the history without noting how ironic it is that a game created to denounce capitalism and promote the single tax system ended up being called Monopoly and featuring the streets of Atlantic City, the gambling capital of the East Coast.

Max: Where Quakers had a monopoly on the hotels. I mean, there’s the old joke, you know, Quakers came to America to do good and did well. And, you know, the Quakers, you know, had several of these luxury hotels there.

Georgia: According to one source I read, these Quaker hoteliers funded the Friends School where Cyril Harvey taught and they operated some of the institutions housed on the streets of Ruth Harvey’s Monopoly board.

Ok but back to Charles Darrow. In selling this game to Parker Brothers, he makes a killing on the royalties and never publicly acknowledges his deceit.

Ruth Harvey and her family get nothing. Lizzie Magie gets next to nothing.

When Lizzie finds out about the game, she contacts Parker Brothers and the press. An article published in Washington, D.C.’s The Evening Star, reports that Lizzie sold her patent to Parker Brothers for a mere $500 with no royalties. The article reads “If one counts lawyers, printers, and Patent Office fees used up in developing it, the game has cost her more than she made from it.” Yet, according to the article, Lizzie remained hopeful this iteration of her original game would introduce thousands to the single tax idea.

Unfortunately, that is not how things played out. Despite selling a second game to Parker Brothers, Lizzie did not have another hit and she died relatively unknown at the age of 81.

As for the Harvey family, Cyril says he only learned of the family’s Monopoly connection through his older sister Dorothy, who was eight years his senior and who remembered the family often playing the game on their mother’s oilcloth board.

Cyril: I never saw a game in our house. But my cousins lived next door. I used to go over there and play on their board.

Georgia: Although he can’t remember ever seeing his mother’s version of the game, he knows he must have at some point. Cyril recalls looking at his cousin’s manufactured board and registering that one of the illustrations was different from one in the back of his mind.

What happened to Ruth’s oilcloth board is unknown, and why Cyril’s parents didn’t mention the game to him is a mystery. Even so, they left their Quaker mark, whether or not most players ever know Monopoly’s origin story.

And if Monopoly isn’t Quaker enough for you, after this short musical interlude, I’m going to tell you about an intensely Quaker game.

Georgia: Ok, so Monopoly wasn’t really a Quaker game, though it had Quaker influences, and so I went in search of games that were created by Friends and I found one from the UK that I had to learn more about.

Sally: So my name is Sally Nicholls. I am a member of Liverpool Meeting in the northwest of the UK. I’ve been a Quaker all my life and I’m here today because I wrote a game called Unable, Unwilling along with my husband Tom.

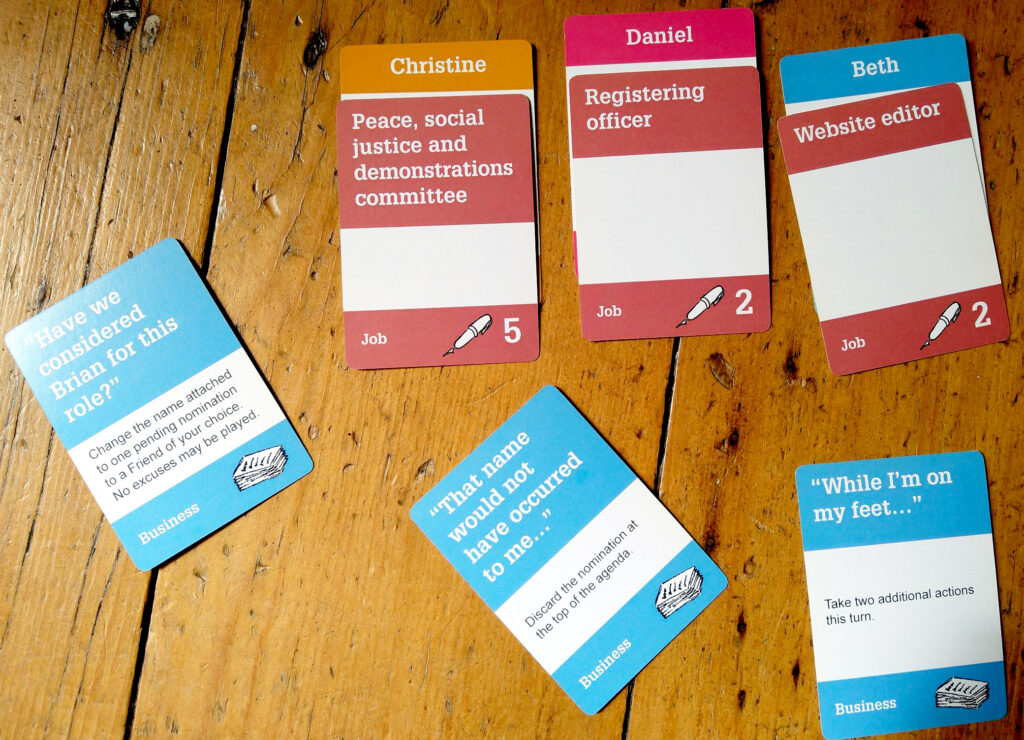

Georgia: That’s right. The game is called Unable, Unwilling. I just want to tell you up front that this game is sold out, but I think it’s really worth hearing about.

Sally: It’s a kind of satire of Quaker nominations procedure and the kind of chaos that is Quaker bureaucracy. So Quakers in the UK are all unprogrammed friends. We don’t have any ministers at all. Most meetings don’t have any paid positions. Certainly in the UK, and the impression I’m getting is that it’s also the same in America, Quakers are very good at saying yes to things and very bad at laying things down, which means that meetings get more and more kind of unwieldy and complicated and everyone’s like, we can’t possibly not have a representative to this committee, it’s really important even though there’s only four of us left in our meeting.

Georgia: Sally has had personal experience with the unwieldy and sometimes absurd nature of the Quaker committee nominating process.

Sally: I was a member of a meeting that very nearly appointed an assistant plant waterer. I was the member of a meeting that had a notice board committee, like not even a notice board individual, there was an entire committee whose job was to keep on top of the fairly small notice board in our meeting. And it was just kind of sucking up more and more energy that increasingly small and elderly meetings didn’t have.

Georgia: And out of this came the idea for Unable, Unwilling, a card game that centers on a fictional meeting called Little Snoring. Here’s the blurb on the packaging:

Sally: Little Snoring Quakers are in trouble. You can tell this is a UK game. Membership has declined so far that you, the players, are all that’s left. Unfortunately, Little Snoring still has over 40 nominated positions and they all need to be filled by tea time. Can you persuade your friends to nominate someone else or will you be the first to collapse some overwork, resign your membership and write an angry letter to The Friend? So The Friend is the UK Quaker magazine. And the idea is that you have a hand of cards and you have jobs and you’re trying to nominate other Friends to jobs.

And then you also have excuses and they’re quite comic ones. So there are, there are kind of general excuses that are things like, you know, have you considered the worthy friend to my left or, you know, I’m afraid I’m just too busy at the moment. And then there are kind of specific ones that go with specific jobs. So I think actually I quite like “war” was one of them.

It’s very tongue in cheek. It’s not taking it too seriously. But it’s also kind of trying to say, look, this is ridiculous. This is a real problem in a lot of meetings.

Georgia: Although, the game is meant to be lighthearted, there are winners and losers.

Sally: So bigger jobs have higher, higher point scores than others. And if you get to 15, a combined total of 15 points. So if your job gets to the top of the list and you’re appointed, that then sits in front of you as part of your kind of Quaker job portfolio.

And if your point score gets to 15, then you collapse from overwork, resign your membership and write an angry letter to The Friend. And then the idea is it’s sort of the last person standing who is the nominal winner, but they’re then the only person left in their meeting and, you know, 40 nominated posts that they have to fill by themselves. So it’s a sort of hollow victory.

Georgia: Originally, Sally had planned to handprint one version of the game and give it to Oliver as his going away present, but her husband Tom insisted they design it properly. Then, Oliver took it a step further.

Sally: He got wildly enthusiastic about the whole thing and said, you know we should sell this, and they printed 300 copies and we sold them at Britain Yearly Meeting.

Georgia: Unfortunately as I mentioned, Unable, Unwilling is sold out, though Sally said if interest really kicked up, they might be willing to do a reprint.

But there are other Quaker-created games out there. Jessica Metheringham, who actually married Oliver, runs a board game company called Dissent Games. According to Sally, the games have a Quaker ethos, including one called Disarm the Base in which people break into a military site to try to disarm it.

But maybe the market is ready for an infusion of Quaker games. Perhaps a Yearly Meeting-themed choose your own adventure-style game? Or a Role playing game where notable Quakers of old face off — Fox vs. Fell, Naylor vs. Nixon, Bonnie Raitt vs. Bayard Rustin?

The possibilities are endless.

Georgia: Thank you for listening and thank you to our guests, Max Carter, Cyril Harvey, and Sally Nicholls. If you want to learn more about Monopoly’s history, there is so much more to the story than we could get into here, but Mary Pilon’s book, The Monopolists does a deep dive into the topic. We’ve also got resources on our website if you want to learn more, including an NPR podcast that I got a lot out of.

Head to QuakerPodcast.com for links to those resources, and also for photos of the original Landlord’s Game and Cyril Harvey’s family posed with his mother’s oilcloth board.

This episode was written, recorded, and produced by me, Georgia Sparling. Jon Watts co-hosted this episode and also wrote and performed the music.

Thee Quaker Podcast is a part of Thee Quaker Project, a Quaker media organization whose focus is on lifting up voices of spiritual courage and giving Quakers a platform in 21st Century Media. If you want to partner with us, please consider becoming a monthly supporter. Every contribution expands our capacity to tell Quaker stories in a fresh way, and it makes this project more sustainable. Visit QuakerPodcast.com for more information, and now for Your Moment of Quakers Zen.

Your moment of Quaker Zen was read by Grace Gonglewski.

Grace Gonglewski: Phillip Gulley, 2024: We are a community, a collection of people who believe if you create a rich and meaningful and compassionate community, then those who participate in that community will soak up those virtues, will marinate in those virtues, and will become who we ought to be through osmosis, through the gradual assimilation of the highest ideals we can imagine. Quakerism is not a religion of the head; it is a religion of the heart.Georgia: Sign up for daily or weekly Quaker wisdom to accompany you on your spiritual path, just go to DailyQuaker.com. That’s DailyQuaker.com.

Recorded, written, and edited by Georgia Sparling. Co-hosted by Jon Watts.

Original music written and performed by Jon Watts (Listen to more of Jon’s music here.)

Additional music from the episode:

- “Ain’t We Got Fun,” Jones, Billy

- “Blues,” Frazier, C., Pittman, S. & Lomax, A

- “Welfare Blues”, C., Pittman, S. & Lomax, A

Mixed and mastered by Studio D.

Image by Freepik

Supported by listeners like you (thank you!!)

Referenced in this episode:

In the transcript, where Max is saying Ventnor, the transcriber heard and printed Vintner (perhaps due to his accent), negating his point of the MARgate-VENtnor portmanteau. You may want to change the text of the transcript.

Thank you! I’ll make that correction.

We recently play Unable Unwilling at Northern Yearly Meeting. One lucky member brought her copy. Please reprint/republish the game. I have Presbyterian friends who want to play too!

I’m also a presbyterian and, yes, I’d like to play Unable Unwilling!

The story in my family was that my great uncle and his wife, both Westtown School faculty, played the early version as it was being developed. Sure enough: https://share.google/JPgDCOjqseRTaiY7z

& a cross reference: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/the-landlords-game/